Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 17 Jun 2018

posted on 17 Jun 2018

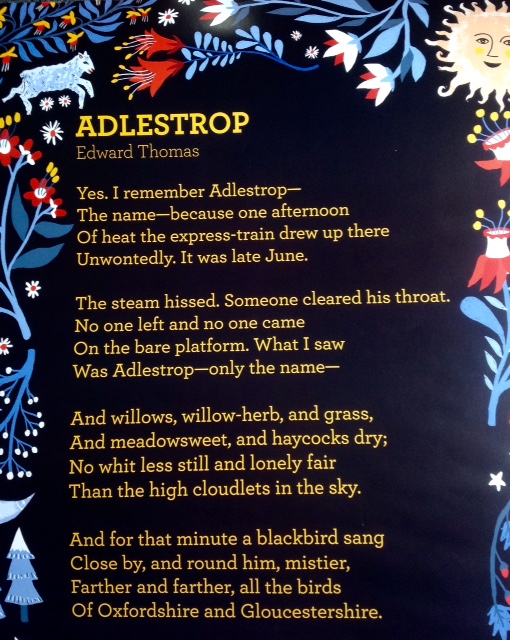

The enduring appeal of Edward Thomas’s Adlestrop

"Yes, I remember Adlestrop --

The name, because one afternoon

Of heat the express-train drew up there

Unwontedly. It was late June.

The steam hissed. Someone cleared his throat.

No one left and no one came

On the bare platform. What I saw

Was Adlestrop -- only the name

And willows, willow-herb, and grass,

And meadowsweet, and haycocks dry,

No whit less still and lonely fair

Than the high cloudlets in the sky.

And for that minute a blackbird sang

Close by, and round him, mistier,

Farther and farther, all the birds

Of Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire. "

Not so long ago I was paying a visit to the excellent independent bookshop, Jaffé and Neale in Chipping Norton and while I was there I picked up the beautifully designed poster of Edward Thomas’s popular poem, Adlestrop. The poster cost me a small donation to a charity fund raising effort and I wasn’t the only one in the brief time I was there who was happy to dip into their pocket to take one away with them.

Thomas’s poem was recently voted Britain’s 20th favourite of all time and although I acknowledge the fatuous nature of these polls, I do think it’s a useful indicator that this poem has entered deeply into the poetry-readers psyche. The question is, why?

The poem concerns itself with a seemingly mundane event as on a late June day in 1914 Thomas was making his way to visit Robert Frost in Ledbury, travelling on the Oxford to Worcester train. The train makes an unscheduled stop at the station of Adlestrop in Gloucestershire (which was closed in the Beeching railway service cuts of the 1960s) and sits for a while before departing again.

Hardly an event at all you might think and in many ways that’s true because this is a poem about nothing happening. But, importantly, that ‘nothing’ happens in quite a particular context. You might jump to the conclusion that Thomas knocked this poem off either at the time he was sat staring out of the window or immediately after the train journey but that wasn’t the case. He did in fact work on it for some time afterwards using observations he made in his nature notebook as the train sat briefly in the station. And what this tells us is that the poet in Thomas knew exactly what he was doing by loading this seemingly trivial event with its many layers of potential interpretation.

Although this is not a conventional Great War poem, many anthologies now include it as a meditation on a world that has been lost forever – a still moment before the horrors of the trenches and the slaughter that would change the world irredeemably. There is undeniably something elegiac about the tone that speaks its silent sub-text about a sleeping Edwardian Britain that has no concept of what is coming over the horizon to destroy the seemingly timeless values of this country’s metaphorical high summer.

While I think this is a powerful interpretation, there is another that is for me just as meaningful and less to do with the great world order and more to do with the individual and what some might refer to as the ‘spiritual’ or ‘mystical’ – although that’s a language I don’t personally like. I think there can be very few people who haven’t had the experience of time suspended, a moment when the world around you stops and a sense of huge well-being descends on you, uncalled for and unexpected. It is at moments like that when it’s possible to understand the poetry of Henry Vaughan, Wordsworth’s Pantheistic urge or the Buddhist notion of oneness. But it is only ever fleeting and is often triggered by the mundane. In many ways this is an undefinable feeling beyond the reach of words but in Adlestrop, Thomas has captured that moment by not trying to pin it down or make it explicit.

I think that the poem is also tinged with a sense of mild concern and regret at the inevitability of change. It’s no coincidence that Thomas was on an express steam train which, as the paintings of JMW Turner had shown in the 19th century, is an effective symbol of unstoppable progress and the speeding up of everyday life. And it’s this unexpected stop in the journey that gives the poet a chance to draw breath and to really look and listen – it provides an interesting echo of the earlier W.H.Davies poem, Leisure, in which the reader is asked the rhetorical question:

“What is this life if, full of care,

We have no time to stand and stare.”

It’s also the case that although this is a very short poem, it’s impossible to read quickly. When I unroll the poster – which I’m planning to frame – and look at it, I still find myself drawn onto that train, captured with Thomas in that momentary bubble and through the window are the parks and playgrounds of my childhood and the birdsong of my past echoing down all the days.

Terry Potter

June 2018