Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 10 Dec 2019

posted on 10 Dec 2019

The Life of Birds by Quentin Blake

Writing about the rich tradition of fairy tales that have used animals as surrogates for human beings in order to comment on our folly, pride and general beastliness, Marina Warner, the renowned scholar of childhood myths, has written:

“ The anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss commented that animals were "bons à penser" (good to think with), and fairytales speak through beasts to explore common experiences – fear of sexual intimacy, terror and violence and injustice, struggles for survival. A tradition of articulate, anthropomorphised creatures of every kind is as old as literature itself: animal fables and beast fairytales are found in ancient Egypt and Greece and India, and the legendary Aesop of the classics has his storytelling counterparts all over the world, who use crows and ants, lions and monkeys, ravens and donkeys to satirise the follies and vices of human beings and display along the way the effervescent cunning and high spirits of the fairytale genre.”

She goes on to note that the use of particular animals as representative of specific aspects of human behaviour is also a feature of this tradition but whatever the animal that is featured by the writer or artist, “the outer form conceals the inner man”. This is clearly a maxim that has been taken to heart by master illustrator, Quentin Blake in his book The Life of Birds – a book that has very little to do with birds and a lot to do with people.

Blake says of his fascination for birds as subjects for human observation:

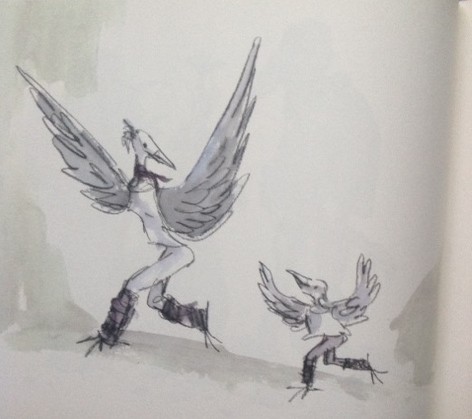

“I have always liked drawing birds. I can't quite explain why but it may be because like us, they are on two legs and have expressive gestures. It's a way of commenting on the people we see around us without actually drawing individuals.”

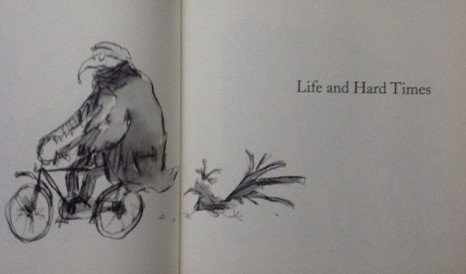

This collection, in a generous large format landscape edition, allows Blake free rein when it comes to highlighting human pretence and behaviour. Blake’s intention is clearly to produce a folio of drawings that when taken together amount to a (gentle) satire on all of us. By doing this he is joining a long list of those who use the animal fable to highlight human foibles – Aesop, La Fontaine, Jonathan Swift, Edward Lear and even George Orwell.

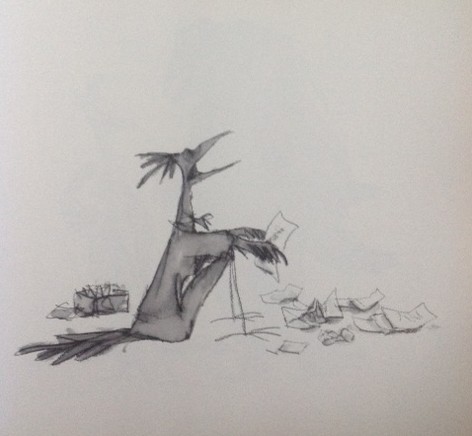

This is a book entirely without words and it relies on the broad brush-strokes of the drawings to carry depth and meaning. Everyone is likely to have their own personal favourites and it might be invidious to single out what I might consider the stronger or the weaker. However, there are some themes that emerge rather triumphantly from the collection and these deserve mention.

He’s very good at pricking the bubble of the puffed up and the self-important. Quite how you make a bird look like its spent way too much time with a bottle the best port and far too much rich food is way beyond me but Blake manages it with a deft brush stroke here and a drop of colour there. He also captures age well and especially cross-generational conflict where the young and old are in their habitual state of getting up each other’s noses.

Blake is also very good with minimalist backdrops and he’s clearly not afraid of the white paper – he’ll leave a bird suspended in the white space without any clutter if that feels like the place it needs to be.

A sense of freedom and glee pervades the book and it seems obvious to me that this is Quentin Blake let off the hook and allowed to spend a bit of time on a favourite hobby-horse. And because of that it’s a delight for the reader too: you can spend as much time as you want with each drawing and construct whatever back story you want for each character.

The book is a hardback but it can be purchased for laughably low prices on the second-hand market. This is affordable artwork at your fingertips – what’s there not to like about that?

Terry Potter

December 2019

(Click on any image to view them in a slide show format)