Inspiring Young Readers

posted on 21 Nov 2016

posted on 21 Nov 2016

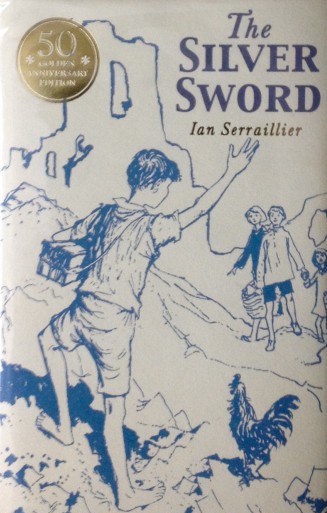

The Silver Sword by Ian Serraillier

The terrible conflicts in Iraq, Syria and Afghanistan, the civil wars in Somalia, Ethiopia and what is now Eritrea, the continuing war in Yeman and tensions in Palestine have all created a growing awareness of the plight of refugees fleeing from these dangerous places. Add to that the continuing economic travails of countries in sub-Saharan Africa combined with the fight for scarce resources that will only get scarcer and the scene is set for the relatively affluent West to develop a full-blown moral panic about being ‘invaded’ or ‘swamped’ by alien ‘others’ who will bring chaos and social disruption with them.

UN figures show that in 2016 somewhere in the region of one million refugees passed across or moved into Europe and this has been enough to trigger a brand of right-wing nationalist and protectionist politics that is currently enjoying ascendancy as populist politicians pile onto the anti-immigration bandwagon. And as difficult and unsettling as all this is – and I suspect it can only get worse – the problem of large-scale migration in the wake of conflict and social breakdown is not in fact new or unprecedented despite what the tabloid press might want people to assume.

In truth the problem we face today is dwarfed by the scale of the refugee crisis following the ending of the Second World War and this is something we seem to forgotten as a society. So, I was delighted to discover Ian Serraillier’s tale of unaccompanied refugee children in 1945 Europe which highlights superbly the fact the we have been here before - and solved the problem before.

The Silver Sword is a relatively simple tale of determination, fortitude, survival and humanity. As the German army is heading for defeat and retreats in the face of a Soviet advance from the East, the Baliki family from Poland have the problem of how they will find each other as the war comes to a close and the Allied armies are carving out their spheres of influence. The father, Joseph, escapes his prison camp only to find his family are believed dead when their house is destroyed by fire. He, however, believes they could still be alive and, following an encounter with Jan, a street-urchin surviving on his wits, Joseph entrusts him with a message for his family that he has gone to Switzerland. To seal the deal he gives Jan a silver sword – a small letter-opener in the shape of a sword that Jan treats as his inseparable treasure.

Joseph is right – his children have survived; Ruth, the older girl and now surrogate mother to Edek and Bronia have to make their way in the post-occupation chaos alone. A series of coincidences result in the children being thrown together with Jan – who is now virtually feral – and together all four resolve to head for Switzerland.

The rest of the story is the nature of that journey and the hardships and trials they face as they make their way through Poland, into Germany and eventually to Switzerland. Jan’s street skills are both a help and a hindrance and Edek becomes very ill with TB along the way but, and this seems to me to be the most important message of this book, it is the simple acts of humanity from strangers along their journey that ultimately allows them to succeed. Just when all hope seems lost there is someone who is prepared to go against orders or do something brave and extraordinary to help them. Even those who should still be their ‘enemy’ demonstrate that they are better than the politicians and the ideologies that have destroyed their world. In the end the indestructible nature of the human spirit triumphs.

The book was written in 1956 and is now regarded I understand as a landmark children’s classic. To be honest, I initially found the style a bit stiff and oddly formal but once I had got used the voice and the Fifties vocabulary, I was completely immersed. This later 50th anniversary edition of the book also has C. Walter Hodges original illustrations but the real bonus is an extended afterword by Serraillier’s daughter which gives some intriguing additional background and casts light on the way the author came to view the book himself.

All in all, this is a book for our times but I wonder now just how many younger readers encounter this kind of novel – I have a horrible suspicion that school teachers and librarians will just dismiss it as ‘dated’ and go looking for something that is more contemporary. What a waste.

Terry Potter

November 2016