Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 22 Jun 2018

posted on 22 Jun 2018

A Room With A View by E.M. Forster

I have to say at the outset that E.M.Forster’s A Room With A View is not the kind of novel I’d normally be revisiting. I did read it when I was at university and I pretty much dismissed it back then as a bit of fluff. I don’t think this was just the arrogance of youth – although I suspect that was a big part of my casual dismissal. I can remember writing a term paper about how Forster had written something that amounted to little more than cheap romantic fiction.

Even allowing for the hope and expectation that my critical appreciation has matured over time, picking this up again now would not have been on my agenda had it not been for another bit of serendipity. Browsing the shelves of a charity shop the other day I came across a mint copy of Sheila Rowbotham’s biography and critical appreciation of Edward Carpenter. Intrigued – largely because I knew virtually nothing about him – I bought the book and took it home to browse through.

Carpenter (1844 – 1929), it turns out, was a truly fascinating character who was a radical free-thinker, Socialist, gay rights campaigner, advocate of free love and of women’s rights. Name a radical cause and it seems like he was into it. He was also networked to the gills – he knew everyone who was anyone on the intellectual Left. His Wikipedia entry captures this succinctly:

“A poet and writer, he was a close friend of Rabindranath Tagore, and a friend of Walt Whitman.[2] He corresponded with many famous figures such as Annie Besant, Isadora Duncan, Havelock Ellis, Roger Fry, Mahatma Gandhi, Keir Hardie, J. K. Kinney, Jack London, George Merrill, E. D. Morel, William Morris, Edward R. Pease, John Ruskin, and Olive Schreiner.”

To say that Carpenter was anti-establishment and dismissive of convention would be to massively understate his philosophy. His scorn for what he saw as a bankrupt social morality wasn’t just a stance he advocated for others – he lived his politics and was in a long term gay relationship with a Sheffield working man, George Merrill.

And this is where Forster comes back into the story because Carpenter, Merrill and Forster were good friends and spent a lot of time together. Carpenter’s politics and social attitudes had a huge influence on Forster as a writer and contributed directly to the message at the heart of his early novels – including A Room With A View.

The story of Lucy Honeychurch and her liberation from the potential stifling web of Edwardian conventionality is indeed as simple and undemanding as any romantic comedy of manners – hence the popularity of the Merchant Ivory film of the book – but seen from the perspective of Carpenter’s influence on Forster, it takes on another, I think more interesting dimension.

Lucy is a young woman full of potential passion for life whose only outlet for this aspect of her spirit is music – she plays the piano with a verve that unnerves the parlour decorousness of her surroundings. Her natural inclination towards free expression is constantly being curtailed and confined by the petty and unfathomable ideas of what is deemed ‘appropriate’ by her elders and by social etiquette. While on a chaperoned holiday in Florence she encounters the Emerson’s – an older father and his son, also of Lucy’s age. The Emerson’s don’t conform to the establishment idea of what constitutes decorous behaviour and have a habit of speaking their mind and doing what feels right. Lucy finds herself drawn to them both – although she struggles at first to reconcile her feelings for the younger George Emerson, especially when he kisses her and the kiss is witnessed by the chaperone.

Such a terrible social faux par leads them to leave Florence for Rome where Lucy meets up again with Cecil Vyse, a young man who is seeking her hand in marriage. Vyse, however, is in many ways the antithesis of both Lucy and George. He’s judgemental, priggish, conceited and constantly critical of the intellectual capacity of the decent, ordinary people he meets.

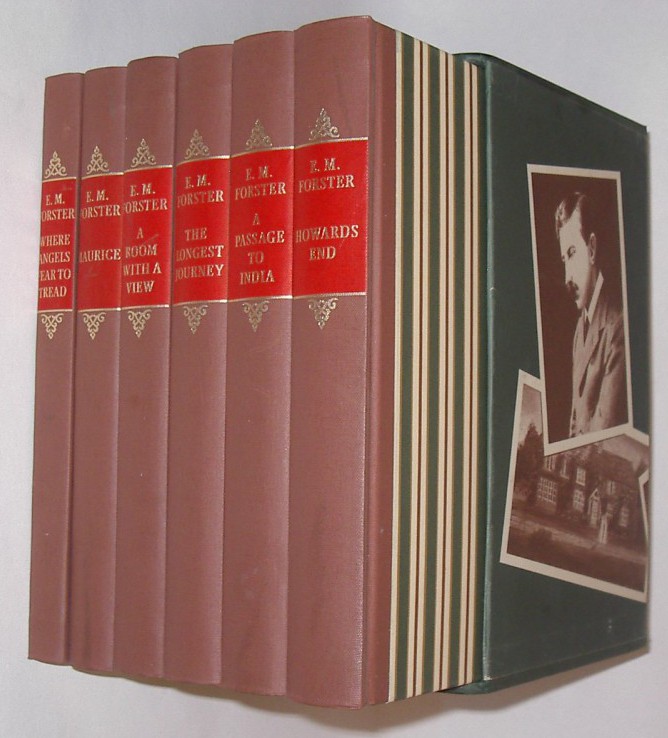

It’s not hard to guess how this plays out. In the end Lucy rejects Cecil and the promise of the conventional – and unhappy or unfulfilling - life he offers in favour of a relationship with George. The book ends happily and my Folio Society edition also reprints Forster’s three page Appendix written in 1958 in which he speculates on what kind of lives Lucy and George end up living.

I’m not sure that my original assessment of A Room With A View was a million miles wrong – this is essentially an undemanding romantic comedy in many ways. What does lift it above that however are a couple of things: firstly, the underlying philosophical direction the novel takes and, secondly, the quality of the writing.

It is often the case that the most effective critical or satirical writing about the middle classes comes from within – Evelyn Waugh, Anthony Powell and Forster do such a good job of picking apart the constipated and hypocritical mores of their class because they understand it from the inside. Introducing into that world the ‘virus’ of ‘Carpenterism’ in the form of the Emersons is the catalyst that highlights the absurdities and destructiveness of the dominant middle class conservatism. It's also clearly the case that Forster's own frustrated sexuality and desire to break free of convention informs the book throughout. His own sublimated desire find a fulfilling gay relationship has been poured into the character of Lucy and the happy ending she is given is obviously wish fulfilment on Forster's part.

The writing style is hugely entertaining though - it's waspish, constantly sardonic and with a sharp eye for the absurd. This isn’t the style that produces belly-laugh moments but much more that which is associated with Austen, Trollope or Thackeray – a satire of the socially absurd.

So, did I like the novel more than first time around? Well, sort of but not enough to make me think I’d horribly misjudged the book all those years ago. I still think it’s largely light-weight but I can see that a bit of historical social and philosophical context gives it an added dimension.

Terry Potter

June 2018