Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 14 Apr 2024

posted on 14 Apr 2024

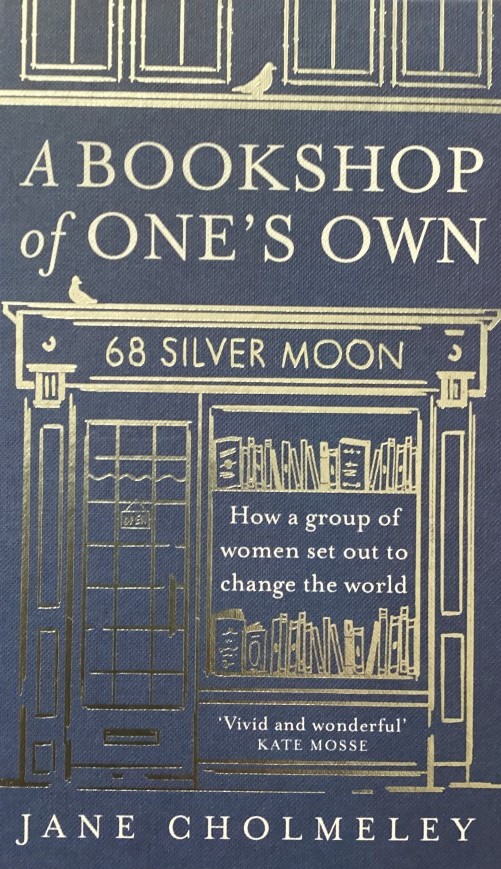

A Bookshop of One’s Own by Jane Cholmeley

The idea of a bookshop dedicated to stocking the work of female writers – fiction and non-fiction with a focus on emerging feminist theory – is one that might not, these days, seem especially revolutionary. But, go back to the late 1970s and early 1980s and this would have been at the very cutting edge of what we’ve come to call the ‘culture wars’ and, Jane Cholmeley’s A Bookshop of One’s Own is well aware of this. It’s an invaluable documenting of the birth and (often troubled) lifetime of the Silver Moon bookshop which – with the help of grants from the Greater London Council – opened on the Charing Cross Road in 1984 and survived until 2001.

Cholmeley and her partner, Sue Butterworth, conceived of the idea of the shop when they were considering their work futures – which seemed bleak at that time with both facing a period of unemployment. They decided they should try and do something that excited them rather than just fall back on a safe alternative. Both were dedicated to and involved in the feminist movements of the time and they combined this with their love of books to come up with the idea of what would become Silver Moon.

However, they were also realistic enough to know that this was a project they couldn’t do on their own and so they invited a friend – Jane Anger – to join them in taking on what turned out to be a roller-coaster of a project. Cholmeley takes us step-by-step through the shop’s birth-pangs – all the grant funding bureaucracy, problems with premises and a few blips in their relationships with other feminist bookshops also emerging in London at that time. I suspect, you, like me, will be astonished at the volume of documentation she must have kept in an orderly and accessible way in order to share such detailed information with us – we are told about the budget calculations, for example, down to the last pound!

The idea for the bookshop was to create something of a safe-space for women – including a café and a meeting room – so on top of books they also had to learn the ropes around what is involved in keeping a café and running a community resource. It was, Cholmeley observes, like opening two brand new businesses in one go.

I think the book comes to life when we start to hear about the customers and the various full and part time staff members that come and go. Back in the 80s it was almost impossible for a project like this not to attract its unfair share of attention from those (mainly men) who were offended or wished the project ill. Dealing with strident sexists and a parade of sexual perverts of one kind or another was a frequent occurrence alongside the usual vicissitudes of keeping a business afloat and dealing with publishers.

This kind of book is invaluable in putting the history of such an important part of the cultural landscape on the record. Cholmeley is a thorough guide to the realities of what it meant to be counter-cultural in a time when Thatcherite values were ripping through the body politic. It has to be said that she isn’t, in my view, a natural born writer – there are times when issue feel over-laboured and the prose rather galumphs along rather than taking flight. But, equally, there are some preciously vivid moments of joy and disappointment that remined me of the highs and lows anyone setting up projects always have.

Currently only available in hardback but the paperback can’t be too far behind.

Terry Potter

April 2024