Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 19 Mar 2017

posted on 19 Mar 2017

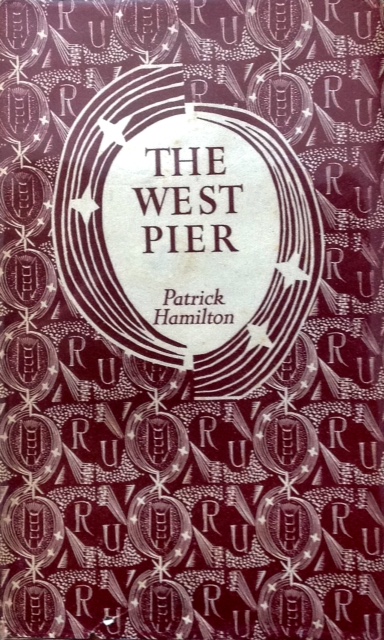

The West Pier by Patrick Hamilton

The West Pier (1952) turned out to be the first of a trilogy of books featuring the truly obnoxious Ernest Ralph Gorse, confidence trickster and borderline sociopath. The book garnered plenty of praise when it was published and Graham Greene called it ‘the best book written about Brighton’ which, given his own stake in that territory, represented quite a considerable accolade.

Hamilton, also a notable playwright as well as a novelist, has a remarkable feel for dialogue and in The West Pier he uses this talent to beguile the reader when, in fact, nothing very much happens over the course of the 250 pages. This is essentially a simple story – Gorse and two old minor public school friends go on holiday in Brighton to mark the end of their school days. They encounter two local 18 year old working class girls – one deemed ‘plain’ or even ‘ugly’ by the young men and the other an outstanding beauty who turns out to have a considerable sum of money saved and kept in cash in her bedroom. One of the boys, Ryan, falls in love with the beauty, Esther, while Gorse falls for Esther’s money.

What the novel plays out is Gorse’s detailed and completely unscrupulous campaign to poison the ground for Ryan and to inveigle and insinuate his way into Esther’s trust and affection in order to rook her of her money. This he does with aplomb and utter relish and Hamilton makes it clear that Gorse does this and ruins the life of a vain but honest working class girl just because he can and for the sheer frisson of being evil.

Much of what happens in the book is the result of social attitudes and relationship rituals that now might strike the reader as antiquated. The casual sense of privilege the visiting boys display and the naivety and seeming gullibility of the working class characters is hard to switch on to – there are a number of times when the readers credibility is stretched to the limit in accepting the unfolding plot Gorse hatches without any seeming barriers inhibiting his most Machiavellian plans.

However, the strength of the novel lies in the menacing and amoral shadow cast by Gorse. He’s a great creation – in some ways a natural sidekick of Patricia Highsmith’s Ripley – and the most anti of anti-heroes. From the very beginning when we see him in his school setting learning how to love mischief-making just for its own sake it’s clear we are in the presence of someone capable of real malice. And Hamilton gives us plenty of clues about Gorse’s willingness to do whatever it takes to pursue his own ends regardless of the damage he does – in fact, the more damage he does the more he likes it.

This is also a book about social class – three middle class boys come into the lives of two working class girls and, in their own way, exploit them in a casual way knowing they can ultimately turn their backs on them and walk away despite having created distress and havoc. But it’s also a book of place – Brighton and the pier are in many ways characters themselves. The traditions of the British seaside ooze from the pages of this book and casual dalliances on the boards and in the amusement arcades is as tangible here as the smell of candy floss, the flash of neon and the ching of the one-arm bandit slot machines.

I really enjoyed this book and ultimately found it compelling but Hamilton has a style that takes a bit of getting into. However, once you’ve acclimatised to his bold and quite unorthodox sentence construction and his habit of interjecting himself as a kind of dramatic chorus into the plot, it becomes unputdownable.

Terry Potter

March 2017