Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 26 Aug 2019

posted on 26 Aug 2019

Rereading Gulag literature

First published in 1962, Solzhenitsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich (which is reviewed on Letterpress here) is probably the single best known title in the literature of the Soviet-era gulag system. It has earned a rightful place as a record of human endurance and of physical, moral, spiritual and intellectual courage. That such testimonies from Stalin’s labour camps were ever written in the first place is truly remarkable.

But this is even truer when we consider the literature that came out of Kolyma – the most brutal, the most extreme and the most deadly locality in the entirety of the gulag system. Kolyma denotes the network of labour camps and mines in the furthest north-east corner of Siberia – eight time zones and 5,600km from Moscow. Kolyma was also the heart of Russia’s gold mining operations and every scrap of gold hacked out of the concrete-hard permafrost represented arms and ammunition with which to kill Nazis, Stalin said. Thus no labour was “worthier” than Kolyma’s mines and no labour more readily justified the expenditure of human life. The journey alone to Kolyma could be deadly and tens of thousands died during the transports to Stalin’s most distant labour camps.

It is significant, then, that two of the most extraordinary books documenting Stalin-era hard labour specifically concern Kolyma.

The first is Kolyma Tales, a collection of short stories by the dissident Varlam Shalamov, a member of the Left-Opposition who was arrested and charged with Trotskyism and who served almost twenty years of hard labour, seventeen of these in Kolyma. Solzhenitsyn called Shalamov the poet of Kolyma and regarded him as the superior writer. Shalamov’s imprisonment, Solzhenitsyn said, “was more bitter and longer than mine, and I say with respect that it fell to him, not to me, to touch that bottom of brutalisation and despair to which the whole of camp life dragged us”. Shalamov in fact had little time for Solzhenitsyn – their political views were very different – and resented Solzhenitsyn’s eventual fame. He also turned down Solzhenitsyn’s request that he collaborate on the latter’s gargantuan study of the camp system, The Gulag Archipelago.

While One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich is almost certainly the most widely read novel of the gulag, some regard Shalamov’s Kolyma Tales as stylistically more significant. They are often very short indeed and seem to be episodes, vignettes or events left to speak for themselves in prose of great clarity and simplicity, with little artistic embellishment. In this they have something in common with the spare, austere, journalistic style of the great short story writer, Isaac Babel, who was murdered in January 1940 on Stalin’s instructions.

In fact, Shalamov himself once said that he hated literature and aimed to write works that were neither memoir nor story nor literature. Whether this claim can be taken at face value, I’m not sure, but it is certainly the case that his stories are limpid and spare and one reads them feeling that they are the work of a writer who is exerting ruthless and steely control of his material and of the experiences that gave rise to that material.

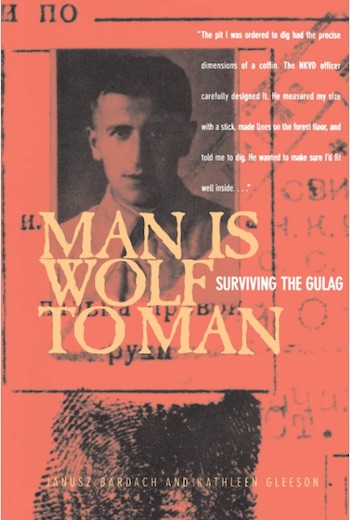

But what may well be the most extraordinary book about Kolyma is a memoir written some forty-odd years after Shalamov’s short stories and first published in 1998. This is Man is Wolf to Man, written by the camps survivor Janusz Bardach, with the assistance of Kathleen Gleeson. And strangest of all, this was not Bardach’s first – or even best known – book: he had previously written almost a dozen titles – but all of these were clinical and medical works, for Bardach survived the camps to become a world-renowned surgeon specialising in facial reconstruction. I bought Man is Wolf to Man on a whim in September 2002, picking up a remaindered paperback for £1.99, unaware of the book or its history, never having heard of Bardach, and – more poignantly – unaware too that he had died in Iowa City aged eighty-three less than three months earlier.

Born in Poland, Bardach was in his teens when the Nazis invaded in 1939. A well-known socialist activist in his small town he fled with the vast armies of refugees (particularly Jews) trying to get across the border into Soviet or Romanian territory. It was felt that his absence would better protect his family – especially his elderly mother who was ill with cancer – and girlfriend. He narrowly avoided death when marauding German planes swept down to machinegun the crowds of refugees. But there was almost as great a danger from advancing Red Army troops, whose political commissars regarded Poles – and especially Polish Jews – as at best politically unreliable and at worst traitors and Nazi collaborators.

Conscripted into the Red Army Bardach trained as a tank driver and mechanic but on his first outing in a new Soviet T-54 tank – then Stalin’s most secret weapon – he crashed while fording a river and was sentenced by court-martial for counter-revolutionary activity and almost shot. While being transferred to a transit prison he escaped. The systematic beating he received when recaptured almost killed him and took months to recover from. The description of some of the events Bardach witnessed are stomach-churningly brutal – especially the lawless and nihilistic urka gangs, the professional criminal class that ruled in the prisons and camps.

Man is Wolf to Man may not have the literary credentials of, say, Kolyma Tales, and I wouldn’t mind betting is still relatively little known, but it is an indisputable masterpiece of Gulag literature and should on no account be missed. Bardach’s is a voice from what seems the distant past, surviving into our own age. His memoir is currently available in paperback from Simon & Schuster UK. Kolyma Tales, in the original 1980 translation by John Glad is published by Penguin. A first English edition of the complete stories translated by Donald Rayfield is now available from New York Review Books Classics (2018) with a second volume to come in 2020.

Alun Severn

August 2019