Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 22 Oct 2016

posted on 22 Oct 2016

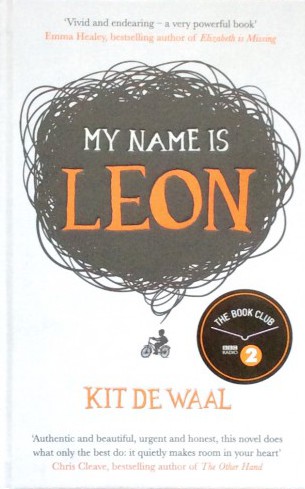

My Name Is Leon by Kit de Waal

This is one of those books that is clearly based on real experience because the characters and the circumstances ring true from the start. I deliberately didn’t look up the author’s background before reading it because I didn’t want it to influence my interpretation of what was going on. Having finished it, I have found out that de Waal was born in Birmingham to an Irish mother, who was a foster carer, and an African-Caribbean father. She also has considerable relevant work experience including working for social services and writing training manuals for white foster carers to help them to meet the needs of black children in care.

The novel is set in the early 1980s and is about many things including the fragility of identity, social injustice and the kindness of strangers. The story is told through the perspective of eight year old Leon, a child with a dual heritage who lives alone with his white mother until she has another child, Jake with a different father who is married, and white. She is clearly a vulnerable woman who has had to cope with severe depression and a drinking problem and soon shows that she is unable to cope with caring for herself or her two young children. Leon takes control and becomes the carer and we learn that he manages his responsibilities extraordinarily well with the demands of feeding, changing and playing with his little baby brother. He is fiercely independent and protective of his family and so is very reluctant to ask for help from Auntie Tina, the friendly neighbour who has been a support in the past. Before long a serious crisis happens which means that social services become involved and the children are taken into foster care.

I found this early section of the story extremely moving and believed in the narrative voice. I loved the tenderness of the opening chapter when he meets his little brother for the first time in the hospital and we have a glimpse of maternal love and protection. The detail about Leon’s increasing anxiety and how this translates into physical discomfort can only have been written by someone who has worked with and observed children in a similar situation. He is a very observant child who gets used to secretly listening and trying to make sense of fragments of overheard conversations. He is also clever at searching through other people’s property and taking things without them noticing. I believed most of this but found that the author over used this as a device to tell us what was really going on. For instance, I didn’t quite believe that he could read and understand the case notes that he found in his Social Worker’s bag.

The children are very fortunate to be taken into the care of Maureen who must be one of the warmest and cuddliest women in literature, she is definitely up there with Pegotty in David Copperfield. Indeed she could be an effective poster girl for foster carers, although I suspect that today she might be criticised for giving her children copious amounts of comforting sugary snacks throughout the day. Although Leon understandably continues to fret about his mother, he and Jake have a pleasant few months being well cared for and loved. Unfortunately everything changes when he realises that the baby is going to be adopted without him. Here de Waal is trying to reflect the real world as she explains in a fascinating interview published in The Guardian:

“Unfortunately, siblings are separated too often. I’ve been on adoption panels, and sometimes there is no other option.”

The despair that Leon experiences when Jake is taken away is heart breaking and although Maureen is very sympathetic and supportive, he is very bewildered. She is completely honest when she explains why it has happened:

‘Because he’s a baby, a white baby. And you’re not. Apparently. Because people are horrible and because life isn’t fair, pigeon. Not fair at all. And if you ask me, it’s plain wrong …’

When the wonderful Maureen is taken into hospital, Leon goes to stay with her sister Sylvia who is a very different mother figure, although kind in her own brusque way. Now he is nine he is allowed to explore the local area on his bike and comes across some allotments where he gets to know a young Rasta known as Tufty and a terse older Irishman, Mr Devlin. Together they could be said to represent father figures who provide many wise words and advice. Through spending time with them he also soaks up information about Irish republican hunger strikes and the current police brutality against black people. Over the weeks Leon becomes interested in helping them with their allotments and with growing things of his own. The metaphor of the garden as a place of hope and renewal for unhappy people is a common one and I would also hazard a guess that de Waal knows something about gardening as there is quite a lot of detail in this section. I liked the way that she builds a picture of a multicultural community that’s rubs along reasonably well until it is disrupted by rumblings of racism outside the allotments that eventually blow up into a full scale riot with plenty of police brutality witnessed by Leon. The author had personal experience of living very near the Handsworth riots in 1981 which presumably informed this vividly drawn section.

I have only focussed on a few of the many memorable moments in this well written debut novel. I personally think that there is far too much content and that the intimate portrait of Leon and his deep sorrow at the loss of his baby brother would have been a sufficiently interesting subject. His desperate attempts to keep in contact with his estranged mother and his developing relationships with both Maureen and Sylvia are beautifully drawn. In my view trying to include commentary about the causes of the race riots seems to be an unnecessary complication.

De Waal is also strongly committed to encouraging others to write about ordinary life and as a result she has set up a fully funded creative writing scholarship at Birbeck, University of London to try to improve working-class representation in the arts. The award is designed to help some of the most marginalised people in society gain access to creative writing opportunities.

De Waal is definitely one to watch and I really look forward to any future novels as her compassionate politics shine through her writing.

Karen Argent

October 2016