Inspiring Young Readers

posted on 11 Nov 2018

posted on 11 Nov 2018

Can Picture Books explain the WW1 Armistice Centenary to younger readers?

There is no getting away from the fact that war and its many consequences are ugly and painful. In the light of this year’s Armistice Centenary celebrations, I can imagine that publishers have spent long hours with authors and illustrators trying to find a way of marking the momentous occasion in an appropriate and sensitive manner. As a result there have been several splendid picture books appearing in the shops over the last few weeks that treat the subject in very different ways.

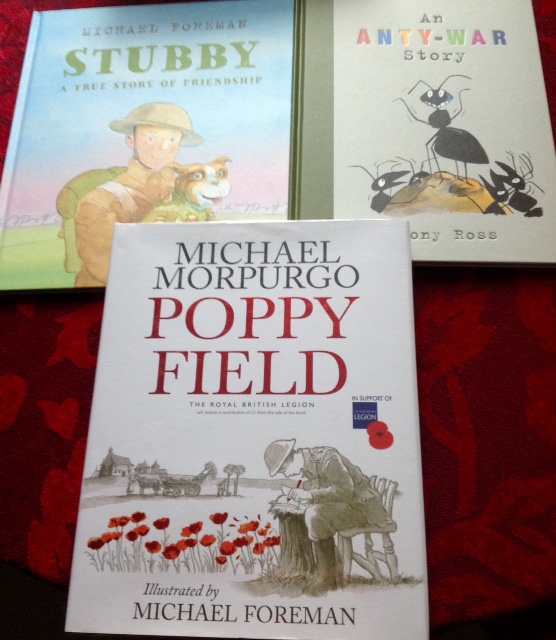

Stubby: A true Story of Friendship by Michael Foreman

This author-illustrator is one of my favourites and has often written about the subject of war in his many picture books that include being the lucky survivor of a direct hit on his childhood home during the Second World War. This time he has chosen to retell the true First World War story about a stray dog that was adopted by Corporal Conroy who was a young US soldier from Connecticut about to go to war. On the front line in France Stubby apparently performed many heroic deeds and was probably the most decorated WW1 war dog. He deserves to be the central character of this very accessible tale that gives an insight into what he might have experienced alongside the soldiers.

Foreman’s distinctive paintings on double page spreads convey the huge expanses of land and sky in America and in France. He also hints at the horrors of action when a violent explosion in the distance shows two men falling as their comrades scramble out of the trenches. The next pages show Stubby lying injured in the thick mud as the colourful sky flares behind him. The plucky dog is taken to hospital, recovers from his injuries and then returns to the front six weeks later now wearing an army jacket replete with many medals. The way that war is presented in this picture book is relatively romantic and soft with no inclusion of dirt, pain or even much sorrow. Perhaps this is the overall intention because, even in the hospital the badly wounded men smile as Stubby cheers them up with his trick of saluting the soldiers with his paw. The French villagers all look down fondly at him as they stand against the background of wrecked buildings. The emphasis in this picture book is very much about the importance of friendship and the eventual peace. I liked the message about recognising that soldiers from both sides had much in common:

‘Winners or losers, we are all survivors. The enemy are young men like us, and we all just want to go home’.

Poppy Field by Michael Morpurgo, illustrated by Michael Foreman

Poppy Field was written in support of The British Legion which receives a £1 contribution from every sale and is based on the story behind the poppy as a symbol of Remembrance. It follows the story of the Merkels, over the course of four generations and how war has shaped their family history. This creative author and illustrator are firm friends and have already collaborated on many books aimed at children of all ages. It is clear that they work together with tremendous ease and so produce seamless narratives where the text and illustrations are in perfect balance. Morpurgo is always so good at weaving in plenty of history as part of a compelling story and he does this to powerful effect once again. He describes how the Flanders landscape has changed from the dreadful No Man’s Land of WW1 to becoming the ‘Poppy Field’ that is part of the farm where the Merkel family live and work. Martens Markel is the young first person narrator who explains that:

‘Grandpa has told me this story over and over again. It is really several stories in one, one long family story, full of strange meetings’.

Although aimed at more sophisticated readers with much more text, longer and with a more complex plot, it is interesting to compare the overall tone of this one with Stubby: A True Story of Friendship. This time Michael Foreman uses a restricted colour palette of greys and reds which is very effective in conveying the sombre subject of war and death and imbuing it with a quasi- religious quality. The colour red represents hope whenever it appears in the story and there are some parts illustrating the gloomier side of the fighting where everything is just muted grey. On the final pages the numerous red poppies dominate in the foreground and three white doves of peace soar against the sky.

The end of the story is followed by the poem In Flanders Fields by John McCrae, who is rather cleverly included as a character in the story. There is a fascinating afterword written by the Right Revd Nigel McCulloch KCVO who was a former National Chaplain of The Royal British Legion which provides plenty of historical information about why and how the poppy has retained its significance when remembering WW1.

An Anty-War Story by Tony Ross

My third choice is very different but an important part of the mix because it challenges the very notion of war which isn’t really covered in the other two at all. Ross is another prolific and much loved author illustrator renowned for his often quirky picture book subjects. In my view, he is never sentimental but always spot- on with his social commentary and I also enjoy his rather manic drawing style that is full of energy and wit.

The picture book tells the story of Antworld which is at first a happy and peaceful place in which everybody is very busy but nobody has a name, except for an ant called Douglas. It appears that Douglas is very unusual because he is destined to question everything around him. The nameless ants just carry on doing what has always been done in the past and Douglas decides that he will do the same, so that he can fit in. When he is fully grown with a big head and big teeth, he discovers that he is destined to be a soldier and he feels very proud. He learns about carrying a rifle, wearing a uniform and how to defend Antworld.

The illustrations by Ross are as excellent as ever throughout but I particularly liked the one where he joins ‘the beautiful line of soldiers as they marched up and down and the little ants waved flags.’ The soldiers are followed across the pages by a band dressed in vibrant red outfits. Above the parade we can see officers riding green grasshoppers cheered on by the crowds and in the foreground we see the silhouetted heads of many more ordinary ants who are watching them go off to war and glory. What could possibly go wrong?

There follows a dramatic illustration showing bombs whizzing across two pages. The next page shows a red background that bleeds to the edge of the pages with the word ‘Bang’ emblazoned across in no uncertain terms. The last page shifts to a grey and ochre palette depicting the shapes of men fighting at the front against a desolate landscape – a fragment of the word ‘ Som …’ in the corner of the picture and the simple text stating ‘ The end’ in the opposite corner. The final page shows a war memorial with all the names listed on it as ‘A’ apart from ‘Douglas’. This is very moving stuff and I think would be a fantastic book to discuss with children because it is both subtle and explicit at the same time.

In a recent interview for the Association of Illustrators, Ross points out: ‘Although war is important, it is only by understanding it, we can find better solutions. The more we understand something, the more we can be in control, and limit it’.

https://theaoi.com/2018/10/12/tony-ross-an-anty-war-story-interview/

For this reason, An Anty-War Story gets my vote for the most powerful and unusual picture book of this impressive bunch about this challenging subject.

Karen Argent

November 2018