Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 16 Nov 2017

posted on 16 Nov 2017

Black Fire! New Spirits! Images Of A Revolutionary Radical Jazz In The USA 1960 – 1975 (Soul Jazz Books)

Let’s suppose you know nothing of the history of the Black civil rights movement in the USA during the 1960s and 1970s. Let’s also suppose that you know nothing of the generation of legendary black jazz musicians that were active at that same time. I suspect that after only a short time grazing over the stunning images in this book you’d soon start to put two and two together.

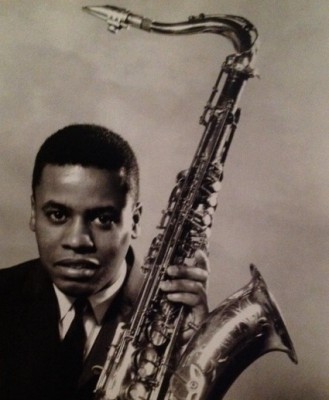

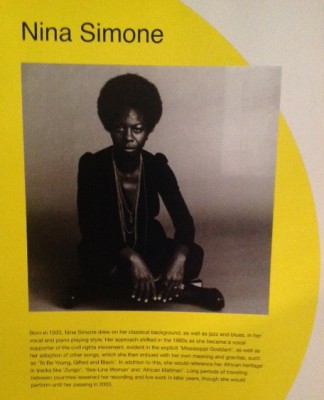

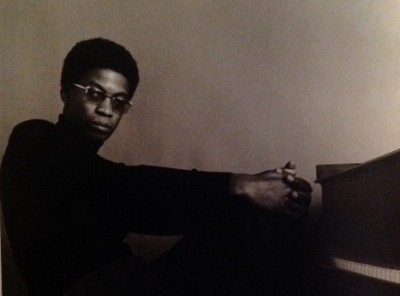

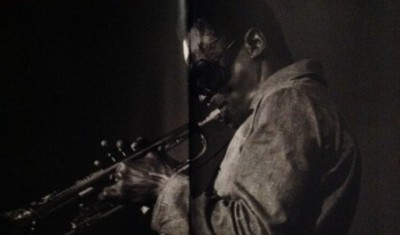

These were great experimental jazz musicians dedicated to changing their world through diversifying and revolutionising the musical form but they were also embodiments of the black struggle – cultural soldiers making their style and their music part of the political debate. If you doubt that look at their eyes, look at the way they look at you and look at Nina Simone’s defiant, unspoken, rhetorical question/challenge.

Stuart Baker’s excellent short essay at the front of the book makes much of this explicit:

Throughout this era critics, audiences, governments, nationalist activists, politicians, academics, diplomats and revolutionaries argued and vied relentlessly and intensely over the ground rules by which jazz should be measured, what its value was, and the criteria by which it should be judged good or bad…………….

The linguistic and politically motivated jazz wars were fought on the battlegrounds of the civil rights movement. Even before the radicalisation of jazz in the 1960s, an attitude and righteousness in jazz music ran parallel to collective African-American protest.

What we see here is cool as a weapon – image and music conscripted in the battle for civil rights and against the establishment. Revolutionary in every way.

Perhaps the most striking aspect of the photographs in this book is that one theme dominates all the imagery – the all-encompassing self-awareness of the artists – a self-determination so apparent in how they choose to present themselves to camera.

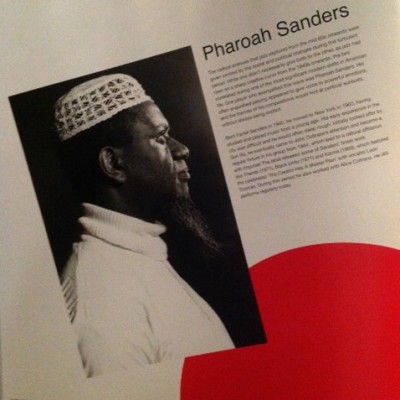

What follows Baker’s essay is a series of profiles (sometimes a bit sketchy) of specific artists or groups of artists – sometimes taken in portrait and sometimes snapped in ‘action’. It’s interesting to note just how often the sculptural beauty of the musical instrument nudges its way to the forefront of your attention. But the impact is cumulative as the sheer scope and scale of the talent unfolds from page to page. These are people aware at some unconscious level that they were rewriting the political as well as the musical landscape.

The book is generally nicely done if a little formulaic – the layout and format break no new ground but someone has had a great time putting this together. But I do have one fundamental gripe. Where the hell are the credits for the photographs? There are no attributions, no information relating to the circumstances in which the photographs were taken and no dates! It seems such an elementary omission that I went backwards and forwards several times looking for them thinking they simply had to be there and I was being an idiot. The latter proposition might well still be the case but I still can’t find and photographic information.

The book can be bought from the internet for around £15 or a little less and if, like me, you’re just in love with this kind of coming together of a favourite cultural form and a moment in political history then you’ll appreciate it.

Terry Potter

November 2017