Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 28 Jan 2021

posted on 28 Jan 2021

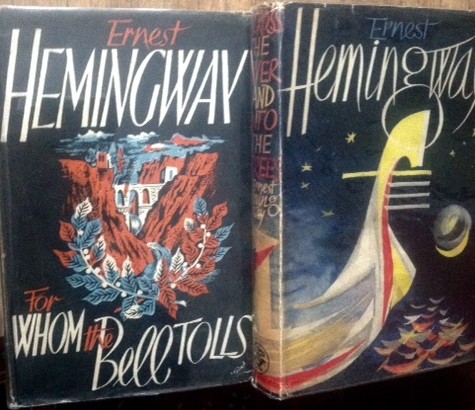

For Whom the Bell Tolls (with an afterword for Across The River and Into The Trees) by Ernest Hemingway

For Whom the Bell Tolls, Hemingway’s Spanish Civil War epic and his longest novel is widely considered to be his masterpiece. Recently, I picked up my old 1964 Penguin Modern Classics copy and read it – mainly because it has been many years since I last read any Hemingway and I wanted to see whether anything about the book surprised me.

Well, let me say that I was completely surprised, because it turned out to be a very different novel from the one I thought I knew. Clearly, if I had attempted to read it before I had never finished it.

Its hero – let us rather call him one of its heroes – is Robert Jordan, a young college lecturer from the United States who has joined the International Brigades to fight against fascism in Spain. Jordan is a dynamite specialist and the communist-controlled brigade he belongs to has sent him to enlist the support of local partisans whose help is needed to ensure the successful blowing-up of a strategically important bridge. Partisans – typically workers and peasants – are fighting a guerilla war against Franco’s fascists in the Sierra de Guadarrama mountains between Madrid and Segovia. Blowing the bridge will prevent further fascist troops being brought up to crush the ‘official’ attack that Republican forces in the area are launching against the fascists; it may also slow, perhaps even halt, the fascists’ advance on Segovia and allow troops loyal to democratic Spain to control it.

But Jordan’s orders are that the bridge must be blown simultaneously with the launching of the attack; it cannot be a hit-and-run sabotage attack and most of the partisans realise that consequently this means it is a mission they will be extremely unlikely to survive. If they are not killed in the fighting they’ll be hunted down by Spanish and German warplanes; and if they are unfortunate enough to be captured then death is equally certain but they’ll be tortured first. This tension between local guerilla fighters and ‘outsiders’ – international fighters whose orders may derive from foreign powers – is central to the plot.

I had mistakenly imagined the novel to be crammed with the complex minutiae of the Spanish Civil War. It isn’t, in fact. The novel takes place during the course of just three days and three nights and its primary concerns are the local partisans Jordan recruits, the unspoken sacrifice demanded of them, the preparations that must be made in order to blow the bridge, and Jordan’s tumultuous love affair with Maria, a young peasant woman brutally raped by fascist soldiers from whom the partisans rescued her.

The book is long but the demands it makes of the reader arise not from the complexity of its subject matter but from the fact that it is in some ways Hemingway’s most experimental and sophisticated novel. For while Hemingway’s characteristically terse, unadorned and sometimes graphic and brutal style is evident in For Whom the Bell Tolls, it takes second place to his audacious decision to render vast amounts of dialogue in a formal, archaic English that mimics the grammatical construction of Spanish and reads somewhat like Elizabethan speech.

Initially, I found this something of a shock but after a while the powerful polyphony of voices creates a unique sound-world and it is this that gives the novel much of its essential character and texture. After a while, it is difficult to imagine it done any other way. Hemingway also uses the idiomatic language he has created to furnish a rich tapestry of ambiguities, puns, darkly humorous asides and cross-purposes. The only current writer I have read who I think has explored similar techniques is Cormac McCarthy.

For Whom the Bell Tolls explores the themes that are familiar from the greatest war literature – kindness, cruelty, sacrifice; love and the testing of love; courage and fear; discipline and the ability to selflessly follow orders; immersion in the collective – the band, regiment, division – while also being able to exercise personal authority when one has that authority; and, what is perhaps Hemingway’s defining theme, grace under pressure.

It is a frankly exhausting and emotional read in which the complexity of the Spanish Civil War – its human and political cost, its self-sacrifice and courage as well as its barbarity and cruelty – is seen through the microcosm of a couple of small partisan bands, scarcely a dozen fighters all told, and the orders they accept and the sacrifice they make in order to blow up one otherwise insignificant bridge.

Is it Hemingway’s masterpiece? Personally, I think it is certainly his most ambitious novel, but I think it is at least fifty pages too long. At times one feels Hemingway has become bewitched by the sound-world he has created and a more stringent editing would have resulted in a clearer and tauter narrative. To my mind, his masterpieces remain the short stories, the posthumously published memoir, A Moveable Feast and some of the journalism collected in By-Line. At least, these are the works I have derived the greatest pleasure from over the years.

Nonetheless, For Whom the Bell Tolls is certainly an essential part of the Hemingway canon and without it one can have only a partial view of the writer. I’m not sure I shall read it a second time but I am profoundly glad to have read it once, properly and closely. There is much about it that is genuinely extraordinary, even if sticking with it requires a degree of perseverance.

I then read Across the River and into the Trees, the first fiction Hemingway published in the decade following For Whom the Bell Tolls. The 1940s were a troubled time for Hemingway. His literary heroes were starting to die, his own health was poor and both he and his wife Mary suffered a number of accidents and injuries. This is reflected in the ten-year gap in his fiction writing. When Across the River was published it was the first and only of his novels to receive negative reviews.

Sadly, these poor reviews were deserved. Across the River is about the final days of Colonel Richard Cantwell, a tough, beaten-up, opinionated and truly Hemingwayesque figure and his romance with a nineteen year-old Italian contessa called Renata. Cantwell, who is part of the US military security force occupying Trieste, is in Venice to shoot ducks with a local baron and to visit Renata. He is fifty, his powers are failing and he is suffering from what he knows is likely to be fatal heart disease. The flashbacks to his war years (both First and Second World Wars) and the incidental and descriptive writing about Venice are marvellous, but the pages and pages of dialogue with Renata are both tedious and frankly creepy. The novel is now a neglected one in the Hemingway canon but hardcore fans will still find it of interest and there is much to admire and enjoy. Certainly, it is not as disastrously poor as some contemporary opinion has suggested – the flame still flickers, sometimes brightly, but darkness approaches.

Alun Severn

January 2021