Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 21 Sep 2015

posted on 21 Sep 2015

Why are my books exploding?

Back in the early 1970s I worked in a bookshop in Birmingham run by a family of more or less dysfunctional brothers and sisters. Not that this manifested itself in an autocratic regime, quite the opposite in fact. Pay was not generous (when was it ever in the book trade) but they took a pretty liberal approach to staff discounts and turned a blind eye to generous ‘freebies’ from publishers that would often arrive in medium-sized brown cartons and be scavenged by staff on a strict hierarchical basis. I still fantasise over the monthly arrival of the box of samples of each month’s Penguin new titles.

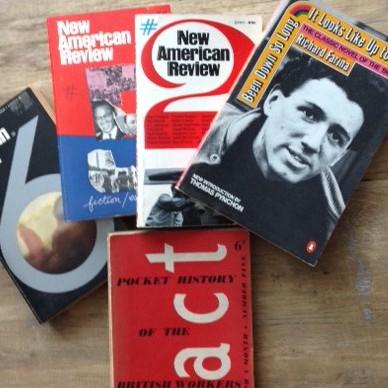

The result of all this largess was that handfuls of new paperbacks found their way home with me. But, despite my unrelenting acquisitiveness, only a tiny number have stayed put in my collection for all those years. The fact that there are so few left on my shelves is partly the result of my changing tastes, partly the fact that I’ve traded up to hardbacks but also because quite a lot of books from that period have bindings that have simply disintegrated. Open a Picador or Abacus paperback from that time and you’re likely to be met with a spray of powered glue and a fluttering of pages as they fly off around the room. I’m not accusing these two specific publishers of being unique offenders in this respect – plenty of Penguins, Quartet and New English Library from that period also suffer the same fate with even the most careful handling.

In retrospect the decade between 1972-82 seems to have been a bit of a nadir in terms of book production and design. At a time when the economy was heading towards a major recession everyone was looking for savings and it wasn’t just book production that suffered in terms of quality control. Anyone who was/is a collector of vinyl records will tell you that the quality of L.P. records took a nose-dive around this time – something which certainly paved the way for the introduction of the c.d.

It wasn’t just paperbacks either. Hardbacks which had previously been sown began to be glued into cheaper pressed card covers rather than cloth bindings and the dreadful cracking sound that greeted you if you had the courage to fold open the spine would leave you in little doubt that its back was well and truly broken. I have no idea what kind of cheap glue was used on this generation of books but it didn’t take that long for the spines to dry out and then – poof! – a paper-fountain rather than a book.

I guess from the publishers point of view this was a version of the principle of built-in obsolescence but from a readers point of view watching your treasured memories disintegrate in your hands can be a traumatic experience. It’s good to be able to say that things have got decidedly better in many ways since those dog-days. I get the distinct impression that the publishing world has decided to fight back against the digital threat by making books an object of desire again. I think it’s been something of a golden period for book design as publishers use their creative imaginations to make customers want to pick up the physical book. Paperback designs are often stunning and hardbacks now have a real sense of the chic about them. What I particularly like is that they’ve gone for design values rather than gimmicks and I guess it follows that if you’re going to put a lot of resource behind the design you also have to manufacture something that doesn’t disintegrate in your hand. The renaissance of the beautiful book goes alongside the reimagining of the vinyl record – also based on premium rather than budget manufacture – and both of them point the way to the future in which the physical object will have its own space alongside the virtual and the digital.

Terry Potter

September 2015