Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 04 Jan 2021

posted on 04 Jan 2021

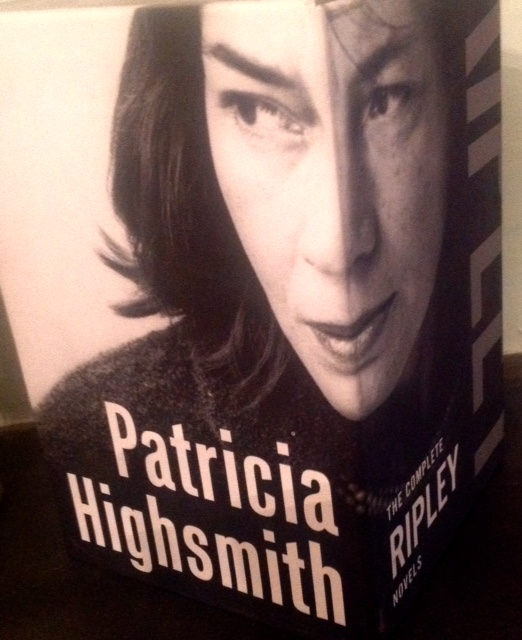

Patricia Highsmith’s Ripley Books

I have read so many disappointing books over recent weeks that a few days ago I was determined to find something dependable – light but not too light, a bit of excitement, engaging but not too demanding. What I think of as comfort reading, I suppose. I picked up something I haven’t read in years – one of Patricia Highsmith’s Ripley books.

Rather than start with the first (The Talented Mr. Ripley, 1955) – which I read again a few years back – I started with the third, Ripley’s Game (1974), which has long been my favourite.

The books in the series – some fans call it The Ripliad – are: The Talented Mr. Ripley (1955); Ripley Under Ground (1970); Ripley’s Game (1974); The Boy Who Followed Ripley (1980); and Ripley Under Water (1991).

The central character in all the books is Tom Ripley, one of Highsmith’s finest creations, a charming, debonair habitual criminal, sociopath and serial killer. He is amoral but perhaps not cruel – or at least, rarely intentionally so – and while he admires morality in others, most of his friends, including his wife Heloise, are as unscrupulous as he is, caring little where their money comes from as long as it enables them to live the kind of life they wish to become accustomed to. In the third book Ripley is happily set up in a lovely turreted country house in the village of Villeperce-sur-Seine, about forty miles from Paris.

Sadly, rereading – as so often seems the case – also reveals the weaknesses of a book or series of books and The Ripliad is no exception. Ripley’s Game stands out, I think, because it is focused and highly controlled, Highsmith’s tendency to pile plot twist on plot twist is held in check and consequently the tension mounts with ratchet-like precision. I find with others in the series that this isn’t always the case.

In Ripley’s charmingly unspoilt (and fictional) French village a not-very-prosperous Englishman, Jonathan Trevanny, runs a picture-framing shop, which Ripley, as an amateur painter (as well as deriving part of his income from an art forgery scam), has occasion to visit quite frequently. But Trevanny finds Ripley’s rather dubious, affectless charm easy to resist; in passing, at a birthday party the previous year, he also manages to say something that offends Ripley. It is this chance remark that makes Ripley think of the picture-framer when a small-time crime contact of Ripley’s, another American called Minot, is looking for someone to murder mafia enforcers who are moving in on a gambling club Minot has interests in. Ripley does lots of bits and pieces of ‘work’ for Minot but doesn't fancy this. In addition, he has discovered that Trevanny, as well as needing the cash, is suffering from leukemia and in any case may not have long to live. What follows is Ripley’s ‘game’.

Most if not all of the Ripley books have formed the basis of often excellent films, ranging from glossy star vehicles (Anthony Minghella’s The Talented Mr Ripley from 1999, beautifully photographed and starring Matt Damon, Gwyneth Paltrow and Jude Law), to stylish art-house thrillers (Ripley’s Game from 2002, directed by Liliana Cavani and starring a brilliantly cast John Malkovich as Ripley), to atmospheric European neo-noir masterpieces (Wim Wenders’ Der Amerikanische Freund from 1977). As is sometimes the case, these films work wonderfully because they use the very best that Highsmith’s source material offers while excising and streamlining the plots.

And what Highsmith offers in quantity is brilliant, sinister atmosphere, wonderful detail and incidental writing and of course terrific locations. In fact, these are the qualities I really read her for rather than the plots.

In Ripley’s Game, for example, his house, Belle Ombre (beautiful shade or shadow), is almost as much a character as the people are. The local streets and cafés and bars, with their zinc counters and odours of marc and rough red wine and French tobacco, fill the pages. Ripley’s lithe, desirable and amoral wife Heloise – clearly a character Highsmith had considerable pleasure in imagining – is an almost physical presence. By contrast, but accurately, Ripley is a sort of detailed non-presence, a space that can be filled by anyone – himself included – with an imagination. He wants to be a cultivated, civilised character, but to a great degree it is all show. His painting, his love of good food and wine, his highly selective reading (Goethe, expensive art books, classics), his eighteenth century harpsichord and love of Bach, his insatiable desire for certain pieces of classical music – it is the very personality type of a high-functioning narcissistic sociopath. It is display. It is a man playing a part before his own interior audience. Highsmith knew exactly what she was doing.

Over the sixty years or so since the first Ripley book appeared many have observed that despite all this, Ripley is likeable, and it is true – and especially so in Ripley’s Game.

After reading Ripley’s Game I moved backwards and read the second in the series, Ripley Under Ground (1970). Again, there is rich descriptive and incidental writing and some marvellous set pieces, but I found the last thirty or forty pages sagging under the weight of endless plot twists and reversals. From memory, I think I may have found the same problem with the fourth in the series, The Boy Who Followed Ripley, and I don't think I have ever read the fifth and final book, Ripley Under Water.

I’m going to have a bit of a break from Ripley and read something else, but I shall try books four and five again in the near future and see how I get on. What I don't want to do is dilute the pleasures of Ripley’s Game, which I am now more than ever convinced is the best of the batch and probably one of Highsmith’s best books. I shall also reread Andrew Wilson’s excellent 2003 biography of Highsmith, fittingly called Beautiful Shadow.

Alun Severn

January 2021

Patricia Highsmith elsewhere on Letterpress:

Strangers on a Train by Patricia Highsmith