Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 05 Aug 2021

posted on 05 Aug 2021

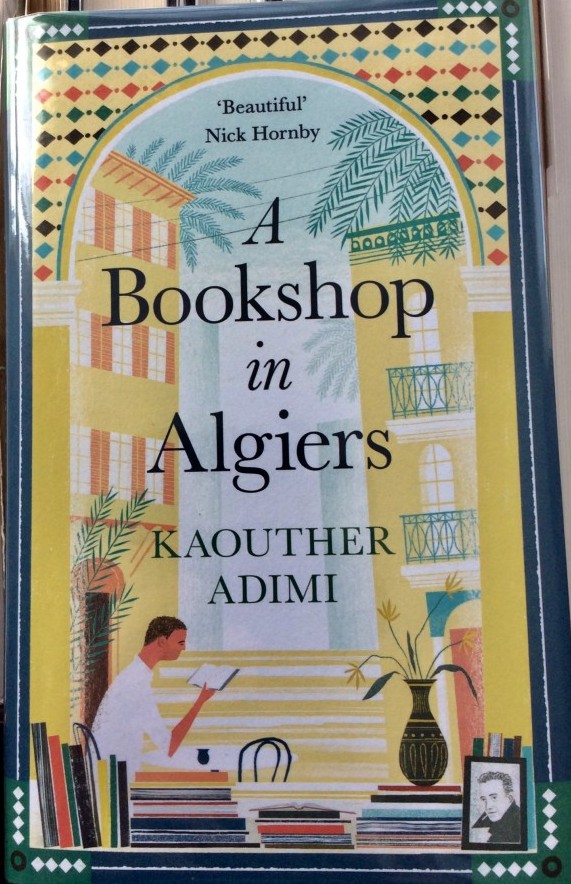

A Bookshop in Algiers by Kaouther Adimi

Edmond Charlot almost inadvertently became one of the heroes of 20th century book selling and publishing in both Paris and Algiers from the moment he established his famous – but tiny – shop, Les Vraies Richesses (True Riches), in 1936.

Charlot, who was born in Algiers in 1915, fell in love with books and found himself fascinated by the idea of publishing the literary voices of Algeria. Inevitably given its history of colonial occupation by the French, the world of books and publishing also became a political crucible that Charlot found himself involved in. The idea of Algerian independence and resistance to oppression landed him in jail for a period of time and, perversely, later in his career he would discover that the world of book publishing also has more than its fair share of vituperative internal politics and this would lead to him losing his precious publishing company.

But none of this seemed to daunt his belief in the power of literature and he will probably be most remembered as the man who first ‘discovered’ and published Albert Camus. So his is the kind of life that will probably result in someone producing the definitive biography at some point in the future – but this isn’t that book.

What Kaouther Adimi has produced here is a slim piece of fiction that imagines Charlot’s life story told predominantly through the mechanism of his (fictional) journal entries. Running in parallel with Charlot’s ‘diaries’ is a contemporary story of a young man, Ryad who has been hired to clear out what used to be Les Vraies Richesses, with the old bookshop being readied as the location for a new doughnut bakery. Although the shop had not been open for years (it had effectively been kept open by the government as an adjunct to the national library) Ryad discovers that memories of the book shop are rooted deep in the identity and psyche of the community.

Perhaps inevitably in a book of this kind, Ryad finds himself awakening to the possibilities of the books. As a result of this dawning epiphany he comes to understand why one of the former employees of the shop, Abdallah, finds it impossible to move on and why he ‘haunts’ the street outside wearing a shroud as a sort of cloak because, he explains, “the day God calls me, they’ll be able to bury me straight away.”

As Ryad is drawn into the community and comes to appreciate why this space is so very special, Abdallah’s words take on a greater and greater significance:

“Destroying a bookstore, you call that work?”

I’m not really in a position to judge these things but the general consensus of online commentary highly praises the work of Chris Andrews, the translator of Adimi’s original text and I’m happy to accept that judgement because I never felt any sense of clumsiness or disjunction in the flow of the text. A distinct sense of emotional directness is here too and this suggests to me that the translator had entirely understood and appreciated what the author herself felt about this story – and about Charlot and his bookshop.

As I mentioned earlier, this is a slim book that you can get through in a couple of lazy afternoons and for anyone who is addicted to book shops and love uncovering otherwise unknown stories of the bibliophile world, this is a must.

Terry Potter

August 2021