Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 06 Aug 2015

posted on 06 Aug 2015

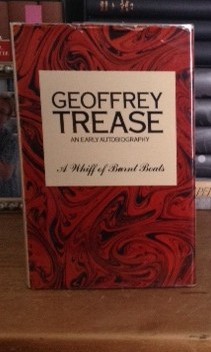

A Whiff of Burnt Boats by Geoffrey Trease

I’d be willing to bet that not too many people outside of a small group of children’s literature aficionados have even heard of Geoffrey Trease and probably even fewer have read him. Having said that, the reference books will tell you that Trease was instrumental in changing the nature of books aimed at what would now be called the young adult audience by introducing a gritty reality and an overtly political agenda into his historical adventure stories. In particular, books aimed at boys would never be quite the same again after Trease’s retelling of the Robin Hood story – Bows Against the Barons (1934).

But Trease was interesting for much more than just literary innovation. In the period after the end of the First World War and before the start of the Second, Trease found himself in the heart of Socialist radical London literary circles, a founding member of the Promethean group of writers and feted in post-revolutionary, pre-Stalinist purge Soviet Union. He went on to write over one hundred titles but this inter-war period was especially colourful and exciting.

So when I found a signed copy of A Whiff of Burnt Boats (which is the volume of autobiography that covers this period) in our local bookshop I was thrilled to pay the measly £7.50 that was being asked. I settled down expecting to be intrigued and fascinated by a man who was a best seller in the Soviet Union, who corresponded with George Orwell, who spent time in an East End Settlement project, who wrote for Unity Theatre and who was published by Gollancz at the peak of CPGB influence. How could it fail to hold any reader spellbound?

Well, how wrong could I be. This is possibly one of the dullest, flattest autobiographies I have ever read. All of the riveting events mentioned above are touched on but so briefly I would defy you to draw anything substantial from the plodding, matter of fact way it’s narrated. At no point does Trease really discuss his political views or how he developed these and whenever a story begins to open up, he moves quickly to shut it down. What we do get, in tedious detail, are the everyday comings and goings of his seemingly unexceptional childhood, an anguished portrayal of his precocious academic prowess at school (yawn) and subsequently how this all blows up in his face at Oxford – which he leaves early without seemingly causing anyone too much anguish. What emerges here is a solid middle class, even bourgeois, upbringing that in no way explains how he finds himself at the heart of the emerging Socialist movements of the day. What a missed opportunity.

This book is only a couple of hundred pages long and it’s not until we enter the last quarter of the book that we start to get any perspective on the political environment he was moving in – and yet this is the real and substantially interesting period of his life that anyone reading this would want to know about.

I can only imagine that Trease’s politics drifted to the Right as he grew older and he was embarrassed over his radical past and simply wanted to gloss over it. You’d be better off reading Trease’s YA fiction than this sad apology for an autobiography. He certainly learned a lesson from the hero of Sherwood Forest - I feel robbed.

Terry Potter

August 2015