Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 17 Apr 2016

posted on 17 Apr 2016

The archaeology of working class writing : Part Two – Harold Heslop

Researching the issue of working class writers in the first half of the twentieth century seems to always lead back to the issue of adult education – usually sponsored by the trade union movement. The story of the emergence of this strand of workers education is – as frequently seems to be the case with the politics of the Left – riven with dispute and factionalising. At the heart of the friction seems to be the question of who controls and provides the curriculum – should this be delivered by professional middle-class educators with a sympathy for the trade unions and working class politics or should the educational process be in the hands of the workers themselves.

The establishment of Ruskin College in Oxford as a centre for working class education proved to be the battleground on which these conflicting ideas played out. Those wanting an explicitly working class control of educational content found themselves so at odds with Ruskin that they sponsored the founding of an alternative centre - the Central Labour College (CLC) which in turn led to the eventual establishment of the National Council of Labour Colleges (NCLC). These were promoted and badged, as the author John Atkins has said, as ‘an expression of working class self-organisation’. His book ‘Neither Crumbs or Condescension’ claims that the aim of this new movement was clear – to ‘build an adult education movement with solely working class support’. In doing so this new set-up would be the true heir of to the working class autodidacts who had demanded independence from educational specialists or any control over curriculum that could be construed as middle-class interference with an essentially socialist mission.

The CLC was primarily funded by the National Union of Railwaymen and the South Wales Miner’s Federation and by 1915 it was recognised by the Trade Union Congress as the co-ordinating body for a national network of labour colleges. In 1926 moves were made to try and merge the CLC with Ruskin once again but these proposals were defeated and by 1929 funding stopped as the trade unions faced the backwash from the economic downturn and the approaching slump.

However, the two decades of its existence produced some remarkable results – one of which was the emergence of writers like Harold Heslop (1898 – 1983). A miner in the Durham coalfield, Heslop was able to attend the Central Labour College in 1923 by way of a trade union-funded scholarship which gave him the economic capacity to write his first novel, Goaf. However, he struggled to find anyone in the UK prepared to publish his book and the first edition appeared only in a Russian translation - Pod vlastu uglya (Under the Sway of Coal) - and did not get a UK imprint until a decade later. Heslop’s book sold over 500,000 copies in Russia but he was only ever able to repatriate a tiny percentage of the sales royalties.

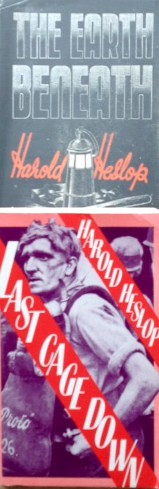

Heslop was always active in the politics of the Labour left and the trade union movement and stood for election on more than one occasion. He is remembered now for his two novels of life in the mining communities of the north-east – Last Cage Down (1935) and his final novel, The Earth Beneath written in 1948 – and by some distance his most successful in terms of sales.

For me, Last Cage Down, is the most engaging of the two novels even though it could be argued it is less accomplished in a literary sense. The Earth Beneath is largely focussed on telling a historical family saga of mining life which, to be fair, is quite slow moving and lacking a real dramatic thrust. However, it undoubtedly speaks to the unbroken thread of working class culture and history – the sort of narrative that illustrates what Raymond Williams was talking about when he spoke of ‘structures of feeling’.

However, Last Cage Down, is a much more didactic and impassioned polemic which reflected Heslop’s closeness to the Communist cause in the mid-1930s. David Bell in his book Ardent Propaganda: Miners novels and class conflict 1929 – 1939 puts it succinctly:

Last Cage Down shows Heslop's development in the articulation of political philosophy by stating a Communist ideology more explicitly. The conflicts between the miners of Franton and the pit management are seen specifically in terms of a class war, and though the conflict itself is only a small incident, it is linked to the many struggles that will bring about a revolution.

The view that revolution was possible was something that characterised the working class novelists of that period – and I have my suspicions that this may well be the core reason so much of their work has been airbrushed out of popular literary history.

There doesn’t seem to be much of Heslop’s work in print as I write this article. The posthumous autobiography published by Bloodaxe Books in the 1990s is the one that is most accessible and there is a 1980s reprint of Last Cage Down which can be picked up on the second hand market but it is expensive for a second-hand paperback.

Terry Potter

April 2016