Inspiring Young Readers

posted on 04 Jul 2017

posted on 04 Jul 2017

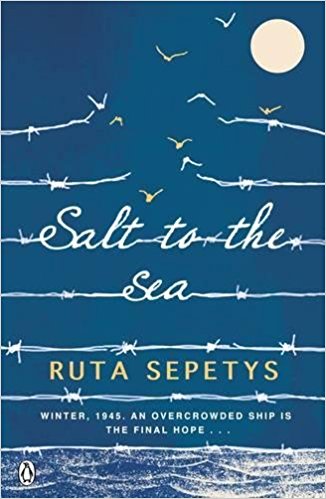

Salt to the Sea by Ruta Sepetys

Ruta Sepetys, an American author of Lithuanian heritage, has written an ambitious, award winning, young adult novel about one of the forgotten tragedies of the Second World War. We are accustomed to hearing about the loss of life associated with the Titanic or the Lusitania but for reasons that are quite hard to understand we seem to have lost sight of, or ignored, the sinking of the Wilhelm Gustloff in 1945. Some 9,000 lives were lost - up to 5,000 were children while many others were refugees or wounded German soldiers who had no chance of surviving in the icy sea after Russian torpedoes struck the ship.

Sepetys’ book provides quite a detailed historical appendix to her story which explains the background and her own family connection to the tragedy. As the Second World War was coming to its end, the Eastern Front was being overrun by Soviet troops determined to push on through the Baltic states and Poland on their way to Berlin. Civilians and German soldiers were pushed to the only open ports on the Baltic in search of ships that would take them to Germany and comparative safety but the Russian pursuit was unrelenting and unforgiving and the weather brutally cold.

Sepetys tells this story in quite a daring way, entwining the point of view of four young people who essentially tell the tale almost as a relay – handing the narrative on to each other page after page. The voices we hear are:

Jonana Vilkas who is a Lithuanian nurse and who becomes the moral centre of the group of people she leads to the port and their destiny with the Wilhelm Gustloff .

Florian Beck, a young, handsome Prussian who is on the run from his job working for the Nazi Party art establishment.

Emilia Stożek, a teenage Polish girl who is discovered to be pregnant but who sees Beck as her ‘knight’.

Alfred Frick, an inadequate young German sailor who has put all his trust and belief in Hitler and his Aryan philosophies.

In addition the group has other strong characters that stay bonded to Vilkas, Beck and Stożek – an elderly shoemaker, a blind girl, a young boy and an exceptionally tall woman – and these individuals give the group a range of voices and additional useful survival skills as they trek through the frozen winter landscape.

All of the central characters have rich back-stories that Sepetys exploits beautifully and the shadows of their past give the book their substance because the central story is really quite basic. These histories bring mystery, romance and jeopardy to what is an arduous and dangerous journey to escape the ultimate peril of capture, imprisonment and possible death. The richness and mystery of these backstories help to overcome one of the author’s biggest problems – we already know the outcome; we know it will end badly. What we don’t know, however, is whether Sepetys will save anyone and if she does, who.

The fact that we know this story must end disastrously gives the book a sense of fatality and, in this respect, it has similarities to Hardy’s famous poem about the sinking of the Titanic, The Convergence of the Twain. Hardy builds a story that tells how the boat and the iceberg become inseparably symbiotic and brought together by the inevitability of fate and Sepetys has taken us down the same route using a very similar set of devices to get there.

I’m not going to reveal here how the story plays out because you’ll want that kept fresh for when you read it yourself. What I can say is that, by the end, you’ll be absolutely gripped and emotionally drained by the experience.

But, I think it’s fair to say, the complex narrative device of using four points of view is not wholly successful – especially at the beginning. The storytelling baton passes from character to character far too frequently and I would have liked to have been given the chance to spend a little more time with each of them at the outset. The rapid cutting felt chaotic at times and meant that, at the beginning, it was quite confusing and hard to stick with. Such rapid transfer of the story from one person to another worked against the development of distinct and clear-cut voices that would have allowed the reader to become familiar with the distinctive perspectives.

Having said that, I’m glad I stuck with it because 50 or 60 pages in you’ve become accustomed to the structure and you’ve been hooked by what might happen to the characters. When it was announced that the book had won the 2017 Carnegie Medal I was surprised – the competition was strong – but ultimately and despite my initial reservations I felt it was a worthy winner because it’s a rich broth of a book that is both a tragic and uplifting experience.

Terry Potter

July 2017