Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 30 Jun 2018

posted on 30 Jun 2018

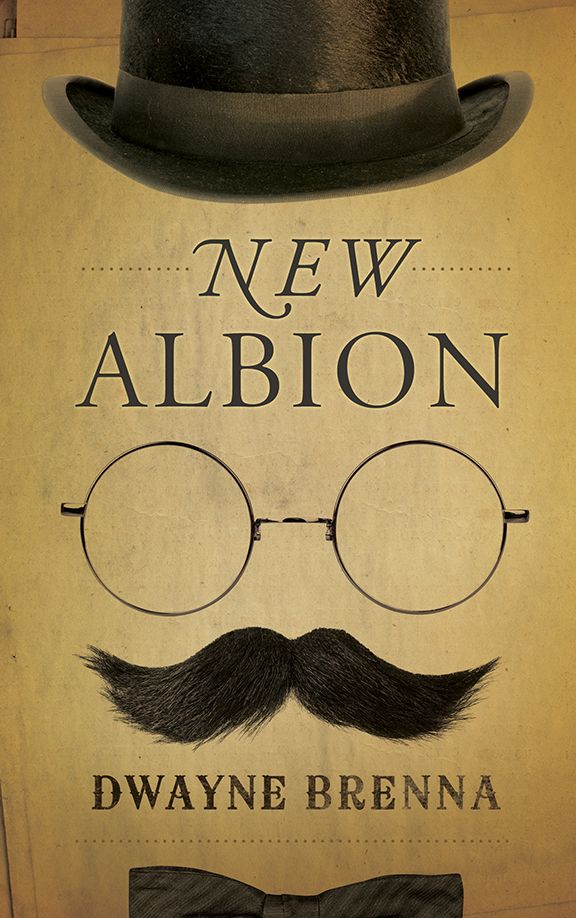

New Albion by Dwayne Brenna

For those of us raised on the easy accessibility of film, television, radio and, now, the internet and social media I think it’s hard to get your head around just how important the theatre was as a form of entertainment in the 18th and 19th centuries. The power of playwrights to speak directly to and influence the views of audiences that often spanned the class divide has long been understood and feared by government and by those who set themselves up as moral custodians of decency. As a result the theatre has often been the focus of censorship and repression and subject to strict controls in terms of what it was allowed to produce.

As the 18th century turned into the 19th, the tight control maintained on the number of London theatres allowed to exist was gradually relaxed to meet the growing demands of London’s booming population. By the middle of the century there was a thriving and colourful ‘theatre world’ dominated by relatively wealthy theatre owners who maintained both the theatre as a building and brought together a company of actors and writers who would keep a roster of plays constantly on the go. And it wasn’t a world dominated by highbrow theatrical aspirations – as the British Library website notes:

“In 1843, propelled by the Victorian urge to control and educate the new urban masses, Parliament finally changed the licensing laws and permitted all theatres to stage straight plays, hoping both to civilise the audiences and to encourage more literate modern playwriting to develop. The unexpected consequence was not more productions of Shakespeare, inspiring new Bards, but the growth of the West End, and the burgeoning of theatres and other, unpredicted forms of entertainment. Freed from restriction, the music hall and many other shows that were not strictly dramatic developed, to serve a large but divided audience with many different tastes and capacities to spend. The two old London playhouses, similarly dividing between high-brow and mass offerings, became venues for two kinds of musical theatre: the opera at Covent Garden, and a spectacular annual pantomime at Drury Lane alternating with sensational melodramas, reliant on stunts like a working paddle steamer or real horses racing on stage..”

It is in this crucible of theatrical change and ferment that Dwayne Brenna has set his novel, New Albion. Brenna takes us up close and personal into this world by using the mechanism of the private journal entries of the New Albion theatre’s upright, decent and rather anxious stage manager, Emlyn Phillips. The New Albion isn’t big and prestigious and its actors and writers have all seen better days or maybe will never see anything that remotely approaches a better day but Phillips’ diary entries effectively let us live through the machinations, the comings and goings, the ups and the downs of this theatre and its company as it sits slap bang in one of London’s most notorious working class districts in the months from September 1850 to February 1851.

The timeframe is important here because it’s the lead up to the theatres most important time – the Christmas pantomime, when it can expect to draw the big audiences that will keep it going for the rest of the year. Brenna serves up farce, gentle humour, catastrophe and stories of personal tragedy as the colourful company fall out, make up, get drunk, get pregnant, develop animosities and make a complete mess of most things. But, despite this, somehow they stay together and somehow the play must go on.

Providing us with a specific character, Phillips, to navigate us through the increasingly fractious events leading up to December is quite a risky strategy for a writer to adopt because he’s really gambling on the idea that we will like and trust the narrator. Fortunately, Brenna’s been skilful enough to pull this off – Phillips is generous, has a moral compass and is reliable enough for us to throw our metaphorical arm around his shoulder and go with his take on things.

Using the journal entry device inevitably tends to break the book into a series of anecdotes but I don’t see that as a problem – like the best epistemological novels, the thread that holds it all together is robust enough to bear the weight. What I really came to like and admire in the book however was the creation of character – I really did come to care about them.

Phillips aside, there are some rich and enduring creations here: the clapped out, laudanum addicted stock writer, Mr Farquhar Pratt who is on a path of self-destruction; theatre owner, Mr Wilton who has brought the place for the vanity use of his wife; their daughter, known by her stage name, the Parisian Phenomenon; and the roguish and unpleasant, Colin Tyrone who becomes the villain of the piece. Great creations all with potential back stories that, if explored more fully, could have turned the book into something as big as the novels of that period.

Although the book is based on and inspired by true stories, that background doesn’t really matter – it’s not, I don’t think, a fictionalised account of a real set of circumstances but an imaginative recreation of a world now lost to us. In the same way that Sarah Waters’ Tipping the Velvet was able to take us inside the Victorian world of the theatre, so on a more modest scale Brenna has done the same – and an informative and enjoyable trip it was too.

Terry Potter

June 2018