Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 26 Apr 2016

posted on 26 Apr 2016

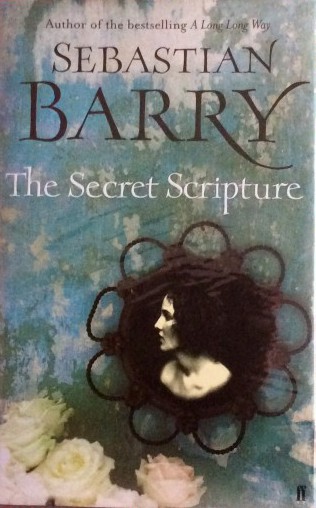

The Secret Scripture by Sebastian Barry

I belong to a book club where members choose a book that they like for us all to read and discuss. Over the years I have sometimes struggled with other people's choices that are not at all to my taste and often put off reading until the last possible moment, a bit like avoiding homework. This was my initial feeling about The Secret Scripture which has been lying unopened on my bedside table for several weeks because I wasn't looking forward to what I thought would be another depressing read about a tragic life. I seem to have read a lot of such stories recently and feel their cumulative oppressive weight. But the time has come to tackle it as the April club looms in a couple of days. What a pleasant surprise to find that once I started reading, I was completely entranced. How could I not have read this fabulous author before? Looking at the fly leaf of the book I see that he has written several award winning novels and yet he wasn't even on my radar!

And yes, it is a truly terrible tale of loss and despair that is an example of thousands of untold stories of people who have been locked away in asylums. The action takes place in Sligo, Ireland which is interestingly described by Barry as a country part fairy tale part madhouse. The poetry of the writing is sublime and is part of what makes it such a memorable book.

The fashion for ‘care in the community’ in the 1970s meant that, as in England, the huge old asylums build in the nineteenth century to incarcarate the mad, bad and sad in society were deemed to be inappropriate places for vulnerable people to live in. As part of this change in attitudes, Dr Grene, the chief psychiatrist at the Sligo asylum splendidly described with ‘his long whitening beard, was sharp as an iron axe. It was very hedge like, saint like,' needs to assess the future housing needs of his remaining patients by investigating their various histories. The woman at the heart of this story, Roseanne McNulty is the oldest of ' fifty ancient women in the central block, so old that age has become something eternal. Continuous, so bedridden and encrusted with sores that to move them would be a sort of violation.'

It soon becomes clear to the reader that Roseanne is the embodiment of a ‘cailleach’ translated as 'The old crone of stories’ and is keeping as secret journal hidden beneath the floorboards in her room because she has learnt the value of silence and secrecy during the decades that she has lived in institutions. Through her sometimes very confused memories we have glimpses of a happy childhood, her relationship with her adored father set against the trials of living with her beautiful but obviously deranged mother from England, who is also eventually sectioned into an asylum.

There are so many episodes in this novel that shined for me that it is difficult to pick my favourites. For instance, who could not be moved by the affectionate description of her as a child playing the piano in the tiny cottage, with her father singing Neapolitan opera as he rests his hand on his cherished motorbike that is also kept in the living room to prevent it going rusty.I loved her keen memory of what it felt like to be fourteen and starting to grow into a woman, becoming dimly aware of boys and spending hours trying to get her hair to curl. This period of indulgent self- regard is interrupted by terrible circumstances leading to her father falling out of favour with the priest, thus being sacked from his job as gravedigger and condemned to instead to be a rat catcher whereby he ' lost something of himself.' Her strange dreamlike memory of helping him with an experiment using feathers and hammers being dropped from a high tower reads rather like a fairy tale. A later scene where Roseanne comes across a bereft mother searching for her lost child at the seashore is searing tragedy of the highest order, I was almost in tears at the sense of loss and panic painted.

As we slowly learn more about her history, Doctor Grene is in parallel struggling to make sense of the very limited official records and is at the same time also coping with his own personal tragedy. His wife of many years is terminally ill and their relationship has clearly become very distant. He sadly reflects that they had used to drink coffee together but recently she has become distant, sleeps apart from him in a separate room and her nightly ritual is to drink Complan, ‘a nightmare drink that tastes of death’ – what a fabulous metaphor for a stale marriage and impending old age.

There are many other memorable and disturbing characters in the story including the mysterious and uncomely John Kane who has worked in the asylum for decades. Roseanne’s husband Tom and his mother, the frighteningly powerful and cruel matriarch both play a significant role in her downfall. And who could not despise the wicked behaviour of Father Gaunt who represents the absolute power and lack of compassion that defined established religion in Ireland at the time.

This is a finely crafted story where two versions of the same history collide, overlap, contradict and connect with a rather surprising resolution at the end. Although it is a cruel tale based on research into real lives, including someone in the author’s own family, it is redeemed by many moments of deep happiness along the way. I am so glad that it was recommended as a book club read and I have already started reading another which promises to be just as good.

Karen Argent

April 2016