Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 07 Dec 2020

posted on 07 Dec 2020

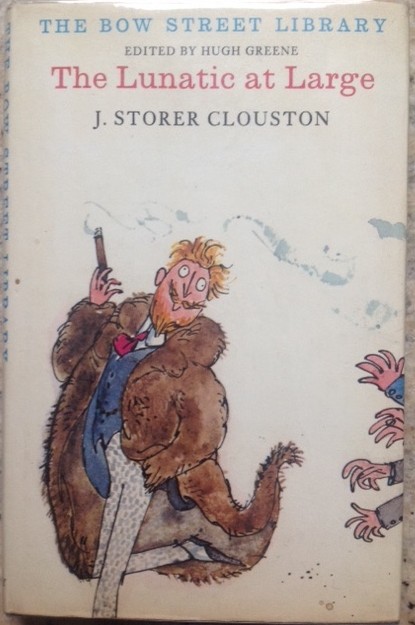

The Lunatic at Large by J Storer Clouston

(Joe) Clouston (1870 – 1944) was the son of a clinical psychiatrist and part of a long linage that had its roots in Orkney – the place he returned to after his education in Edinburgh and Oxford. Although he trained as a solicitor, he never practiced law preferring instead to pursue a career as a writer. Erin Clouston (remarkably no relation) contributing to the blog site, Writing The North, says of Joe’s output:

“As prolific in theme as he was in output, Joe dashed off war yarns, science fiction, Viking sagas, historical romances, social satires, innumerable magazine articles, at least three plays, 62 archaeological papers and a rollicking History of Orkney. He once crafted ten who-dunnits in a fortnight.”

But his most famous, well-regarded and lasting contribution to literature was his ‘Lunatic’ series - satires on Edwardian life in a style that has shades of both Jerome K Jerome and George and Weedon Grossmith. His writing was greatly admired by the young P.G. Wodehouse and there are clear echoes of that anarchic spirit in the work of both of men.

The first of this signature series, The Lunatic at Large, sets up the basic proposition of a ‘escaped lunatic’ at large in society and intent on demonstrating the absurdities of late Victorian and early Edwardian conventions and mores. In this first adventure our anti-hero, Mr Frances Beveridge finds himself a benefactor in the form of a German aristocrat – Baron von Blitzenberg - who is at leisure to explore London and whatever other delights of the UK he can. This is, of course, the cue for lots of terrible linguistic jokes all built on the misunderstandings and ambiguities of a thick German accent. In the book’s introduction, written by Hugh Greene, he notes:

“The comic potentialities of English spoken with a German accent have seldom been better exploited.”

This is definitely a comic frame of mind that was congenial to a certain type of Edwardian comic author but now, frankly, it all seems just a bit wearisome when it is drawn out over such an extended period – as it is in this particular instance.

I much preferred the more devilish and disruptive Beveridge over the essentially decent but rather bumptious Baron. Beveridge is the kind of man who would take something apart just to see how it works but not have any intension of putting it back together. He pushes people from their comfortable perch just for the hell of it.

And so while it’s a moderately diverting romp, the book shows just how hard it is for humour to travel through time successfully. Unlike tragedy that has a timeless universality to it, comedy is a more idiosyncratic commodity and if you don’t laugh at the joke it’s hard to understand why everyone else does. In the end I felt much as I do when I read old snippets from Punch magazine and I can’t escape the feeling that you probably had to be there to understand why it was deemed so uproariously funny or scandalously outré.

I do, however, want to put in a word for the wonderful jacket design in this reprint from the Bodley Head which was published in 1974 in their ‘Bow Street Library’ series. The artwork was by a, then, much less famous, Quentin Blake and is worth the purchase price in its own right.

Terry Potter

December 2020