Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 16 Aug 2021

posted on 16 Aug 2021

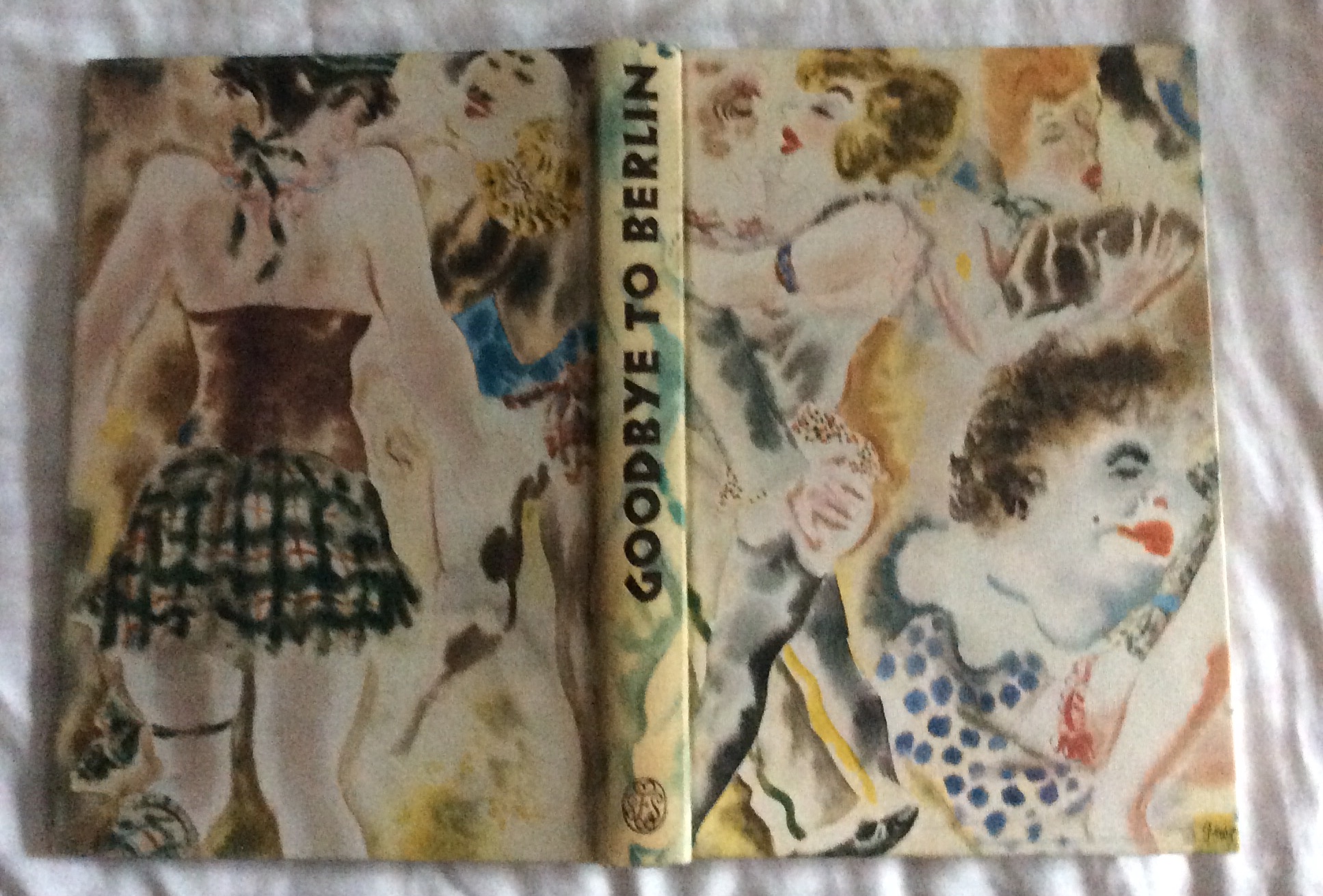

Goodbye to Berlin by Christopher Isherwood

Isherwood’s semi-autobiographical novel depicting Weimar Germany in the years prior to the outbreak of World War Two is perhaps best known for being the source material that produced two rather good films, I Am A Camera (1955) and Cabaret (1972). The author himself in a note at the beginning of the book tells us:

“The six pieces contained in this volume form a roughly continuous narrative. They are the only existing fragments of what was originally planned as a huge episodic novel of pre-Hitler Berlin. I had intended to call it The Lost .”

This much bigger plan had incorporated the now free-standing novel, Mr Norris Changes Trains, and has subsequently been re-coupled with Goodbye to Berlin to form The Berlin Stories. You can find a separate review of Mr Norris elsewhere on this site by following this link.

The book opens with the first of two sections called ‘A Berlin Diary’ and has the author looking out of the window of his apartment and ruminating on the Berlin he has come to. The second paragraph contains one of Isherwood’s most famous statements and which has become the starting point for many critical assessments of his work:

“I am a camera with the shutter open, quite passive, recording, not thinking. Recording the man shaving at the window opposite and the women in her kimono washing her hair. Some day, all this will be developed, carefully printed, fixed.”

It is at this point that we meet Isherwood’s larger than life landlady, Frau Schroeder and the mix of mainly women who are her other lodgers – Fraulein Mayr who is a vocal pro-Nazi and the more alluring and mysterious, Fraulein Kost.

Isherwood uses this opening section to orientate and locate the reader by also taking us on a tour of the Berlin nightclub scene and sketching out the atmosphere of decadence and decay.

Section two, Sally Bowles, is probably the most celebrated and best section and, in my view, could almost stand as a novella in its own right. Sally, young and full of life, is a marvellous creation and generally thought to be based on the 19 year old Jean Ross who Isherwood befriended and who he ‘helped’ procure an illegal abortion that almost killed her. Sally Bowles (a surname lifted from the novelist Paul Bowles) emerges from the book as a vivacious and fully-rounded character who has a further cameo appearance in the later novel Prater Violet.

Section Three moves to the Baltic resort setting of Ruegen in the summer of 1931 where Christopher is sharing a holiday home with Peter Wilkinson and Otto Nowak. The relationship between Peter and Otto is charged with sexual tension and Christopher finds himself trapped between the neurotic, middle class Englishman and the younger, working class Berliner. It’s a febrile triangle that comes to an end when Peter and Otto decide they can no longer live in a state of continuous bickering and argument and go back to their respective homes.

Parts four and five show Christopher moving in two very different environments – living as a lodger with Otto Nowak’s family in their overcrowded house and then contrasting that as he moves up the social ladder to spend time with upper-middle class Jewish family, the Landauers. Christopher is engaged to give English lessons to the rather prim and prissy daughter of the household, Natalia and there’s plenty of amusement generated when Natalia and Sally Bowles are brought together. But the most important relationship in this section is the one Christopher develops with Bernhard, Natalia’s cousin and manager of the Landauer’s department store.

This section is full of retrospective doom as we begin to understand the sort of dreadful fate that awaits the Jewish community. Bernhard’s mysterious sudden and unexplained death ends the section and leads to the final part, which like the opening, is called Berlin Diary. In this part Christopher reflects on his time in Berlin and concludes:

“Even now I can’t altogether believe that any of this has really happened”

In the end you are left with the clear impression that far from being, as he claims at the outset, a dispassionate recorder of his experiences, this book is in fact an intensely subjective and personal account of his experiences. And, I would suggest, all the better for that.

Terry Potter

August 2021