Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 22 Apr 2021

posted on 22 Apr 2021

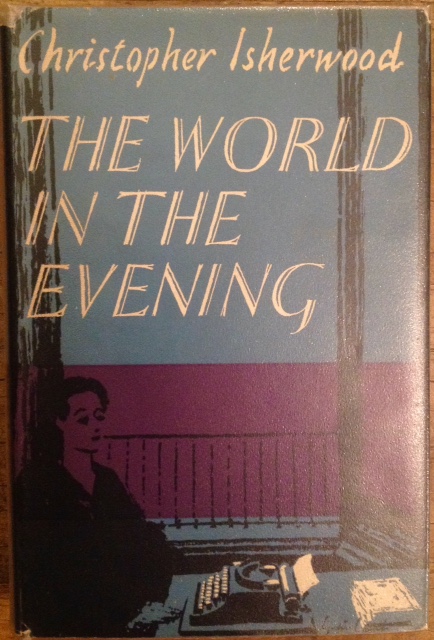

The World In The Evening by Christopher Isherwood

I’ve always felt a bit sorry for poor old Christopher Isherwood. His name always seems to get linked to, and live in the shadow of, W.H. Auden or he’s known as the man behind the original stories that inspired the film Cabaret – stories that those who loved the movie don’t actually get around to reading.

But actually Isherwood is something of a prose stylist and his 1950 novel The World In The Evening rather proves this point – it’s beautifully written and fearlessly (given the state of the law at this time) tackles issues of alternative male sexual identities: gay, heterosexual and bisexual.

Stephen Monk is independently rich, American but really a citizen of the world, and grotesquely unhappy when we join him as he narrates the collapse of his marriage to Jane, his second wife. Running from this cuckolding, he heads off to find sanctuary with his Quaker ‘aunt’ Sarah – a woman whose religious certainty both attracts and repels him. It’s the late 1930s and war has broken out in Europe and Aunt Sarah has also taken in a refugee from the Nazis, Gerda, who believes her husband has been captured and killed by Hitler’s mobs.

Stephen’s first wife, Elizabeth, was a famous author who was older than him and who died a few years before this story begins. However, she occupies the real living heart of the book because Stephen plans to edit and publish her letters – a task he started enthusiastically but has rather lost sight of following his marriage to Jane. When Stephen gets his thigh broken in an accident, his lengthy recuperation allows him to review Elizabeth’s correspondence and, through this device, Stephen narrates the history of his relationship to Elizabeth and, subsequently, to Jane. But along the way we also discover his barely suppressed bisexuality and his passionate but guilt-ridden relationship with Michael.

During his time lying in bed, remembering his life and his relationships, he is also brought into a closeness with his doctor, Charles, and the doctor’s partner. They are daringly living as an openly gay couple and he slowly develops a physically unconsummated intimacy. Isherwood uses Stephen’s discourses with Charles to explore an idea that can be seen in many ways to speak directly to Stephen’s situation – the concept of ‘camp’. Charles asks him if he knows what the term means and explains:

“You thought it meant a swishy little boy with peroxided hair, dressed in a picture hat and a feather boa, pretending to be Marlene Dietrich? Yes, in queer circles, they call that camping. It’s all very well in its place, but it’s an utterly debased form… What I mean by camp is something much more fundamental. You can call the other Low Camp, if you like; then what I’m talking about is High Camp. High Camp is the whole emotional basis of the ballet, for example, and of course of baroque art. You see, true High Camp always has an underlying seriousness. You can’t camp about something you don’t take seriously. You’re not making fun of it; you’re making fun out of it. You’re expressing what’s basically serious to you in terms of fun and artifice and elegance. Baroque art is largely camp about religion. The ballet is camp about love… Do you see at all what I’m getting at?”

And we begin to see how Stephen’s life is in many ways essentially camp and it’s his repressed homosexuality that is the key to his relationships with the women in his life.

When I first started reading this novel I thought it might not be one for me – and I had that thought a few times more as I read on. But actually I soon realised I had completely entered into the world Isherwood and his central character, Stephen had created for me. Soon I couldn’t think of putting it down until I had finished. This was testament to the author’s skill in creating prose as smooth as silk with an addictive edge.

Paper and hardback covers of this title can be found for only a few pounds – an investment that will pay some readers back many times over.

Terry Potter

April 2021