Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 14 Jul 2020

posted on 14 Jul 2020

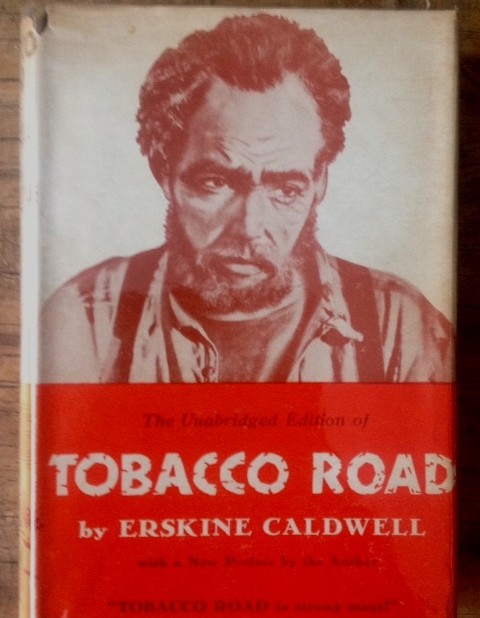

Tobacco Road by Erskine Caldwell

Setting a novel in the dustbowl of Georgia USA during the Great Depression of the Thirties really should give any reader a pretty strong signal that they are in for some pretty grim stuff. And that’s certainly what Caldwell serves up here – in spades. Where Steinbeck’s mountainous classic, The Grapes of Wrath, imparts a sort of timeless spirit and dignity to the forlorn lives of the small farmers and sharecroppers made a victim of distant economic forces they can’t really understand, Caldwell strips them down to their basics. There is very little of the transformative spirit here, the ray of hope for the human will to survive and build community; instead, we see humanity as essentially base and what survives is an almost animal instinct for survival and continuance.

As you might well imagine, the book’s publication in 1932 caused something of a storm, especially in Georgia where there were outraged cries of dismay at how the people of that land were being portrayed. Interestingly enough, it seems that the anger was prompted more by what was construed as the moral degeneracy of the Lester family and their associates and neighbours than about the shocking poverty and lack of education that underpinned their circumstances.

In a way, it’s easy to see why that happened: the Lester’s are without money or hope and seemingly without an identifiable future. Head of the household, Jeeter, is feckless and unable to see through any useful task that might earn the family a living. Essentially he’s given up on everything except for one thing – the idea that he will one day plant again and become a farmer once more. But we know that this small flame will never fan into a fire. The three generations of the family that he heads lives in a shack that barely stays upright and most of the children he has fathered have left to try and find survival elsewhere – knowing that to stay is to participate in a futile dream. He has just disposed of his youngest daughter, Pearl, aged just 12, to be the very reluctant wife of his immediate neighbour, Lov.

Two more children remain in the house: the 18 year old Ellie May who they can’t find a husband for because she has a cleft-lip that Jeeter, negligently and rather pathetically, has failed to ever get properly seen-to at the hospital and the 16 year old son, Dude, who becomes the predatory target of a middle-aged female preacher who wants to take him off as her new, latest husband. A sort of stew of simmering, unpleasant and exploitative sexuality simmers around these children.

Jeeter’s wife Ada and Grandma Lester also live in the run-down shack and along with Jeeter himself, all of them are obsessed with death in some form or another. It’s as if mortality is a train about to arrive at this particular station and the adults are constantly looking down the line waiting for it to arrive. When it arrives for all of them – Grandma through a grotesque accident at the hands of her grandson and Jeeter and Ada by fire – it’s almost with a sense of inevitability. However, it’s impossible not to feel that something of the tragedy that typified Jeeter’s life has passed to his remaining son, Dude, who, at the end, envisages himself farming the land that has yielded nothing worth having for years.

The book proved popular as something of a scandal novel, a piece of lurid pulp fiction to titillate. But I think that undercooks its literary merits. Caldwell is no Steinbeck it’s true, but he writes a compelling and engaging story that has within it a more complex set of messages than the average pulp shocker might seek to make. Caldwell was in the inter-war years a political writer and an activist who was concerned about the poverty of the South – although in later years, after the Second World War, his reputation took a hit when he drifted into the arms of the eugenicist movement, believing that it might be a solution to the problems he had been writing about. He wasn’t, of course, alone in that misguided belief in a repellent philosophy – take a bow Winston Churchill and George Bernard Shaw amongst others. But that does naturally put a somewhat different slant on Caldwell’s earlier writing for those of us reading the books now and one which might understandably turn modern day readers away from his work.

You won’t have trouble finding cheapish paperback versions of the book but don’t try reading it unless you’re feeling pretty emotionally robust…

Terry Potter

July 2020