Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 20 Apr 2016

posted on 20 Apr 2016

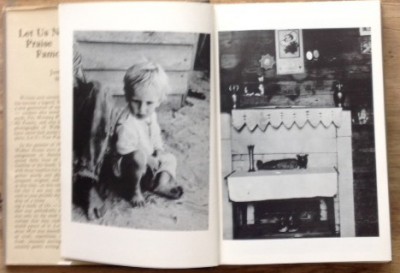

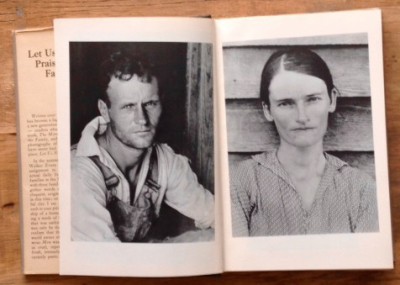

Let Us Now Praise Famous Men by James Agee with photographs by Walker Evans

When I started to get interested in photography as a journalistic tool as well as an art form, it wasn’t long before the name of Walker Evans started popping up. In particular the project he collaborated on with James Agee called Let Us Now Praise Famous Men was legendary.

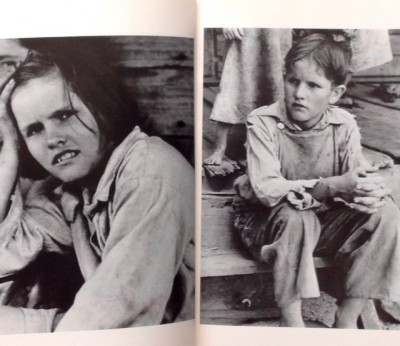

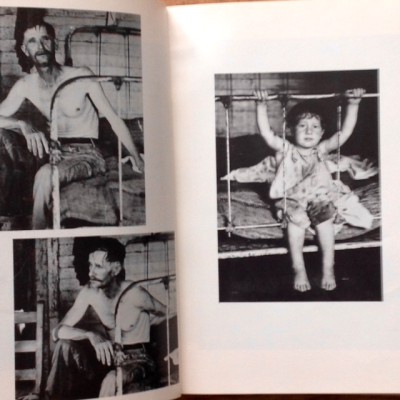

In 1936 Agee and Walker were commissioned to do some Fortune Magazine pieces revealing the hardships of sharecroppers in dust bowl America during the Great Depression. They spent only eight weeks researching and photographing the lives of two or three families but the results were stunning. Agee had in mind that the final product might run to three or four volumes but ultimately in 1941 only the first was published as Let Us Now Praise..

The book isn’t presented as a large format photography project but as a standard size hardback where the photographs are clustered together at the front of the book rather like a photographic essay on glossy plates before Agee’s prose kicks in.

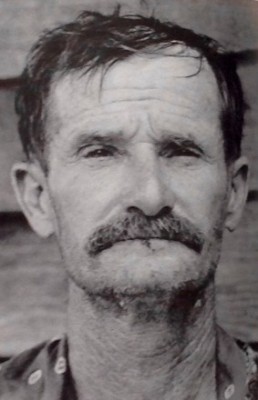

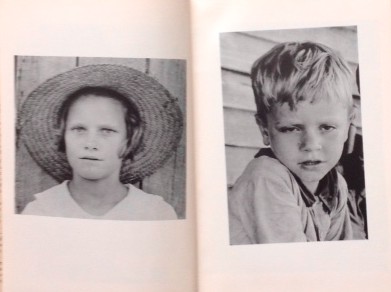

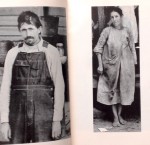

Without doubt it is the iconic nature of Walkers luminescent black and white documentary photographs that raises the book out of the ordinary and into something truly remarkable. The candid portraits of poverty are not just about the people but about the whole environment – these people are gaunt and hungry and the children have haunted eyes but much of the pathos also lies in their living conditions – bare shacks with wooden floors. It’s impossible not to call to mind Bob Dylan’s traumatic Ballad of Hollis Brown which tells the story of a farmer so desperate that he kills his family and himself simply to escape the suffering.

It’s not been clearly established just how influential Let Us Now Praise.. was in terms of influencing public attitudes and opinion but it was certainly impactful as far as other journalists and photographers were concerned. There are those who think that the authenticity of the photographs is open to question and claim that Evans ‘over- posed’ his subjects in the hope of getting more powerful images. But this claim has to be put in the context of the photographic practices of the day when posing your subject was routine practice and not construed as compromising the photographers key messages. As far as I’m concerned I am not even slightly bothered by the criticisms because these pictures capture something deep and lasting – a genuinely haunting tale of the way poverty kills the soul as well as the body.

Genuine first editions of this book will cost you a fair chunk of your savings – well over £3,000 – but there are plenty of affordable reprints available for much more modest prices and with perfectly good reproductions of the great photographs.

Terry Potter

April 2016