Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 02 May 2018

posted on 02 May 2018

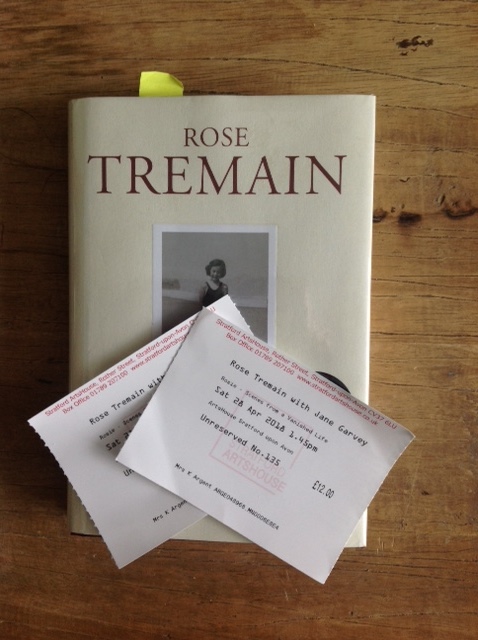

Rosie: Scenes from a vanished life by Rose Tremain

I have just finished reading ‘Rosie: scenes from a vanished life’ and so I was very pleased to be able to hear Rose Tremain talk about her autobiography at Stratford Upon Avon Literary Festival.

I really admire her novels and find them compelling well-crafted stories, so I was looking forward to enjoying this one. I’m sorry to say that I found that, although it gave me an interesting glimpse into her background as an emerging writer, I didn’t enjoy it very much. This might be because it includes so many sad memories that I felt quite miserable by the time I finished reading.

I was reassured to realise that I was not the only reader to feel like this as it was a theme that was highlighted from the outset by the interviewer, Jane Garvey (best known as one of the Woman’s Hour presenters on Radio 4). Her easy and friendly approach to the interview was perfect in setting an intimate tone and establishing a rapport with the author.

Much of the book centres on her early childhood which was coloured by very unsatisfactory relationships with her maternal grandparents and her parents. She describes how her grandparents had sent their only daughter to boarding school at the age of six, mostly because she didn’t seem to like her very much. The incident was only briefly alluded to but I had found it quite chilling when I read about it, particularly when Tremain explained that her mother had tried to reassure herself that her parents really loved her because they had bought her an expensive new coat to take with her. During the interview, I liked the way that Garvey shared my horror by really pressing Tremain on whether anything good could be said about boarding schools.

After her own parents had separated and her mother had remarried, Tremain had also been sent away from home with her sister when she was ten. Before that her closest emotional relationship was with her very kind woman employed to look after the children who they always called ‘Nan’. Nan was there because her parents, it seems, were far too busy working and socialising to spend much time with their children.

Tremain’s response to the interviewer’s question about the traumas of being sent to live away from home from a young age was interesting in that she characterised living away as being an opportunity to learn to be independent and to forge strong enduring friendships and passions in adversity. I recognise this as a common defence of this extraordinary upper class tradition that seems to involve having children only to give them into the care of others as soon as possible. This is a sensitive subject for Tremain because her parents were particularly keen to off-load their two children, something that she touches on throughout the book. It is to the credit of the interviewer that she did not press the point although she obviously found the idea of sending children away to boarding school very troubling.

The book apparently came about as a result of a conversation with Tremain’s daughter who is a professional psychotherapist. She wanted to know more about her childhood memories and I couldn’t help wondering whether she thought the experience might be cathartic for her mother. At first the book was a collection of scenes inspired by looking at family photographs and was designed primarily for private family reading but she then decided to publish it for a wider audience. Her daughter has apparently read the finished book several times and wept throughout each reading, so I am not alone in finding it painful.

I’m not convinced that it was completely cathartic because she still doesn’t really confront the coldness that dominated her childhood. She admitted that she has tried to rationalise the behaviour of her grandparents and describes them as being forever damaged by the grief of losing one son at the age of sixteen with a burst appendix and the other son as a soldier dying in the last month of WW1. They regarded their daughter as something of a nuisance and although she was the child that survived, the relationship was always deeply flawed. Although this meant that they were difficult to get close to, Tremain emphasises how important it was for her and her sister to be able to escape from grim post war London and to visit them regularly in the school holidays. The freedom to explore the wonderful Hampshire countryside where they lived also played its part in developing her confidence and imagination.

She finished by reading a very poignant extract about how she was let down by her parents yet again when they were invited to attend a school concert given by herself and others at The Queen Elizabeth Hall in London. All the other parents of the excited fourteen year olds were suitably thrilled and turned up to watch their daughters perform with the promise of treating them to afternoon tea as a reward. Tremain’s mother and stepfather declined the invitation to attend because they were otherwise engaged. Much to her surprise, her father (whom she hadn’t seen for four years) accepted the invitation and she spotted him sitting in the audience. But after the interval, she peeks through the curtain and sees that he had disappeared without bothering to speak to her. Deeply wounded, she was taken pity on by her friend’s family who took her out to tea with them. When I read about this inexcusably cruel behaviour, I felt very angry on her behalf but when she read it aloud, it brought tears to my eyes because I don’t think she has ever forgiven him – and why should she?

Hearing her talk eloquently about the book with Jane Garvey brought it alive and also served to reinforce how the dreadful experiences of childhood can help to develop resilience and imagination that can be valuable components to inspire a writer.

Karen Argent

April 2018