Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 23 Feb 2016

posted on 23 Feb 2016

Eric Ravilious

Few artists evoke the vanished – or perhaps, more accurately, imagined – England of the inter-war period as powerfully as Eric Ravilious.

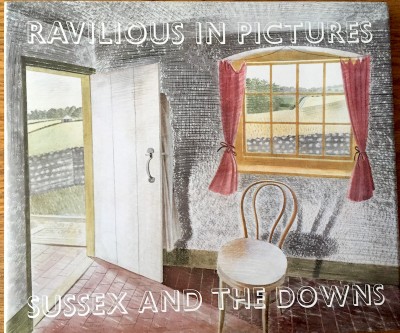

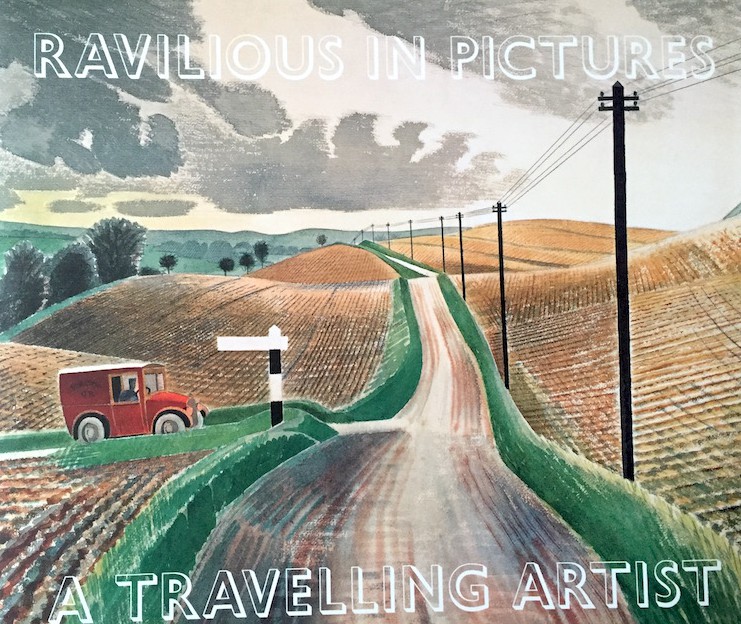

The flat somewhat stylised rendering of his watercolours and woodcuts, his modesty and quaint bohemianism, and the subjects that he loved – the deserted roads and chalk figures of the Sussex downs, farm machinery, country gardens, the interiors of cottages and attics and trains – all contribute a powerful nostalgia to his work. His death aged just thirty-nine while working as a war artist also seems fittingly but quietly heroic.

Indeed, everything about Ravilious combines to make him one of the most deeply loved of English artists, and yet popularity has not devalued his work and it continues to be the subject of some extraordinarily beautiful books.

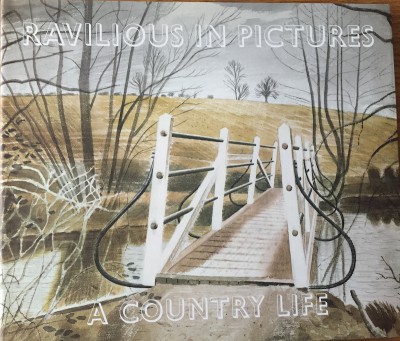

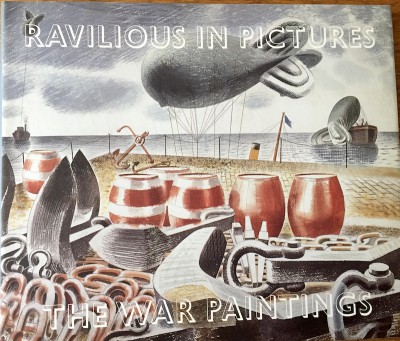

Four that deserve a place on the shelves of any Ravilious fan are the four volumes that make up Ravilious in Pictures, by curator and social historian James Russell, published by Mainstone Press, a small independent publisher specialising in the work of Eric Ravilious and his circle.

Each volume – Sussex and the Downs; The War Paintings; A Country Life; and A Travelling Artist – reproduces twenty or so watercolours, each accompanied by an elegant and informative essay. Each book is about 48pp.

The explanatory texts illumine the pictures and the life with the deftest of touches. For example, the 1938 watercolour ‘Wet Afternoon’ (in A Travelling Artist), depicts a solitary figure walking down a steep narrow lane with towering hedges on each side. A small chapel is visible. Russell explains that Kilvert in his diaries described this chapel as “short stout and boxy” with a “short bell turret”, the chapel yard enclosed by “seven great solemn yews”. The building reminded Kilvert of an owl.

But it probably wasn’t Kilvert’s loving description that had prompted Ravilious to make the journey here. He was in all likelihood visiting Eric Gill, whose religious/artistic community was nearby. Ravilious had chosen to walk and was accompanied by Guy Hepher, a friend, but Ravilious’s wife Tirzah had driven. Unfortunately, she found the narrow lanes a struggle and managed to get the car got stuck. A passing postman – despite having only one arm – helped her free the vehicle.

Each volume has its own joys but they all offer rich and vivid insights into this most English of artist’s work and the circumstances of its creation. We are fortunate that yet again Ravilious’s enigmatic and sometimes dream-like pictures have been well-served by a diligent and sensitive commentator and beautifully produced books. Highly recommended.

Alun Severn

February 2016