Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 08 Feb 2021

posted on 08 Feb 2021

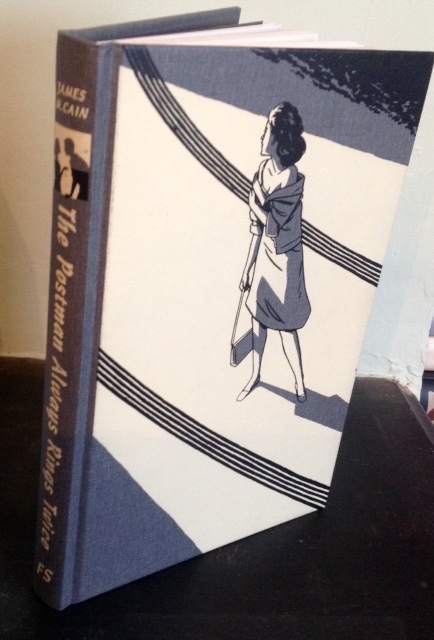

The Postman Always Rings Twice by James M. Cain

Published in 1934 when Cain was already 40, The Postman Always Rings Twice was the first of what would be a run of novels – including Mildred Pierce and Double Indemnity – that many think of as quintessential examples of the ‘hard-boiled’ crime novel. Their reputation has undoubtedly been enhanced by the 1940s film versions of the books that helped created the crime noir genre that became so popular and well-regarded.

TPART is a pretty extraordinary reading experience – it’s short but incredibly intense and the reader can’t help but feel that they have been dragged into the pressure-cooker atmosphere of smoking tension and sexuality. It feels as if you share the space with the characters but that you’re set off at an advantaged position and able to see the story of a passion that is out of control unfurl with an almost classical tragic inevitability.

Drifter and general wastrel, Frank Chambers rolls up to a rural diner in California to find it is run by a Greek owner, Nick and his wife, Cora – with who Chambers immediately establishes a sort of inescapable electricity. That the two are going to embark on a doomed liaison is obvious from the very beginning and we also know that this is going to be stormy.

Cora is unhappy with Nick and confesses to Frank that she would be open to a plan to do away with her husband – an act of violence that mirrors the sadomasochistic relationship she has established with her new lover.

As it happens, the plot goes farcically wrong but by a twist of luck Nick and the police believe that the attempt on his life was an accident and the two would-be murderers part when Frank decides to go back on the road. But the lure of Cora is too much for him and, foolishly, he returns to the diner and Nick, unaware of the bond that exists between the two would-be killers, welcomes him back.

A new plot is hatched and this time they carry it through by way of a contrived car crash. But under pressure from the police and the judicial system the two lovers separately betray each other with the result that Cora is accused of attempting to kill both men.

She escapes punishment however because of a clever lawyer who evokes a technicality and gets her released. Cora and Frank find a sort of resolution and resolve to stay together but the truth of their pact to kill is also known to Cora’s lawyer’s assistant who decides to blackmail the pair – which can, of course have only tragic consequences.

There is an ironic twist to the end that I’m not going to reveal here but leaves Frank in a position where he can narrate this story as he awaits his fate.

As is the case with novels by Raymond Chandler or Dashiell Hammett, the plot of the book always takes second-place to the creation of an atmosphere and a sort of febrile tension that carries you through. Any sober examination of the plot or of some of the absurd coincidences that enable the plot to work would lead you to think the whole thing would fall apart – but it doesn’t because you are held, or, perhaps more accurately, stuck to the story in a breathless heat of anticipation.

The overt sexuality and sexual violence led the book to be heavily criticised by a range of commentators – and not all of them from the moral right-wing. Raymond Chandler, hardly the most upright of writers himself, felt very strongly about Cain’s penchant for sexual violence. Graphically, he criticised Cain in these terms:

“Everything he touches smells like a billy-goat…He’s every kind of writer I detest…a Proust in greasy overalls…the offal of literature.”

A bit harsh I think.

The other issue that can’t be avoided is the book’s title – there is no postman in the book and no-one rings anything twice. Why Cain selected this title remains a cause of speculation and, as is the case with so many of these literary enigmas, you pay your money and you take your choice of the various convoluted explanations that have been put forward. I’m going to leave it with you but I’m most convinced by the idea that ‘the postman’ here is fate or destiny – but I could, of course, be completely wrong.

Terry Potter

February 2021