Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 04 Mar 2016

posted on 04 Mar 2016

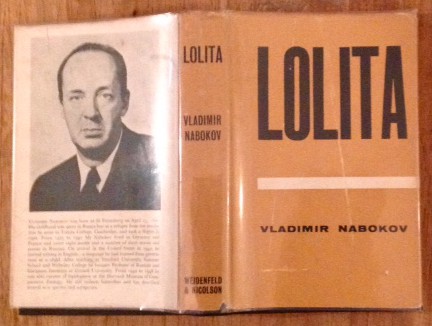

Reconsidering Nabokov’s Lolita

I am generally resistant to the idea that contemporary events “date” novels and make them unreadable, but recently I tried to read Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita for the second or third time – failing yet again – and felt forced to reconsider this view.

Lolita – the story of Humbert Humbert, professor of literature, cultivated European and paedophile, and his “nymphet”, the 12 year-old Lolita – was first published in 1955 as a two-volume paperback by the Olympia Press, home to highbrow “outsider” literature (Genet, Burroughs, Cocteau) and low-end pornography. Sometimes the two were synonymous and Olympia Press published low-end porn by highbrow writers. In such instances, the Olympia Press found its ideal.

But this was not the case with Lolita. Although it was extensively banned and didn’t see publication in the UK until 1959, Nabokov’s novel is not pornography. Whatever Nabokov’s intentions were – and they are still hotly debated – they were higher than that. My own take, for what it’s worth, has always been that Lolita is a transgressive and contrarian joke, designed to disturb. A pompous, self-justifying, unreliable narrator – Humbert – in papers “leaked” by his defence lawyer, makes a lengthy attempt to set the record straight and explain how he became what he is. He does this mainly as an act of self-justification, but also partly for the jury that will try him for murder. (But note that it isn’t Lolita who is murdered: Humbert, we are meant to understand, is not that kind of paedophile.)

The moral fulcrum of the story and its triumph – at least to its admirers – is that readers come to feel some empathy for Humbert, are persuaded of his “victimhood” and even perhaps end up more or less on his side. The US critic Lionel Trilling said: “We find ourselves the more shocked when we realise that, in the course of reading the novel, we have come virtually to condone the violation it presents…”

If only. Lolita fails not because it is too shocking or too “challenging”; it fails because it is for the most part shockingly tedious and over-written. (We must also recognise, however, that Nabokov is “playing” us: Humbert is meant to be a pompous nonentity swollen with his own sense of ego, so just how much of this tedium is Humbert and how much is Nabokov we cannot be sure. That too is part of the joke.)

If tedium and over-writing were the novel’s only failures then Lolita would barely be worth discussing. But there is a much bigger problem: Lolita now reads like a disastrous failure of imagination.

Nabokov imagined paedophilia in the context of a morally ambiguous, transgressive “romance” that would challenge the intellectual preconceptions and ethical judgements of its readers.

The problem is that after Savile and Rotherham grooming gang and a decade of high profile prosecutions the last thing we need is an imaginary paedophilia – especially one that comes dressed as high European culture. Lolita has been rendered obsolete, outstripped at every turn by the enormity of a reality it could not bear to imagine. A salutary reminder that contemporary events do have the power to change not just how we read a novel, but also what we think the novel is capable of.

Alun Severn

March 2016