Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 18 Feb 2018

posted on 18 Feb 2018

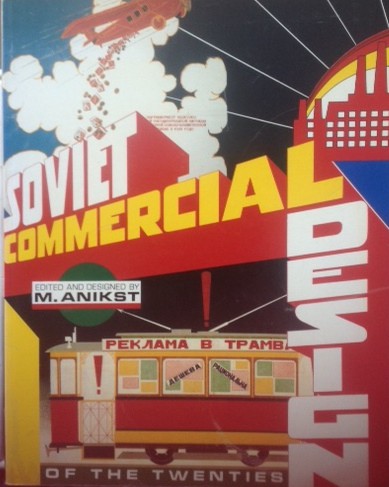

Soviet Commercial Design of the Twenties edited and designed by Mikhail Anikst

I’ve always been a huge fan of Soviet avant-garde art of the 1920s and 1930s and I especially like the poster art that emerged as part of Government-led information campaigns, propaganda or cultural events. The posters designed for the film industry are simply superb and so many modern day designers still draw on the work of this period for inspiration.

What I’ve never really given any thought to is the way in which this movement became central to Lenin’s ideas for a New Economic Policy – that would, all too soon, run into the sand. Art linked to the industrial future was the vision for these designers and what became known as Constructivism leaked across into commercial graphic design and resulted in ephemera that was fabulous to look at. Examples of cigarette packets, sweet wrappers, match-boxes and packaging of all sorts are here – if you had the money to buy the products that is. And here is the rub; this was a time when the working people for whom this art was meant were barely able to feed themselves let alone buy any luxuries. So, inevitably, it was those in the most powerful and influential positions who ended up benefitting most from this flowering of public art.

Elena Chernevich writes most of the text here – both the main essay and the ‘vignettes’ as she calls them - but it’s Anikst’s design and editorial that really catches the eye. Anikst, who is in his late 70s as I write this, is himself a noted commercial design artist and worked in the old Soviet Union and so comes to this enterprise with a wealth of information and knowledge of the subject. He’s uncovered examples here that have never before been published and he turns them into a visual feast.

In the introductory essay, Chernevich sets out her case:

When compared to European work of that period, let alone European work today, Soviet Constructivism looks coarse. It is built of straight lines. It does not explore the whole typographical palette, and it is useless to seek such range in it. But that is precisely the cause of the strong image which it projects – the image which so firmly imprinted innovative principles and attitudes on the wider professional consciousness…Constructivism prepared the soil on which more refined products could grow thereafter. Even today, typography the world over derives nourishment from the ideas of the twenties, and many of those ideas derive directly from the Soviet Constructavists.

It has become a kind of received wisdom that this period of Soviet art was in some way ‘crude’ but this is something I just can’t go along with. To me these images are powerful, sophisticated and make much of the minimalist design of the late 80s and 90s look pale and uninteresting. I see Constructivism as the perfect example of how art relates to the society from which it emerges and this was clearly a society that, despite all its problems, was one full of vigour and optimism.

You can find copies of this book, originally published by Thames and Hudson in 1987, available in paperback on the second hand market for under £15.

Terry Potter

February 2018