Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 01 Nov 2017

posted on 01 Nov 2017

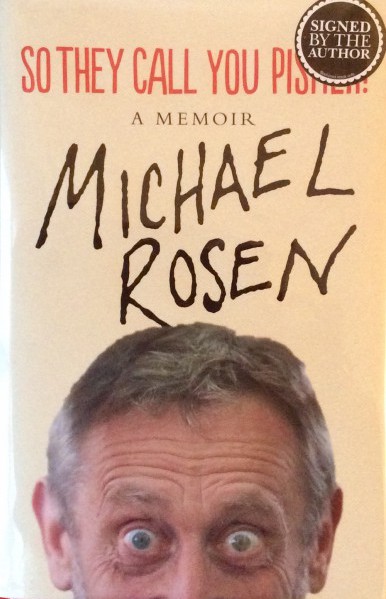

So they call you Pisher by Michael Rosen

I have always been impressed at the scope of Michael Rosen’s career so far and wondered how on earth he manages to be a BBC radio presenter, Children’s Literature academic, linguist, Guardian column writer, political campaigner and prolific writer of marvellous children’s poetry and fiction. I have also seen him perform at various events and conferences and been fascinated at how he throws himself fully into the entertainment, which he evidently enjoys tremendously. Where does he find the energy and space in his head to juggle all these many components and yet still appear to be very affable and well adjusted? By reading this autobiographical book I at last feel that I have had a glimpse into ‘How to grow a Michael Rosen’.

I don’t usually read autobiographies but picked this one up feeling fairly certain that I would enjoy it. It is packed full of splendid anecdotes, a few of which I have heard before, although this didn’t matter one bit. He tells the story of how his mother Connie and his father Harold met and ended up living in the North London suburbs and how they brought up himself and his brother, Brian all written in a tone that has real affection and some self-deprecation. It seems that both children were stimulated from their earliest days to soak up culture, language and politics. Michael’s distinctive voice gives us an array of often funny and poignant family stories that present family members, friends, school and just about everything as a kind of theatre

We are all shaped by the religious and political views of our parents, whether they appear to be non–existent, mild or keenly defined like the Rosens. Harold and Connie, both teachers first met as teenage Communists in the Jewish East End of the 1930s and remained active party members until 1957. Michael’s childhood was one that had a constant backdrop of political meetings and debate and he realised that his home life was rather different to those of his school friends. I liked the way in which he reflects on his gradual awakening to his identity and his puzzlement in untangling what was and wasn’t part of being a Communist; for example, ’No one in my school went camping. They stayed in boarding houses. In the first years we went camping, we went with Communists. That was how I worked out that camping was Communist’.

And there are plenty of clues about how he came to notice and to love words in his reminiscences of conversations peppered with Yiddish and on-going gags from his father. The magic of vocabulary associated with particular experiences is returned to over and over – this is surely the early life of a poet. Of course he is writing retrospectively and perhaps didn’t focus quite so much on these words at the time but the fact that he can conjure them up with such relish seems significant. It seems that books were always important in his life. His memory of Harold reading ‘Great Expectations’ aloud on a family holiday using voices for all the characters tells us all we need to know about the importance of stories:

‘I got that Harold and mum loved this story, Harold in particular. The way he read it with such passion showed that he loved it more than any of the other hundreds of stories on the shelves at home, more even than the plays at the theatres we went to.’

Later he explains how his father, when studying for a PhD was immersed in academic books and this meant that his family was as well because he shared his reading aloud whether they liked it or not:

‘Ghostly figures form the world of linguistics, literate theory and philosophy loomed up into our kitchen and front room without any of us knowing exactly why’.

I could tell you much more about other significant episodes in the first twenty three years of his life including his desire to be French, his journey to Aldermaston to march against the bomb aged just thirteen, the moment he realised that he wanted to write poetry for children, going to medical school (which was a decidedly wrong fit), and how the Cuban Missile crisis woke him up to world politics. However this is a big hearted book that you need to read and revel in for yourself because Michael Rosen is a master storyteller. I promise that you won’t be disappointed.

Karen Argent

October 2017