Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 12 Mar 2016

posted on 12 Mar 2016

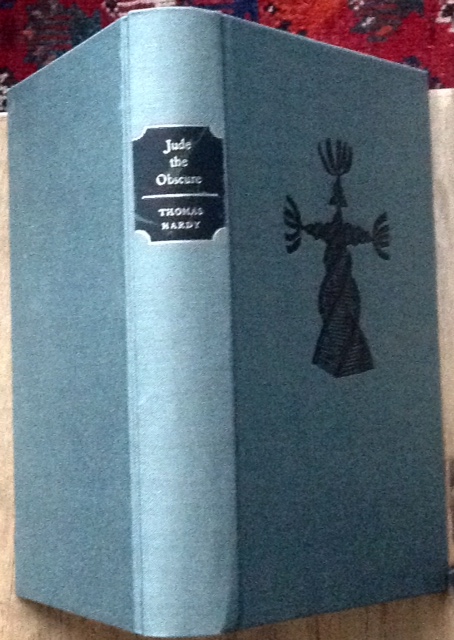

Living, loving and crying with Jude the Obscure

(This is the second instalment of a series of pieces reflecting on books that changed my life : the first – New friendships, frozen playing fields and Under Milk Wood – can also be found on this site. )

Take a bow Mr David Short. You taught English A level at Birmingham’s Bournville College in the early 1970s and although none of us told you - and you will almost certainly remember none of us - you were an inspiration. For me you were a teacher to be admired and emulated – later when I too trained to teach, it was your qualities that I tried to reproduce. What I most admired was your ability to show us how literature could be the doorway to a magnificent garden of ideas and that cultivating that garden would represent a lifetime of pleasure. You untangled the complexities of metaphysical poetry, guided us through the richness of Shakespeare’s Anthony and Cleopatra and made Shaw’s Major Barbara feel urgent and contemporary.

But most of all you clearly loved Thomas Hardy and you were determined that we should too. The set book was The Woodlanders, in my opinion a tedious novel that I could never really reconcile myself to. I found the machinations of the lumpen Giles Winterbourne, the fickle Grace Melbry and the smarmy Edgar Fitzpiers all too leaden and I just longed for them all to fall into a pit of ravening bears. However, Mr Short was a cunning devil because just when I thought that I’d had enough Hardy to last me a lifetime, he came up with Jude the Obscure. And here’s the cunning part: he didn’t make us read it – he read it to us!

I don’t think that until that moment I had ever been read to in this way. I have no memory at all of being read to as a child and I was never exposed to any kind of systematic reading or story telling at school – reading out aloud in school classrooms in those days in the schools I went to was more a form of torture than a mode of entertainment. But this teacher, sensing that we had probably had enough analysis and discussion after 90 minutes of a two hour lesson, gave over the final thirty minutes each time to the continuing travails of Jude, read with heart and feeling. Hearing it in this way animated the story and made Hardy’s preposterous misery-fest live. Jude Fawley’s desperate desire to escape his narrow class boundaries through education spoke directly and intensely to my own circumstances . Closing my eyes as the words washed over me, the thirty minutes became timeless and I walked every mile with Jude to Christminster (Oxford), shuddered at every shattering set-back, wanted to cry out and warn him not to fall into the wicked emotional traps set for him and lamented his poor children hanging themselves because they were too many.

The power of words to create a world of happiness, pain and heartbreak seemed to me to be literally magical. I have no way now of knowing how good a reader Dave Short was but that hardly matters – to me at that time it was perfect and constituted the most anticipated moments of my week. Even now, at any time I choose, I can regress into that classroom, in a half-timbered building as the lorries rumble past on the main Bristol Road and go through the door that takes me into the fictional Wessex of Hardy’s creation and, if I listen carefully, I’m pretty sure that I will also hear Jude Fawley declare ‘I be for Christminster!’

Terry Potter

March 2016