Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 14 Jul 2021

posted on 14 Jul 2021

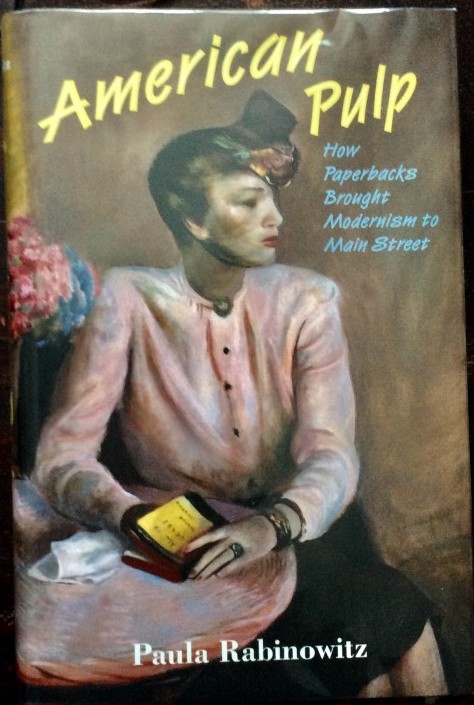

American Pulp by Paula Rabinowitz

What was the impact of the cheap paperback on American popular culture in the 1950s? This is the question that Paula Rabinowitz seeks to answer in her extensively researched, academic study of the subject that focuses largely on her own obsession for the output of the New American Library(NAL) – the US answer to the Penguin book revolution that Allan Lane had pioneered in the UK.

It’s important to say that Rabinowitz isn’t really interested in the kind of sensationalist stories of sex and violence that tends to get associated with the word ‘pulp’ but rather with what she sees as the ‘pulpification’ of more substantial and even classic literature. What she means by this is the publishing of well-regarded literature that was printed on scandalously cheap paper, bound with a dab of glue and expected to be disposable but given an alluring, vivid populist cover that was suggestive of the sensational and lurid.

“The mechanism of pulping a work entailed a process of redistribution or, more precisely, remediation: writings often created for an educated and elite audience took on new lives by being repackaged as cheap paperbacks.”

This, she claims, was essentially a Trojan Horse strategy to get good books into environments they would never have been in otherwise and appeal to readers who would never have gone within throwing distance of ‘literature’.

Just as Penguin books were seen as vital to the process of expanding the reach of high quality literature into environments that had never previously offered reading that went much beyond the comic or the scandal magazine, the NAL found a place in railway stations, coffee bars, newsagents and barber shops. An advertisement produced by the New American Library in 1951 quotes the admiring remarks of a ‘civic leader’ who captured this notion:

"There is real hope for a culture that makes it as easy to buy a book as it does a pack of cigarettes."

Her argument is that this new pulp product was responsible for helping to bring new ideas – Modernist ideas – to a population that might never have encountered them in any other way. She points to the fact that the cheapness of these books enabled them to be distributed in mass form as morale-boosting products to troops fighting abroad and that this would “help develop readers from even those with limited education.”

By focusing especially on the books of Richard Wright and Ann Petry, Rabinowitz makes the case that issues of race and inequality were introduced to people in a form they could access and engage with.

The books also offered a platform for other minority groups, providing this who were customarily thought of as ‘underground’ to have a legitimate presence. These pulps, she claims, was “one of the rare mass avenues open to depicting lesbian relationships.”

In all honesty, although the central premise was initially interesting, I found this book a bit of a slog by the end. I think the core idea really would have been happy in a book a hundred pages shorter and shorn of the often intrusive and irritating obscure academic terminology that seemed to be to be entirely unnecessary.

I don’t want what I’ve said above to sound like I regretted reading the book because I found much of it fascinating. Rabinwitz is clearly driven by a passion for her subject – she is a self-confessed pulp collecting addict – and I find that this often carries the reader through some of the harder slog.

The book is available in hard cover for under £20 – which isn’t expensive if you’ve got any sort of interest in this kind of bibliophilic study.

Terry Potter

July 2021