Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 31 Jul 2016

posted on 31 Jul 2016

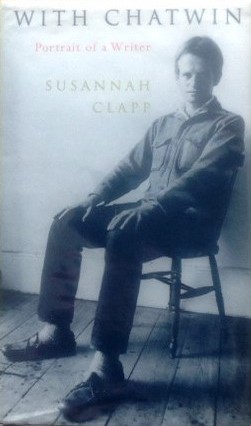

With Chatwin by Susannah Clapp

I always think I should like biographies more than I do. I think that one of my problems with this genre is that they frequently follow a structure I just can’t tune into – the forensic research many biographers put in and the comprehensive detail they uncover is undoubtedly impressive. It’s just that I find quite a lot of it dull – most often I really don’t care much about a writers grandparents or even the minutiae of their childhoods – and the chronological plod through their background from beginning to end just leaves me cold. I’m quite prepared to accept that this is my problem and that plenty of people do want this thoroughness but, nonetheless, I prefer my biographies to be short and sharp.

So, when I was given a copy of With Chatwin by Susannah Clapp, I was delighted to discover that this was anything but a formal or traditional biography. What Clapp has produced here is essentially an impressionistic hybrid of biography, gossip, memoir and literary criticism which is wholly appropriate to its subject matter. Bruce Chatwin was, according almost everyone who encountered him, a chameleon and an enigma who was almost impossible to pigeonhole. How much of his life story is theatre and how much of it the ‘real’ thing remains a matter of debate. Chatwin is almost impossible to pin down – and what this book demonstrates is that the absolute truth of his life is not the point and that the myth of Chatwin the author, the traveller and the socialite is what counts.

Clapp writes about Chatwin as a friend and from the outset it is clear that his friends are prepared to see anything he did as, if not loveable, then excusable. It’s very difficult to capture in writing what charisma is and how it works but Clapp has a go in the opening chapter called Chatwinesque where she tries to pin down the essence of the man. Clapp is well placed to try this having been the editor of two of his books whilst working at the publishing house, Cape, who decided to take a chance on Chatwin’s first manuscript of what would become In Patagonia. I’m not sure in the end she’s entirely successful but what she does do is present us with someone who is disconcertingly contradictory, utterly confident of his own skills and, I think, ultimately infuriatingly self-centred.

Rather cleverly, Clapp does take us through much of the same territory as a conventional biography without making it feel that way. So we get to see some of his school days, his early fascination with collecting and antiques, his career in Sotheby’s, his marriage, his time at Edinburgh University and his evolution as a writer. At the end Clapp also deals movingly with Chatwin’s illness and the dawning realisation that he had developed Aids – at this time virtually a death sentence. None of this is prurient or invasive and Clapp makes a point of not lingering on Chatwin’s sexuality – which was, characteristically, complex. That is not to say she ducks out of the difficult personal stuff, it’s just that she doesn’t feel the need to indulge us with private detail and I, for one, appreciated this tact.

Given her status as a top editor it’s not surprising that she provides us with some high quality literary criticism too – her insights into Chatwin’s published work are really first rate and I was particularly fascinated by the way she threw back the curtain on the creative process in respect of In Patagonia. I also liked her take on his last book Utz, written when he was very unwell, and which allows him to explore some of the issues from his time working in the art and antiques world. Chatwin freely mixes real life background and fiction – something that characterised all his work, even that which posed as factual travelogue.

Entertaining as it is, there are some weaknesses which tend to bother you the further into the book you get. I’ve already noted that Clapp was close to Chatwin and that her assessment of him and his life came from that perspective but she does hint on occasions that not everyone was susceptible to his charm – indeed some found him a substantial pain. However, these dissenting voices are not really given any sort of platform here and get brushed aside in a pretty perfunctory manner.

Again, although I applaud Clapp’s clear determination not to find herself picking over the detail of Chatwin’s sexuality, I really could have done with a better analysis about why Chatwin married Elizabeth and then stayed with her ( and she with him) throughout his life and in spite of his evident homosexuality (bisexuality?). She was clearly an important part of his life and yet we get very little about her or their relationship and this seems to me to be a significant absence.

Finally, Chatwin is known for his travel writing and described himself as a ‘nomad’ but you’d hardly realise that from this book which remains resolutely domestic – Clapp makes no effort to track his time abroad or to analyse the impact of travel on his character and the development of his ideas. An odd decision I think.

Having said that, I found this a thoroughly enjoyable read. I love Chatwin’s books but I always thought I’d have disliked him if I’d met him – and that is even more true now than it was before I started this biography. He seemed to know all the key movers and shakers, loved being part of the elite and hobnobbing with the rich and ‘tasteful’. He clearly loved being loved and didn’t treat many of his friends with the sort of thoughtfulness and respect they might have deserved and at a distance the charisma doesn’t mean that much. I long ago accepted that great writers are not necessarily going to be great people – a mould Chatwin fitted to perfection from my perspective.

Terry Potter

August 2016