Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 21 Aug 2020

posted on 21 Aug 2020

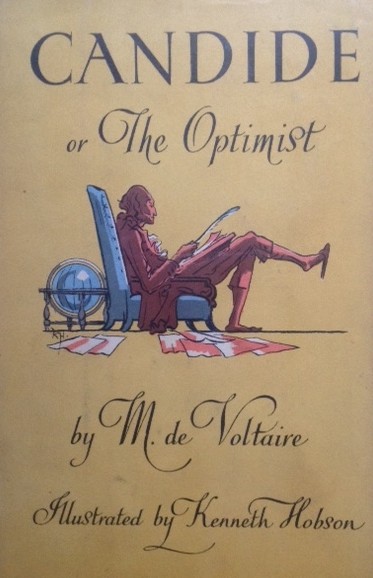

Candide, or The Optimist by Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (1694 – 1778) took the pen-name Voltaire and became one of the leading commentators and satirists of his age. And what an age it was. The ferment of new ideas and iconoclastic thinking in Western Europe that characterised the end of the 17th and first half of the 18th centuries has attracted different names – including The Enlightenment and The Age of Reason. Although such labels can often be misleading and unhelpful, what they do is to try and capture, in a single phrase, the changes taking place in the wider intellectual environment. These changes embraced thinking across a huge range of subjects - the nature of the public, literary, philosophical, political and religious debates. At the heart of the new thinking was an emerging belief in the scientific method which would in turn lead to the growing belief that, as Alexander Pope put it, ‘the proper study of mankind is man’. This signalled a new humanism and a breaking of the stranglehold of dogmatic religious teaching. Writers like Voltaire were prepared to question the existence of God and, for those reluctant to embrace atheism, kicked off a new investigation into the nature of God.

Probably written in or around 1758, Candide satirises the writings of Leibnitz, who in his work, ‘Theodicee’ had sought to demonstrate that not only did God exist but that He had created the ‘best of all possible worlds.’ Leibnitz’s publication articulated a strand of optimistic philosophy that Voltaire could not let pass without comment. The belief that we were living in the best of all possible worlds had been cruelly exposed as unwarranted complacency in 1755 by the worst contemporary natural disaster that Europe had experienced when the Lisbon earthquake destroyed one of Europe’s principle cities and killed thousands. How exactly would this fit into God’s plan for the perfect world? Natural disasters are one issue but, as dissenting philosophers and thinkers pointed out, there are also many more every day minor tragedies experienced in the wretched lives lived by so many citizens in Europe – lives so miserable they would lead in due course to a wave of revolutionary insurrection. Was all this part of God’s ‘best of all possible worlds’?

Candide is in fact a pretty direct, even unsubtle, satire and almost Swiftian in its aims and structure. It takes the form of a picaresque adventure in which the hero undertakes a rambling journey through life, learning lessons about the unfairness and cruelty of the world. I certainly can’t do better than Julian Barnes (writing in the Guardian in 2011) in summarising the action:

“ It is not – does not try to be – a realistic novel on the level of plot: the narrative proceeds by means of incredible coincidences and enormous reversals of fortune; characters are left for dead, and then improbably revived a few pages later when the argument requires their recall. In this genre, the participants are even more subject than usual to the whims of the puppeteer-novelist, who requires them to be here to demonstrate this, and there to demonstrate that. They have opinions, and represent philosophical or practical responses to life's fortunes and misfortunes; but have little textured interiority. Candide, the innocent of all innocents, is a kind of pilgrim who makes a kind of progress as a result of the catalogue of calamities inflicted upon him by the author; but those around him, from the deluded Pangloss to the disabused Martin to the doggedly practical Cacambo, remain as they are when first presented. Pangloss, despite relentless evidence against his Leibnitzian view that the world demonstrates a "pre-established harmony", is defiantly foolish to the end: "I have always abided by my first opinion . . . for, after all, I am a philosopher; and it would not become me to retract my sentiments."

For me, Voltaire’s dyspeptic and often astonishingly violent satire is a document for all ages and not just his own. He stands beside Swift in expressing his disgust for humanity and the stupidity and cupidity of the species. But this isn’t a critique based on misanthropic tendencies but in a deep-seated disappointment over the behaviour of people who are capable of so much and yet behave so badly.

There are so many wonderful editions of Candide available to buy in a range of different editions. If this book isn’t already part of your library then it’s certainly time to add it to your shelves.

Terry Potter

August 2020