Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 09 Nov 2016

posted on 09 Nov 2016

Looking at John Berger

The great essayist, radical, art critic, novelist, artist and storyteller John Berger has just celebrated his 90th birthday. The BBC marked this with a short and rather fine film called “John Berger: The Art of Looking”, directed by Cordelia Dvorák. It has also been marked – as ever – by the publication of new books drawing together his now vast archive of writings on art and artists: Landscapes: John Berger on Art, and Portraits: John Berger on Artists, both published by Verso.

For a man so steeped in text and in the act of looking, reading, and writing, Berger’s name is perhaps oddly linked with television, through the groundbreaking Ways of Seeing from the very early-70s. This was not just a programme but a way of programme-making – and of thinking about and looking at art – that helped form the intellect, the mental furniture, of a generation.

I first began reading Berger in 1973, I think. I read Ways of Seeing, of course, but it is his wonderful collection of early essays, Selected Essays and Articles: The Look of Things (Pelican 1972) that I return to as to a time-capsule of sorts. The look of it, the feel of it – everything about it reawakens in me the feeling of excitement and bemusement that I had on first reading his work, these feelings running alongside a level of personal ignorance that seemed insurmountable. But that didn’t matter – because Berger, perhaps more than any other writer on the arts, society and culture, made me want to understand, no matter how hard it might be.

Berger now loathes the term ‘art critic’. They are, he says, pains in the arse – although not as bad as art dealers – and for himself prefers the designation ‘storyteller’. And certainly, everything he has written – in whatever form – does seem part of a bigger story.

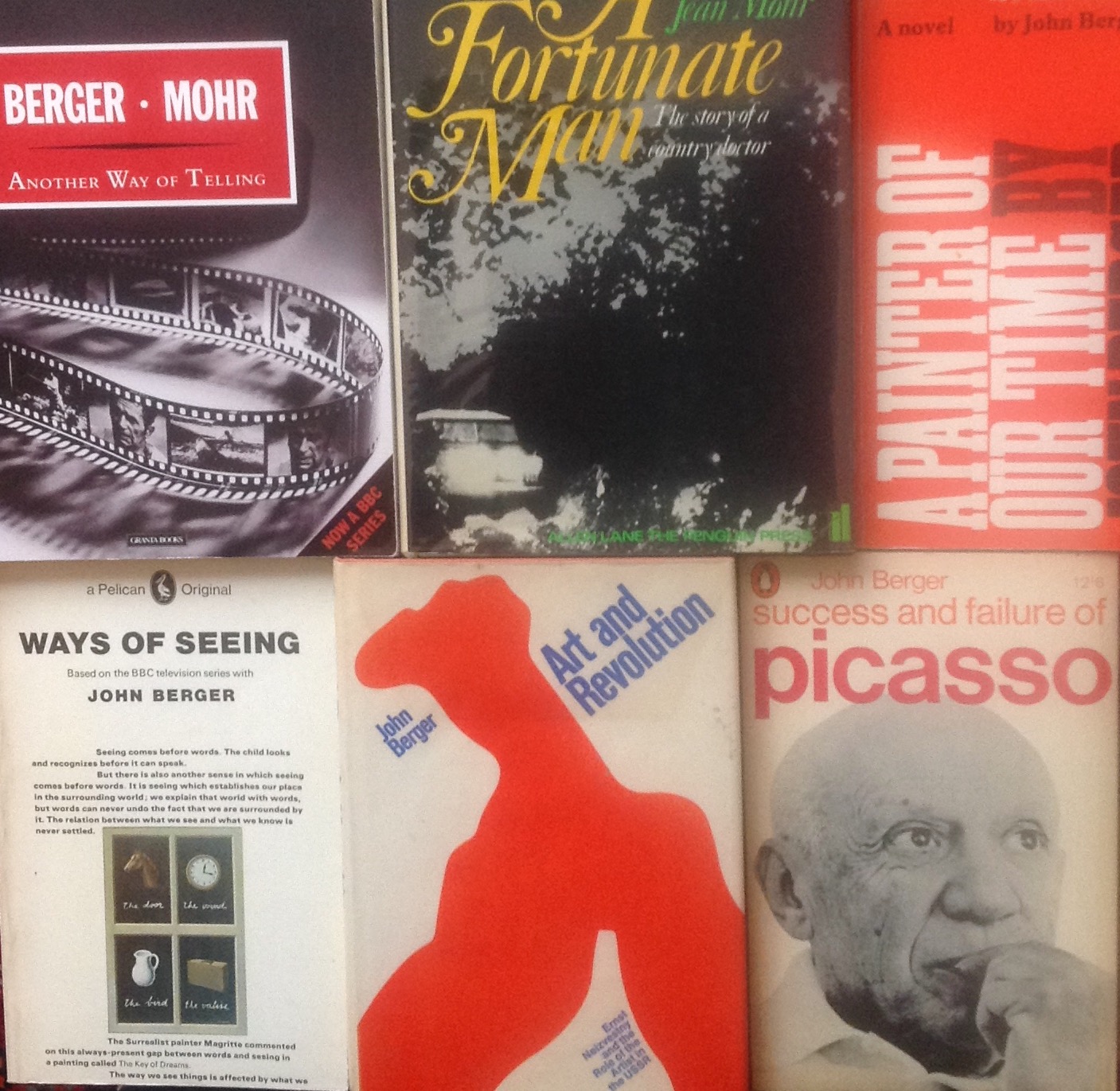

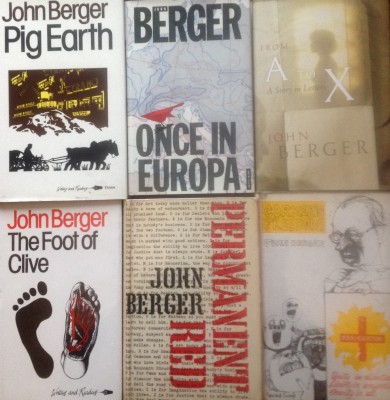

Despite this, he did make his name initially as an art critic – moreover, a radical, iconoclastic Marxist art critic, a sort of angry young man of the art world, I suppose. He scandalised the establishment when his novel G. won the Booker Prize in 1972 and he gave half the money to the Black Panthers. Disillusioned with life and politics in England, in the mid-70s he moved to the small village of Quincy in Haute-Savoie, where he began to farm a smallholding and document the life of agrarian peasants in a series of works including the novel trilogy, Into Their Labours. These can be seen very much as a study of the powerless, those whose dignity resides in the disappearing world of their labour, reflecting Berger’s long political and humanist interest in social groups outside the conventional consumerist structures of late neo-liberal capitalism. His finest books to my mind are those of the late-60s that he did with the photographer Jean Mohr, A Seventh Man, about migrant workers, and A Fortunate Man, about the life and work of a country doctor.

Cordelia Dvorák’s film is revealing because in it Berger talks about his relationships with other people. He refers to himself as a ‘solitary’, a storyteller, always on the lookout for other outsiders, sympathetic individuals who share a view, a complicité, with whom one can exchange an understanding wink that says, “We know, you and I – they haven’t entirely tricked us yet.”

Interestingly, the term he doesn’t use – but the one I would have most associated with him and most expected him to use – is ‘comrades’. For decades it has seemed to me that Berger has a small circle of sympathetic collaborators and colleagues, sort of cultural comrades. Comrades in what exactly it would be hard to say, but nonetheless comrades, resisters of a kind, determined to look below the surface of things, determined to find a common ground of humanity, of generosity of spirit. Because one of the things that has always attracted me most about Berger is his generosity of spirit, his humanity. He seems one of the least compromised of writer-artists. He seems to have admirably little to regret. He has not allowed himself to be cheapened. He’s no one’s shill. He seems to stand outside the grubby/glamorous marketing and self-promotion of the literary world and art scene, part of a much older intellectual tradition, somewhat ascetic, monastic even.

If I am perfectly honest, I prefer his earlier work, that which is most informed by a Marxist analysis, whether he is considering the lives of migrant workers, high-bourgeois art and its place in the class system, or the inequity of zoos. It is in those essays that he most approaches the work of Walter Benjamin (one of his heroes) and the kind of engaged, mittel-European intellectualism that flourished between the world wars. (That, I suppose, is the tradition that I have always considered Berger to belong to.) It is here that his ideas seem at their most concrete, their most revolutionary, their most revealing. And his articulation of these ideas matches this – clear, concise, unambiguous: analytical. The less overtly political his work, the more I find it tends to the metaphysical and I find some of his later writings a little precious in places, a little laboured even, as if even he isn’t entirely clear what it is he’s trying to say. (In fairness, I think he says of his own work that at least a third of it could be thrown away without detriment.)

Now would be a marvellous time to reacquaint yourself with Berger, especially if, like me, you have let that relationship cool somewhat. Start with the essays, or the marvellous Into Their Labours trilogy (especially Pig Earth, the first); or the brilliant Success and Failure of Picasso, or the later but quite lovely Here Is Where We Meet, which for my money contains some of his most moving essays, including a beautiful elegy to his mother. But for whatever reason, let’s make this the year we reread some John Berger. Happy Birthday, John Berger.

Alun Severn

November 2016