Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 19 Jan 2023

posted on 19 Jan 2023

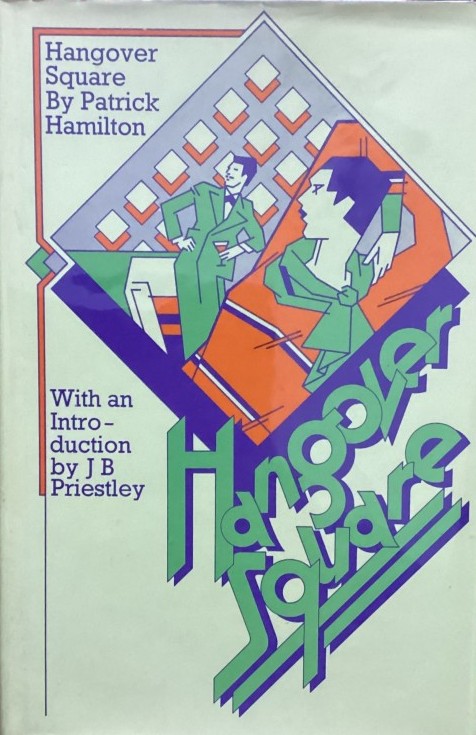

Hangover Square by Patrick Hamilton

It’s 1939 and the world is on the verge of war. Society is about to find itself involved in bloody existential conflict and in this shabby London of Earl’s Court bedsits and cramped, long-lease hotel rooms amongst the would-be Bohemians and theatrical aspirants, there’s an atmosphere of alcohol-fuelled despair.

Hamilton’s 1941 novel creates an unstinting atmosphere of inevitable doom and gloom and his storyline heads for the kind of cataclysmic end that will mirror the wider social slide to disastrous war. It’s a world in which drinking, pubs, selfishness and nihilism are the very fabric of existence and pretty much the only things this small cast of characters can imagine.

George Harvey Bone is a big man, physically, but a lost soul spiritually. He’s a friendless man who is haplessly in thrall to an attractive young woman, Netta, who has no scruples when it comes to seeking a way into theatre world and coldly exploits Bone’s worship of her. Netta is well aware of her power over Bone and, with the assistance of her close friend, Peter, she ruthlessly takes whatever she can from him. In his introduction to the 1972 edition published by Constable, J.B. Priestley puts it this way:

“His adored Netta, on whom he wastes so much time, attention, deeply-felt longing, is not only a selfish little bitch, but, along with her closer friend, Peter, seems to represent some principle of evil.”

Bone’s life of drinking and obsessing over Netta and her odious crew is acutely and depressingly observed in terms of the squalid details. Rooms are stale, ashtrays are full, unwashed clothes litter Netta’s untidy little flat and we see it all through the tortured eyes of this man who feels, in any situation, a misfit.

Bone, we also discover, has an escalating mental health problem which he characterises as ‘blank’ periods – times when he suddenly becomes disassociated with the world, experiencing everything in a ‘deadened’ state. During these periods he feels compelled to plan the murder of Netta and Peter, free himself from their control and move to live in Maidenhead. Admirers and critics of the book have speculated over what mental health state Hamilton was trying to describe here – I’ve seen schizophrenia, bi-polar and fugue-states mentioned – but whatever the specific illness, the result is genuinely chilling as Bone ‘snaps’ from one reality to another.

Netta has set her sights on finding her way into theatre world by making herself desirable to a big-time theatre producer, Eddie Carstairs, who, it turns out, has a connection with Bone’s only true friend, Johnnie. Netta’s brazen manipulation of the situation seems to escalate the pace of Bone’s mental collapse and triggers the descent into the final end-game.

I don’t think it would be wise to say more about how this all plays out but it wont be much of a spoiler to say that a tragedy is just around the corner.

Until I read this book I really thought it would be impossible to come across a more depressing description of the seedy underbelly of pre-war England than that which is conjured up by George Orwell in Keep the Aspidistra Flying but this book takes it a step deeper. The sad fringes of respectability, a bogus bohemia, is ruthlessly exposed and the world of pubs and incessant drinking has rarely been made less attractive.

I wondered at first whether I could stay with the book and whether I was strong enough to withstand this dive into such a depressing world but I’m glad I did because ultimately the book has a magnetic quality that grips you and refuses to let go until the dreadful end.

Paperback copies of the book can be found for under £10 but hardbacks, even later reprints, seem to fetch a premium price.

Terry Potter

January 2023