Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 12 May 2016

posted on 12 May 2016

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man by James Joyce

For many years I harboured the not very well thought through view that James Joyce’s real achievements began with the short story collection, Dubliners. Certainly, if I had previously attempted to read A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man I had absorbed nothing and had no recollection whatsoever of the book.

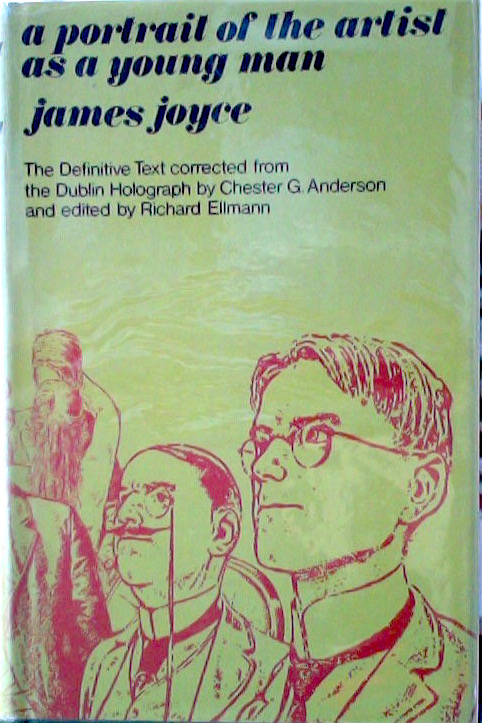

So last week I finally made myself sit down with the beautiful Jonathan Cape ‘definitive’ edition of Portrait, illustrated by the great Robin Jacques. (Cape also publish a similar edition of Dubliners.)

It seemed my ill-informed view was right. I found it a real struggle to get to the end.

Joyce reworked Portrait from his earliest novel, Stephen Hero, working on the new version on and off for ten years, from 1904 to 1914. It is where we first see Joyce testing stream-of-consciousness and the other modernist techniques that would make his reputation and change literature profoundly, influencing Virginia Woolf, Eliot, Beckett, Faulkner, Svevo, and even later and more conservative writers, such as John Updike, who makes absolutely masterful and utterly convincing use of the technique in his Rabbit quartet.

Perhaps the flaws in Portrait are attributable to the circumstances of its creation. It reads like a book that has been laboured over for too long – laboured over until there is no life left in it (or at least, no life left in parts of it).

The modernism seems to sit uncomfortably alongside the more conventional realist elements and rather than enhancing the book diminishes it. One feels distanced from what is being described. Perhaps this is deliberate and Joyce is distancing himself from the painful family circumstances that deeply inform the book – the declining fortunes of a middle class family, his father’s bankruptcy – as well as from his own personal failings, his sexual guilt, his sense of profound alienation, Ireland’s suffocating theocracy, the shame of colonialism.

There are of course memorable scenes in the early parts of the book – incidents at Clongowes college and later at Belvedere; the Christmas meal ruined by a family argument about Parnell and the primacy of the Church; father and son travelling to Cork for the bankruptcy auction – and in these the language and the Dublin idioms are vibrant and crackling with life. But life seems to drain out of the book as it progresses and I must say that in its final stages reading was a chore rather than a pleasure.

Interestingly, Portrait’s two most frequently quoted passages – Dedalus’s famous lines about “silence, exile, and cunning” and his intention “to forge in the smithy of my soul the uncreated conscience of my race” – which are now widely taken to be Joyce’s personal credo, occur right at the very end of the book and within a page or two of each other. I reached them with some relief because they do much to confirm the gravity of the book and the profundity of its undertaking. But it seemed a long wait.

Perhaps, if I manage to read Portrait again over the next ten or fifteen years I will feel differently and see it for the masterpiece it is widely considered to be. But for the moment, it seems a significant but not entirely successful record of a writer who is trying to find his voice and style while also escaping the nation, class and Church that are stifling him.

For my money Dubliners remains an infinitely better and more memorable book and is the early Joyce that I’m sure I’ll continue to return to again and again.

If you don’t have a copy of Portrait and you want one, then do try and find this illustrated edition. Dare I say that if Joyce’s novel had been more like Robin Jacques’ drawings it would have been an unqualified success?

Alun Severn

May 2016