Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 19 Apr 2021

posted on 19 Apr 2021

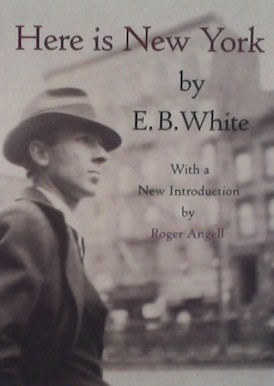

Here is New York: E.B. White’s most famous essay

E.B. White is most famous for his novels for children – Charlotte’s Web, Stuart Little and The Trumpet of the Swan – but he is also one of the twentieth century’s greatest essayists, contributing countless pieces to The New Yorker magazine. He died in 1985.

He is not a comic writer in the vein of Thurber (although he did collaborate with that writer on at least one book), but his quiet, homespun, deadpan, humane and elegant essays are essential Americana of a past age. He helped establish the tone of intellectualism and cosmopolitanism that became the trademark of The New Yorker while – in my view anyway – avoiding the smug self-satisfaction that sometimes mars the work of some other contributors.

White was most at home in rural Maine and many of his pieces explore the contrasts of rural versus urban life. His son-in-law has described White as an ‘inveterate non-traveller’ but in 1948 White was persuaded to contribute a piece to what was then a relatively new publication, Holiday magazine. Founded just a couple of years earlier in 1946, Holiday reflected a growing demand for quality writing on leisure travel, and by paying well and apparently offering lavish expense accounts it brought top-flight writers such as Flannery O’Connor, William Faulkner, VS Pritchett and Saul Bellow to its pages to write what we would now call long-form travel articles.

For Holiday magazine White wrote what has become not just one of his most cherished essays but in many startling ways his most prescient, Here is New York. In it he explores the tensions (racial and cultural discrimination, overcrowding, poverty) that should render urban life in New York an impossibility, and the tolerance and ‘inviolable truces’ that manage to render life in the city not just possible but essential and necessary for the many who have chosen it.

Written during the summer heat of 1948, White captures a disappearing old New York of speakeasies and diners, the demolished ‘El’ tracks, the neighbourhood ice-coal-and-wood cellars, and the thousands of neighbourhoods – often a handful of blocks, smaller than a rural village – that made up the patchwork of New York City. The essay captures a world that is only just beginning to recover from the Second World War and White identifies the UN headquarters between 42nd and 48th Streets – still three years from completion – as one of the most visible expressions of this.

White’s essay was published in Holiday magazine in 1948 and the following year was published in a slim volume of its own. In 1999, on the fiftieth anniversary of its first publication in book form and the hundredth anniversary of White’s birth, Here is New York was reissued in a facsimile edition by the Little Book Room, New York. The events of 9/11, still at that time a couple of years away, would forever change the way we read this pristine little essay.

The shocking prescience of the essay lies in the way that White at times seems to foresee the appalling tragedy of 9/11. He doesn’t, of course. He is writing against the more generalised paranoia and fear of a world recovering from war and the bleak prospects for humankind should it fail to avoid a third world war.

Nonetheless, when he writes the following it comes as a punch to the solar plexus:

‘The subtlest change in New York is something people don’t speak much about but that is in everyone’s mind. The city, for the first time in its long history, is destructible. A single flight of planes no bigger than a wedge of geese can quickly end this island fantasy, burn the towers, crumble the bridges, turn the underground passages into lethal chambers, cremate the millions.’

The very concentration of New York – of culture, of finance, of people, of buildings, of everything that as White points out make it not a national nor even a state capital but a ‘capital of the world’ – render it a priority target ‘in the mind of whatever perverted dreamer might loose the lightening…’

9/11 has without doubt given additional emotional heft and resonance to this essay but has not entirely hijacked its meaning. White’s affable, deadpan humour and humanity shine through, as does his enduring love of New York and his profound admiration for the writers and chroniclers and newspaper giants whose writings drew him there in the first place. (Joseph Mitchell’s essays of old New York, for example – now collected as Up in the Old Hotel – occupy a special place in White’s pantheon, but his list of heroes is a long one and an education in itself in American non-fiction writing and journalism.)

The opening and the ending of White’s essay are justly famous. ‘On any person who desires such queer prizes,’ White writes in the very first sentence, ‘New York will bestow the gift of loneliness and the gift of privacy.’ And in the final paragraph, writing of a modest and battered urban willow tree that he regards as a symbol of life-against-the-odds, he says, ‘Whenever I look at it nowadays, and feel the cold shadow of the planes, I think: “This must be saved, this particular thing, this very tree.” If it were to go, all would go – this city, this mischievous and marvellous monument which not to look upon would be like death.’

That curious but beautifully rhythmic inversion of the verb in the last few words is also justly acclaimed.

I think that Here is New York will be widely reread in this, the year that unbelievably marks the twentieth anniversary of 9/11. The Little Book Room’s elegant hardback can still be bought for under a tenner and secondhand copies can be found for coppers. Here is New York can also be found in the Harper-Collins paperback, The Essays of E.B. White (an excellent selection in the Perennial Classics series).

Alun Severn

April 2021

E.B. White elsewhere on Letterpress:

Separated by a common language: children’s books I didn’t grow up with