Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 18 Aug 2020

posted on 18 Aug 2020

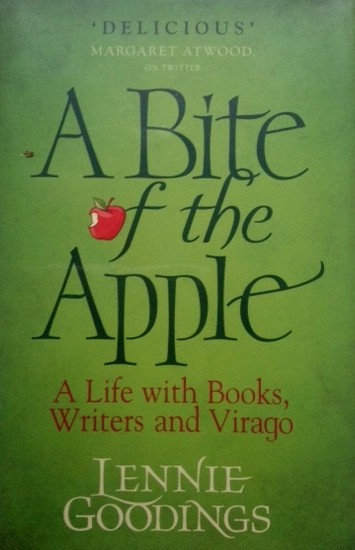

A Bite of the Apple: a life with books, writers and Virago by Lennie Goodings

I can’t quite remember where exactly in the book it is but there’s a passage that says something to the effect that the Virago Classics series of trade paperbacks radically changed the way many bookshelves looked - their distinctive green spines and a format that was slightly larger than other standard paperbacks were unmissable. For me and so many of my contemporaries and close friends this was absolutely true. The decision to reprint ‘lost’, ‘forgotten’ or scandalously neglected works by women authors was a stroke of genius – not just because it brought so many writers back to life but from a marketing perspective it was a giant step. Walking up to a bookshelf that had a row of Virago paperbacks on them said something about the owner – where they stood culturally and politically. The ownership of books by Virago was a statement about your awareness or commitment to the ideas of feminism and equality that were so visceral in the politics of the early 80s.

Canadian, Lennie Goodings came to London in the late 70s fired with the longing to establish herself in the world of books and publishing and found herself being eccentrically interviewed by the redoubtable Carmen Callil who, at the time, was the moving spirit and iron fist behind Virago books. A job followed and, unknown to her, a long and influential career in Virago and the women’s equality movement would follow. This memoir tells the story of both Goodings’ career and Virago as a publishing house and it does that in some detail. Bidisha, reviewing the book for The Guardian puts it this way:

‘Putting women’s lives, women’s stories and women’s words back into history requires work. A Bite of the Apple is about the women who did this work from the 1970s onwards, a time of huge activism around race, class and sex, when “women wanted a voice, women wanted to understand their history, women wanted to see themselves on the page… women wanted their share”’.

And, for those who want to understand the development of Virago, follow the debates around feminism and publishing and meet some of the extraordinary staff and the writers they served, this book will fascinate from beginning to end.

But I have to be honest and say that while acknowledging all these strengths, I thought it had one significant Achilles heel – it’s a bit dull. How can that be? With all that great material being presented by someone with a unique and privileged insider perspective it must surely be almost impossible to make it just a bit dull?

I think the problem lies in the writing. Being a great publisher doesn’t mean you’re also a great writer and Goodings, thorough as she is, just can’t make the text lift off and sing in the way it could. She has a tendency towards making lists – especially lists of authors – and teeters on the edge of gushing over the writers Virago published. The overall effect of that is to make the book feel a touch anodyne and in need of an injection of indiscretion or vitriol to pep it up. When things go wrong Goodings comes over as pained and disappointed rather than angry and the book needs some anger.

As a man who was, by necessity, always on the edges of the women’s movement even I was aware that there were vituperative arguments over how the different factions within the movement wanted the cause to develop. These fallings-out over tactics and objectives that seem to fragment all radical movements, could be divisive and hurtful and Virago itself, as an institution, was the target of attacks from parts of the women’s movement that felt they weren’t radical enough. These arguments clearly had a deep impact on the young Goodings and it almost feels that she writes this book still looking over her shoulder at these potential critics. She takes real pains to justify why Virago wasn’t a workers co-operative and why being market-driven and financed by big corporates was the legitimate way to go despite accusations of collaboration with capitalism. It leaves you with the feeling that maybe she protests too much and that the need to justify both Virago and herself takes precedence over all else.

But I don’t want to make this sound like a bad book because it really isn’t – there’s plenty here to interest and to like. But I can’t escape the feeling that it could have been so much better.

Terry Potter

August 2020