Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 03 Mar 2018

posted on 03 Mar 2018

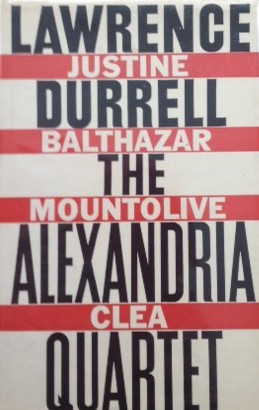

Justine by Lawrence Durrell

I’ve got a chequered history when it comes to this novel. When I first read it back in my early twenties I was mesmerised by what seemed to me to be a dazzling display of daring writing and experimentation and it made me plough on through the next three novels – Balthazar, Mountolive and Clea – that make up what is now commonly known as the Alexandria Quartet. Indeed, it was Durrell’s intention that the books should all be read as one event despite the fact that they came out individually over a three year period between 1957 and 1960. In truth, however, I never felt anything he wrote after Justine quite reached the dizzying heights he achieved in the first instalment.

When I read it again – probably in my late thirties or early forties – I found myself astonished that I’d been so easily impressed. It seemed to me on this reading to be a hollow thing, all dazzle and no real substance, verbose and irritatingly mystical. I hated the characters I’d once thought so wonderful and I couldn’t help but feel that if I’d personally known Justine herself I’d have given her a ticket to anywhere that’s as far away from me as possible.

Now, another two decades later, I’ve come back to it again and at the risk of sounding annoyingly like a Liberal Democrat politician, I think I find myself agreeing with both my earlier judgements – to a greater or lesser extent. Justine is, I think, a pretty brave attempt at reimagining the structure of the novel and although he’s clearly influenced by the likes of James Joyce and Henry Miller, he does capture a sort of prose Impressionism in his constructions. Perhaps I’d go even further and say that it quite often feels to me that whilst the Impressionist label works well for the creation of the landscape – the city of Alexandria is in some ways a bigger character here than the people who populate it – a better artistic analogy for the characters might be Cubism. Our nameless narrator moves between times and dates, between his own narrative and that of others and between the real and spiritual in ways that construct portraits of people much as Picasso or Braque might have constructed their multiple viewpoints of the same objects.

Talking about the plot of the book feels essentially pointless. At the mundane level it’s about a classic love triangle (actually it’s probably better called a love rectangle in this case) and about what this does to our rather down-at-heel school teacher cum writer who retrospectively tells us the story of his infatuation with Justine, a mysterious and alluring Jewess who is married to a wealthy Egyptian Copt. In pursuit of the romance they embark on secret liaisons at the expense of her marriage and the narrator’s relationship with Melissa, a local exotic club dancer and someone who is pretty much everything Justine isn’t – grounded, kind and empathetic.

There is a cast of characters that are often brilliantly drawn and in the later books they will give an account of the same circumstances but from a wholly different perspective. It’s sometimes in the drawing of these other players that I think we see just what an extraordinarily good writer Durrell could be. When the narrator is invited to become a sort of secret service recruit for the British, he’s drawn into this by Scobie who Durrell describes in this way:

Frankly Scobie looks anybody’s age; older than the birth of tragedy, younger than the Athenian death. Spawned in the Ark by a chance meeting and mating of the bear and the ostrich; delivered before term by the sickening grunt of the keel on Ararat. Scobie came forth from the womb in a wheel chair with rubber tyres, dressed in a deer-stalker and a red flannel binder. On his prehensile toes the glossiest pair of elastic-sided boots. In his hand a ravaged family Bible whose flyleaf bore the words ‘Joshua Samuel Scobie 1870. Honour thy father and thy mother’. To these possessions were added eyes like dead moons, a distinct curvature of the pirate’s spinal column, and a taste for quinqueremes.

I think this is really superb stuff but, equally, it seems he’s unable to curb his desire to over-elaborate, to layer words on words and to use a lexicon that looks much too much like simple showing off. It’s just plain exasperating when you find yourself in a seemingly endless trill of words that look like they’re there just because he was determined to use them somewhere.

Most reviews you’ll read will almost certainly say that the star of this book and the others that make up the quartet is the city of Alexandria itself. At the time Durrell was writing about it the city was a classic melting pot of Arab, Jewish, British, French influences and it’s a tribute to Durrell’s skill that the sights, sounds and smells of the streets come alive in these pages. It’s both a love letter to the city and a kind of appalled retrospective that perfectly captures the way people get bound up in the spirit of certain places.

Did I enjoy reading this again? Yes, I can honestly say I did but I can also honestly say that it’s a deeply flawed piece of work. Not that I mind that. He’s trying to do stuff here that deserves praise even when it doesn’t come off and in this review I haven’t even touched on some detail and themes that almost merit books in their own right – the musings on the Kabbalah for example – which show the scope of his ambition.

Will I go on to the rest of the Quartet now? No, I don’t think so – not yet anyway. There’s too much competing stuff that needs reading and this experience, enjoyable enough, didn’t feel sufficiently essential to dedicate more time to.

Terry Potter

March 2018