Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 13 Dec 2020

posted on 13 Dec 2020

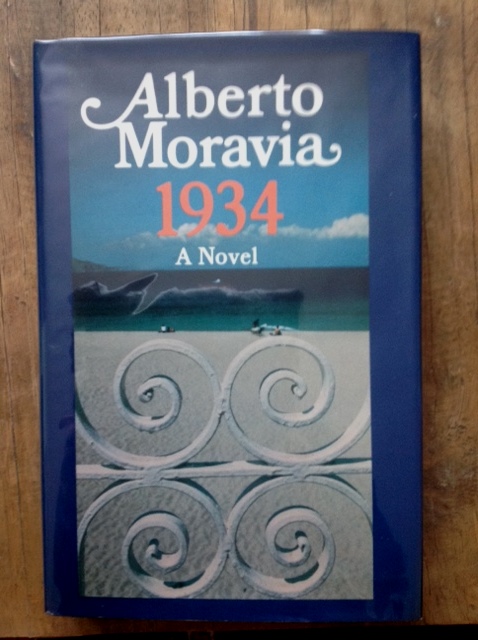

1934 by Alberto Moravia

Moravia (1907 – 1990) was one of Italy’s most prolific and widely translated 20th century authors – and one of the most politically committed. Moravia’s career was, in many ways, defined by his opposition to Fascism and he remained a member of the Italian Communist Party long after many others had abandoned it. His commitment to anti-fascism shaped much of his writing and meant that a good deal of what he wrote had to be allegorical in order to avoid censorship rules. But, in any case, Moravia’s interests were not crudely in the field of social realism or Leftist propaganda and he was intent on exploring the relationship between politics at a State level, a personal level and at a sexual level. The way politics creates a context for and shapes intimate personal relationships is always present in his books and, in his most famous titles, it’s morality and sexual politics that are at the forefront as I pointed out in my earlier review of Time of Desecration.

This is true with 1934 too – but, sadly, I have to say that this can’t be counted as one of his most successful attempts to use sexual obsession as a vehicle for talking about politics. I think the problems start with the fundamental unlikeliness of the plot itself. It’s 1934 and a young Italian writer, Lucio, a man in his late twenties, is besotted with the idea of despair and spends much of his time thinking about the choice between suicide or accommodation with this existential doubt. He goes on holiday to try and resolve this dilemma and encounters an odd German couple – an older, unpleasantly beefy man and his wife, an enigmatic much younger red-head. A distinctly ambiguous relationship builds between them, with the Italian man certain that the woman shares his fascination with despair. Oddly, her husband seems to both condone the flirtation between the two and also to be insanely jealous. We also discover that the man is a Nazi supporter and, according to the enigmatic wife, ‘has blood on his hands’.

The tryst remains unfulfilled when the German couple return home but before she leaves the woman tells Lucio that her twin sister will soon be arriving at the holiday resort and that he should see her as object of his desires and that he wont be disappointed. This kicks off a second half of the novel full of ambiguities – is this ‘twin sister’ really just the original woman? Is he being played for a fool? Is this all a literary conceit?

I’m actually conscious that I’m making this all sound way more interesting that it actually is. In truth it’s all a bit muddled and rather pedestrian with the central premise – that this is all an extended metaphor for the relationship between Italy and Germany in the 1930s - really failing to take off in a way that casts any real light on the subject.

But before you run away with the impression that I’m damning it out of hand, it’s worth saying that this is Alberto Moravia after all and there are some passages of sublime writing and some intrigue that keeps you going – just about. But it has to be said that if you’re not already a fan of Moravia, this may not be the place to start because, like me, you’ll be left wondering what all the fuss is about when it comes to his reputation. The two I’ve now read have been a bit of a disappointment but I’m assured by all I’ve read that if you want to give him a whirl, your starting point should be The Conformists in order to get a fair sense of what he’s all about. So that’s my next stop somewhere down the line.

Terry Potter

December 2020