Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 19 Dec 2018

posted on 19 Dec 2018

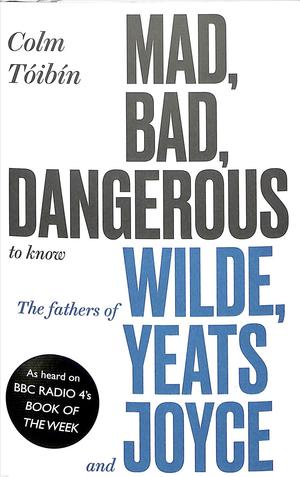

Mad, Bad and Dangerous To Know: The fathers of Wilde, Yeats and Joyce by Colm Tóibín

Tóibín's book has its origins in a series of lectures he delivered in the USA as part of an event to celebrate the life and work of the great biographer, Richard Ellmann. And, to be honest, that’s exactly what this book feels like – a series of loosely collected essays.

But I should also add that Tóibín is incapable of writing inelegant or uninvolving prose – whether it’s fiction or non-fiction – and each of the essays here has its considerable merits. But I don’t think his strength lies in the more formal end of the research process because when he’s drawing too heavily from other sources his prose becomes surprisingly stiff and flat. It’s only when he feels unencumbered by the historical heritage of secondary material that his own voice takes off to full effect.

That really is most obvious in the opening, introductory, scene-setting first essay which is about Dublin; he walks the present-day streets of the historical, literary and political Dublin and finds that even today it is still haunted by the ghosts of great writers and the events they witnessed. Here Tóibín is free to let his natural writing instincts loose and his capacity to conjure-up Dublin’s spirit of place is almost intoxicating. Sadly, it’s not until the final essay on John Stanislaus Joyce that we see Tóibín, again freed of the constraints of historical documentation, take flight again and really write to his strengths.

I also think there is some slight confusion over what the focus of the book is. At one level it’s obviously a book about fathers and sons – and often it’s a story of the distance between fathers and sons. But inevitably much of what gives these stories their interest is the fact that the son is a famous – even notorious – literary giant. So there is always something of a tension between whether Tóibín is trying to draw a biographical pen-portrait of the father as a legitimate subject in his own right or, through the study of the father, cast a light on the work of the son.

I have a suspicion that Tóibín was well aware of this tension and has tried to have the best of both worlds – and I’m not sure that it’s something he entirely manages to pull off.

Perhaps the most orderly and the most formal of the essays is the one dealing with Sir William Wilde and I think it’s also the least interesting. So much research and background on the Wilde family already exists (and is quoted extensively here) that there doesn’t seem anywhere new or different for Tóibín to go with his exploration. That’s not to say it’s not competently done and interesting to read ( and comparatively short compared to many biographical portraits) but you can’t help but feel there’s something a touch pedestrian about the essay.

John B. Yeats on the other hand is a far more interesting kettle of fish as far as I’m concerned and I certainly get the impression he interests Tóibín a lot more too. Yeats was an eccentric artist and an eccentric father in his own right and the fact that he effectively exiled himself in the USA for the most part of his life created an really fascinating dynamic with his famous poet-son. Their dialogue – influential on Yeat’s development as a poet – was almost entirely conducted by letter, as was a sort of long-distance, unrequited love affair with Rosa Butt who was the daughter of Isaac Butt, founder of the Home Rule League in Ireland.

However, the essay that sees Tóibín really come into his own is the one that takes on James Joyce’s father, John Stanislaus Joyce. There’s not a lot to detain us about Joyce senior; he was a moody, obnoxious, abusive drunk and if you want a portrait of what he was like to live with and what he meant to his children you can read the autobiography of his other writer son, Stanislaus Joyce, My Brother’s Keeper that is unstinting it’s vituperative assessment of the man.

What is much more interesting is the way the relationship between John Stanislaus and James found its way into the writing of the son. Tóibín is really excellent at plotting the transformation of the father into the fiction and he, at last, feels on really solid interpretive ground and free to put his own imprint on the relationship.

The book was abridged slightly and read on BBC Radio 4’s Book of the Week and, if you listen to any of the instalments, you’ll get a clear sense of how Tóibín constructed these essays originally as lectures to be read aloud. But there’s plenty here to read and enjoy too – especially if you have even a small amount of the passion the author clearly has for his subjects.

Terry Potter

December 2018