Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 11 Jul 2021

posted on 11 Jul 2021

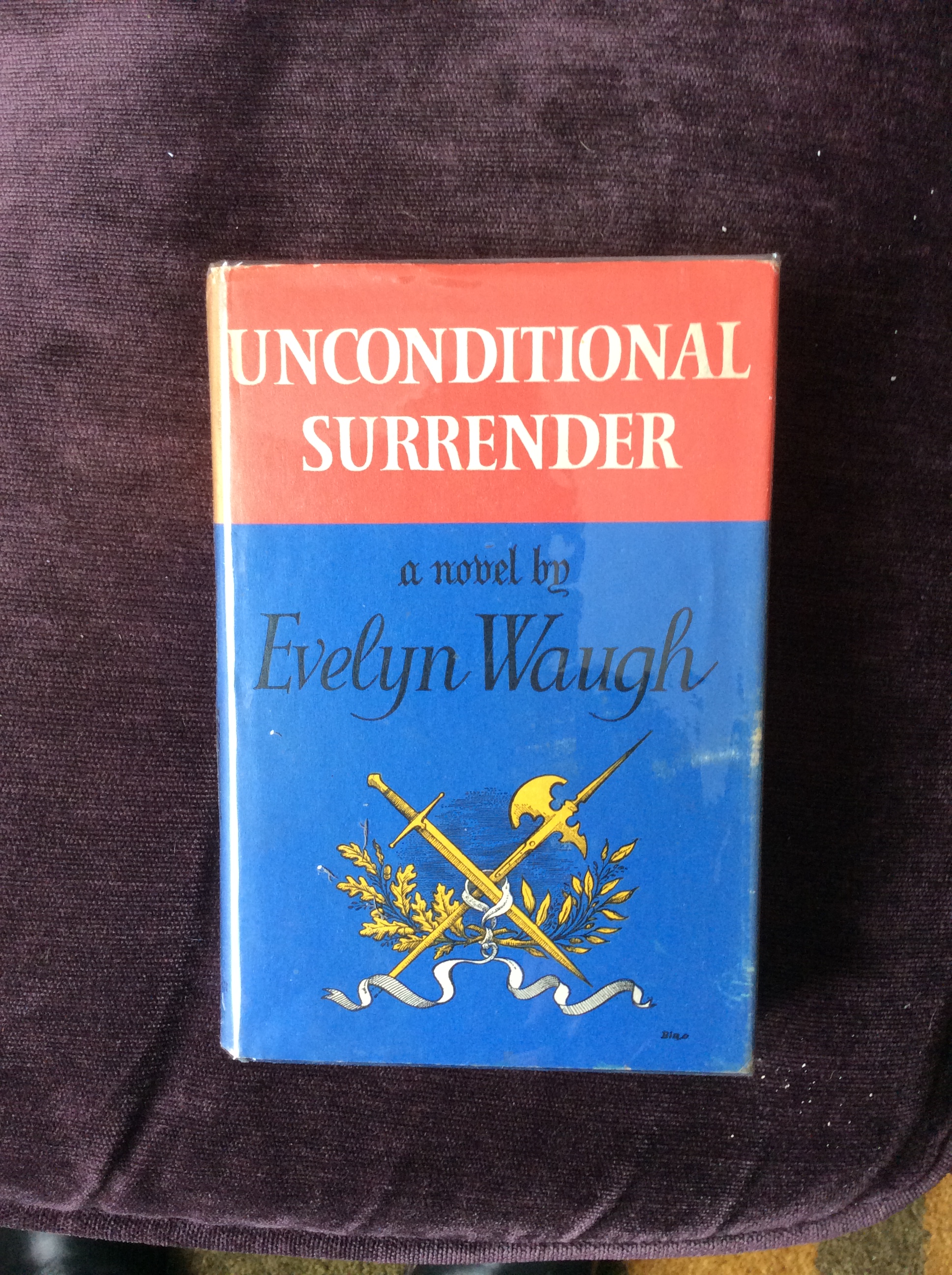

Unconditional Surrender by Evelyn Waugh

In Officers and Gentlemen, the second volume of Waugh’s Sword of Honour trilogy, we rejoined Guy Crouchback in black-out London following his ignominious discharge from the Halberdiers. In the third and final volume, Unconditional Surrender, Guy is again back in London and once more on the hunt for meaningful wartime employment. He still – just about – sees the defeat of fascism as an almost chivalric calling, one that his landed gentry ancestors would have understood and rallied to the flag for. On the other hand, he is realistic about his own declining physical powers and the absurdity and failure of at least some of the ‘actions’ that war has cast him as part of.

Unconditional Surrender was not published until 1961. Almost a decade separates its publication and that of the first volume, Men at Arms; and six years separates the publication of the second and third volumes. Indeed, in a foreword in the first edition Waugh makes plain that he originally anticipated there being only two volumes. It was only later, he says, that he fully recognised the need for a third volume in order to bring the sequence to a proper conclusion.

Perhaps this uncertainty on Waugh’s part accounts for the rather lacklustre opening to the book. For the first hundred pages or thereabouts not only do we see relatively little of Guy, we also see relatively little soldiering. Instead, Waugh focuses on filling out the roles of a number of peripheral characters. There is Ludovic, a mysterious officer whom Guy has previously been posted with. Is he a spy? Military intelligence? A communist? Homosexual? At various times Waugh suggests he may be all of these things but it turns out that he is a writer, a very bad one, obsessively compiling a gigantic book of aphorisms and pensées along the lines of Pascal. As a route to publication he is pursuing a cynical young magazine editor, Everard Spruce (perhaps based on Waugh’s friend, Cyril Connolly), whose left-leaning, avant-garde magazine, Survival, is temporarily in favour with the War Office because it helps counter Hitler’s condemnation of ‘decadent art’ and promotes the survival of democratic values – albeit with a marxist flavour, additionally useful, it is thought, with Britain’s Russian ally.

Waugh has good fun with these misfits and oddballs that increasingly have a part in Britain’s covert and propaganda operations: Sir Ralph Brompton, “a tall, grey civilian dandy…a figure of obsolescent light comedy rather than of total war”; a “Swahili witch-doctor…engaged to cast spells on the Nazi leaders”; the “small bands of experts in untroubled privacy [making] researches into fortifying drugs, invisible maps, noiseless explosives and other projects”.

A good deal of this undercover work takes place in offices hastily erected with plywood partitions in the Royal Victorian Institute, a museum temporarily requisitioned by the War Office. Here, on attachment to Special Service Forces Liaison Office, Guy has his own cubicle but spends most of his time watching the fascinating work of the ‘Beaches Dept’, where scale models of hundreds of miles of the coastline of occupied Europe are being constructed. The tone of Beaches Dept “was egalitarian in an antiquated, folky way distantly derived from the disciples of William Morris”.

In his foreword Waugh explains that in part his purpose in this third volume was to explain the background of characters he had previously neglected. The question isn’t whether this is funny or well done. It is both. The question is whether it really furnishes enough for a hundred pages or more. I found that the book didn’t really take off until Guy falls victim to an early computer – an Electronic Personnel Selector – which assigns him to parachute training. This is a sequence that has all the absurd knockabout farce and gallows humour of Guy’s commando training on Mugg in Officers and Gentlemen.

Perhaps the real purpose of roughly the first third of the book is to contrast with the deeply melancholy and tragic final third. I won’t spoil the plot for those who plan to read the trilogy; suffice it to say that war exhaustion, civilian casualties from the terrifying flying bomb raids that succeeded the Blitz, and the death of some of those closest to Guy make for very dark reading indeed.

The closing chapters of the book see Guy serve in ‘liberated’ Croatia where partisans are fighting the Nazis and each other in internecine struggles for post-war power. Guy adds further to his sense of personal shame by failing to save a group of a hundred or more Jewish refugees. In a crucial passage of the novel one of the Jewish refugees says to Guy:

“Is there any place that is free from evil? It is too simple to say that only the Nazis wanted war. These Communists wanted it too. It was the only way in which they could come to power. Many of my people wanted it, to be revenged on the Germans, to hasten the creation of the national state. It seems to me there was a will to war, a death wish, everywhere. Even good men thought their private honour would be satisfied by war. They could assert their manhood by killing and being killed. They would accept hardships in recompense for having been selfish and lazy. Danger justified privilege. I knew Italians – not very many perhaps – who felt this. Were there none in England?” Guy replies: “God forgive me. I was one of them.”

“For a chap who’s on his way home you don’t seem very cheerful,” Guy’s commanding officer observes as Guy prepares to leave Croatia. But then hurriedly changes the subject “for he had had many men through his hands who were returning to problems more acute than any they had faced on active service.”

But in fact, for Guy at least, the novel closes on a happier note. He is once again living in Italy in personal circumstances that at last bring him some happiness. Waugh gives the closing line of the novel to Guy’s supercilious nephew, the MP, Arthur Box-Bender: “‘Yes,’ said Box-Bender, not without a small, clear note of resentment, ‘things have turned out very conveniently for Guy.’”

This final volume required a bit of determination to finish, but I think that finally I do understand why the trilogy is considered by many to be Waugh’s masterpiece. Like all the best fiction, it is a fully imagined world in itself. I’m sure this isn’t the last time I shall read it.

Alun Severn

June 2021

Evelyn Waugh elsewhere on Letterpress

Men at Arms – Vol I of the Sword of Honour trilogy

Officers and Gentlemen – Vol II of the Sword of Honour trilogy

Rereading Brideshead Revisited by Evelyn Waugh

Put Out More Flags by Evelyn Waugh (June 2017)

Put Out More Flags by Evelyn Waugh (Dec 2015)

A Handful of Dust by Evelyn Waugh