Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 15 Jul 2017

posted on 15 Jul 2017

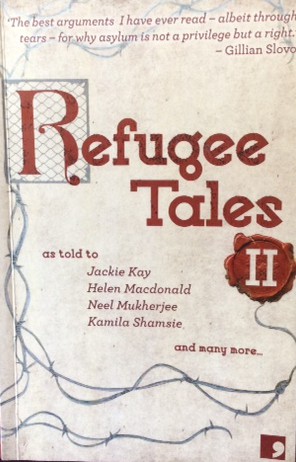

Refugee Tales II as told to Jackie Kay, Helen Macdonald, Neel Mukherjeee, Kamila Shamsie and many more

This is the second volume of stories told by asylum seekers to poets and novelists , a format that is inspired by The Canterbury Tales. This is a way of knitting together individual experiences with a common theme. I have already reviewed the first volume of stories written by an equally fine selection of authors which can be found on this link .

Once again I have the dilemma of which of the eleven tales to tell you about, because all have their merits and are equally powerful. For instance the first one in the collection is The Students Tale by Helen Macdonald captures the horror of an individual being regarded as a dangerous disease because of holding religious beliefs:

‘They want to isolate it, contain it, and like all such malevolent metaphors that equate morality with health, the cure is always extinguishment’

Macdonald listens to the gentle, at first reticent young man who was a student of epidemiology in his home country who refuses to be defined by his vulnerability and tragic recent past because he tells her that wants to get on with his life:

‘I want to quickly take a part in this society. And the culture. … I think my living is very precious.’

The Lovers Tale by Kamila Shamsie tells us about how a boy has had his childhood and youth forever scarred by being forced by a political regime to become involved in betrayal and murder. The catalogue of misery in this story is relentless and made all the more difficult to read because of being so understated. The shape of the story is also significant because every time it seems to reach a climax, the author reminds us that it isn’t the end of the story which means that the reader immediately steels themselves for the next episode. Along the way he meets and falls in love with a young woman, the sweet memory of a relationship that he clings to throughout the next few terrible years. After periods of unspeakable torture and several failed attempts to escape from his country he is able to seek asylum in the UK and the story has a positive ending with the eventual reunification with his lover and their three children. The man telling the story is clearly deeply traumatised and needs to tell it as a cathartic act, even though he has obviously told parts of it many times before as a necessary part of his asylum seeking process. But the story isn’t over because we learn at the end that he is the only one of the family who has recently been denied indefinite leave to remain in the UK because he spent a period of time in prison due to working illegally:

‘The system is a bit …’ He doesn’t have the words, and neither do I. ‘ I don’t understand it’.

I liked The Barrister’s Tale by Rachel Holmes with its focus on the need for a human rights lawyer to stay sane and grounded within her own family in order to be able to fight for her many clients. So this story has a distinctive shape that begins and ends with her spending pleasurable time with her child. The middle part of the tale includes a close examination of legal terminology used in the asylum process. In trying to explain the complexity of preparing a case the lawyer reflects on the surreal nature of telling people the imprecise nature of their asylum status:

‘Waiting indefinitely to be removed imminently. It’s like Becket and Orwell met for a bender on Bloomsday in The Kafka’s Head’

The Support Worker’s Tale by Josh Cohen has an interesting structure mostly written as fragments of what had been observed over many decades of working as a volunteer in a synagogue project for destitute asylum seekers. The Support Worker remembers many uplifting moments amidst sorrowful circumstances and the sheer variety of individuals that he has met who just want to come along to the project, be sociable and to feel ordinary. In contrast, the final section is written as a long stream of consciousness that for me effectively conveys a suffusion of solidarity, warmth and humanity.

Every poet and author brings a distinctive tone to the story they are sharing and The Smuggled Person’s Tale by Jackie Kay is particularly well told, perhaps it resonates so strongly with me because I am a fan of her other work. In the opening paragraphs she paints a vivid picture of a young man from Afghanistan who has made a long dangerous journey across several countries:

‘You could measure the distance in the look that crossed his face as he crossed the threshold into her house.’

I really loved the way that his written story, apparently mislaid, becomes an injured bird found in the author’s dark cellar. He brings it into her kitchen and cradles it tenderly as he recounts his experiences for her:

‘He looked into the eyes of the beautiful brown bird. He didn’t know it’s name. A thrush. It was a song thrush without a song. He was its song. He considered the bird’s dark dark eyes. They were like onyx or jet, moist and deep as the soul of a river. And because he felt welcome, he could at last take his time’.

There is an informative afterword that provides detail about the campaign that calls for an end to indefinite detention and how the annual Refugee Tales physical walk across southern England contributes to raising awareness.

‘Real as the walk is, and acutely real as are the experiences presented in the tales, there is a significant sense in which Refugee Tales is also symbolic. What it aims to do, as it crosses the landscape, is to open up a space; a space in which the stories of people who have been detained can be told and heard in a respectful manner. It is out of such a space, as the project imagines, that new forms of language and solidarity can emerge.’

I wish that I could write more here to encourage you to read all these inspirational stories – what a fantastic project that so successfully marries all those involved with the Gatwick Detainees Welfare Group with the writers and those who shared their tales.

Karen Argent

July 2017