Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 22 Aug 2021

posted on 22 Aug 2021

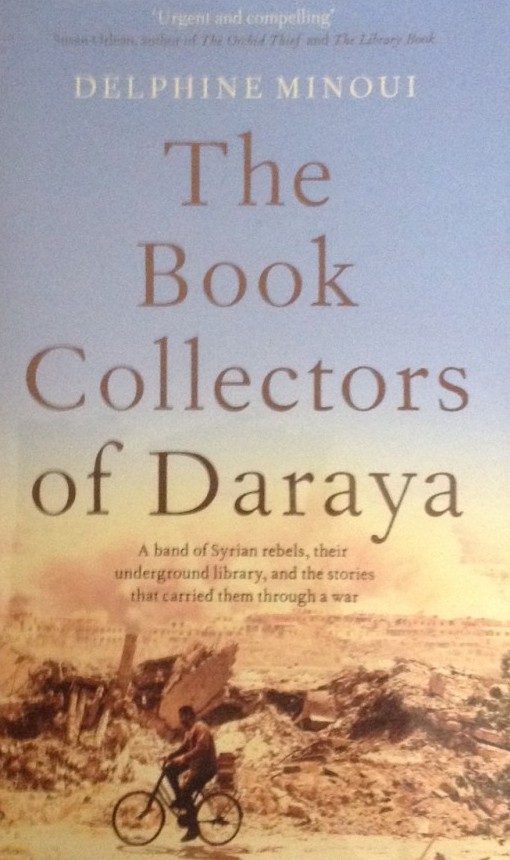

The Book Collectors of Daraya by Delphine Minoui

I still find it hard to really comprehend the way a series of small, peaceful but determined anti-government protests during 2011 in Damascus, Syria, became the seed-bed for what is now one of the longest, most destructive and bloody civil wars. With over half a million killed or missing and a country carved up into competing spheres of influence, it’s a human and political tragedy.

The decision of the Assad regime to remain in power through the use of force led to terrible scenes of the so-called ‘rebel’ areas being barrel-bombed and poisoned by chemical weapons until they either capitulated or had their whole towns destroyed. And when Daraya, just five miles from Damascus, was targeted as a rebel stronghold, the residents resisted and looked to the outside world for help. Very little of that help ever materialised.

When author and journalist, Delphine Minouri – partly based in Turkey and partly in France - came across a photograph posted on the ‘Humans of Syria’ Facebook site she was captivated. It showed two young men in Daraya under a caption that read ‘The secret library of Daraya’ and she was knew at that moment that she needed to know more. Clearly unable to travel to meet these young men she began a prolonged relationship via whatever social media she was able to use.

What emerges is the remarkable story of a group of men trapped in the besieged city who do everything in their power to save and collect books, organise them into a library and then make them available to all who want to read them. It’s an astonishing expression of belief in the universal and immediate importance of literature as an educational and civilising influence.

Mythili Rao, reviewing the book for The Guardian, describes the way the library is used in this way:

“The most popular titles range from self-help books by Tony Robbins and Stephen Covey to Arabic classics such as Kitāb al-’Ibar (The Book of Lessons) by the 14th-century Tunisian historian Ibn Khaldun, or the romantic verses of Syrian poet Nizar Qabbani. The library becomes a gathering place, too – for English lessons, for lectures and debates about democracy and revolution, and occasionally, for dancing and movie screenings. It’s a vital barricade for these young revolutionaries..”

But, of course, the basement library is not immune from the weapons of total destruction and, inevitably, it too succumbs eventually to the Government assaults. There are deaths and tragedies before an evacuation is brokered and the keepers of the secret library find their way to relative safety.

The bulletins from the library are compelling and tense – with plenty of emotional ups and downs as the revolution ebbs and flows around it. Minoui’s focus is not just on the library however – she is also intent on showing us the impact of watching a war unfold through the intimacy of social media. While it gives individuals a voice it also puts us at a distance from the reality of what it means to live under the bombardment of tons of high explosive. But when ‘war’ comes to France through the actions of ‘radical fundamentalists’, the reality of bombing stops being something happening in faraway lands and becomes a part of the everyday experience of the privileged West.

As Mythili Rao notes:

“And over time, the war begins to feel not so far away. In November 2015 Minoui finds herself frantically calling friends and family in Paris after learning of attacks at the Bataclan concert hall and Stade de France. She is shaken to realise that “violence has reached my home city”, the “invincible refuge, where I go to recharge between tough assignments covering wars, revolutions, and political crises. Suddenly, the lines are blurred.” Then, one morning in Istanbul, as Minoui and her four-year-old daughter Samarra are on their way to their weekly storytime session at the French Institute, a suicide bomber detonates a blast just outside the institute’s entrance. Minoui pulls Samarra inside, seeking refuge among books. The symmetry is uncanny.”

The book is translated from the French by Lara Vergnaud and at the end it also contains some brief pen-pictures of the key men who put together and maintained the library. These stories from conflict zones are important to document, not least because they are often the most graphic way of bringing the realities of war into the ghastly focus they need for us to understand the depressing reality of what is happening.

Terry Potter

August 2021