Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 16 Apr 2018

posted on 16 Apr 2018

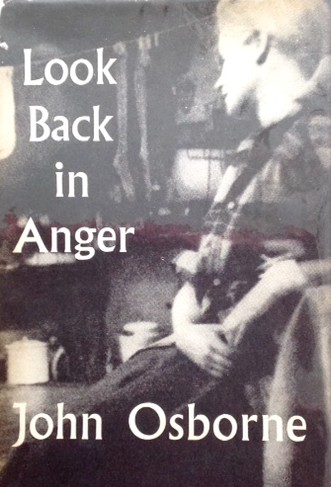

Look Back In Anger by John Osborne

I have seen two or three productions of Osborne’s iconic play – by professional and amateur companies – and I’ve always come away feeling like I’ve had a pretty ambiguous experience. At one level it’s undeniably visceral but it’s also one of those plays that leaves you in a troubled state and I’ve always felt deeply uneasy about the messages Osborne has loaded into his drama.

However, I’ve never read the play until now and I’m conscious that I’ve come to it at a time when Osborne’s reputation as a misanthrope, a misogynist and an all-round unpleasant character is both well established and well evidenced. It’s impossible to come to a script like this without being aware of both its literary standing and the questionable regard in which its author is now held and both of these factors were always lurking not too far in the back of my mind as I read it.

It is, of course, undeniable that Look Back In Anger landed in the world of theatre and drama like something from another dimension. In a world dominated by the likes of Noel Coward, Terence Rattigan or Christopher Fry, this raw, angry, violent and class conscious piece of work must have looked like an alien gate crasher. And Osborne was so clearly enjoying his self-styled role as the scourge of the terribly nice and the understated that he seems to acknowledge no boundaries – there’s nothing that can’t be said, nothing too disrespectful or hurtful.

The play is extraordinarily claustrophobic and takes place in a Midlands bedsit that seems to crackle with the electricity that emanates from Osborne’s mouthpiece for all this discontent, Jimmy Porter. Dan Rebellato, writing for the British Library website provides a useful and concise summary of the spare plot:

“The play centres on Jimmy Porter, an articulate malcontent, living with his upper-class wife, Alison, and their friend Cliff. Jimmy spends his time berating the world and his wife, so to speak, trying to provoke a reaction from the stoical Alison. When eventually she is goaded beyond endurance and leaves, Jimmy begins an affair with her friend, though that too descends into cruel mutual loathing. When Alison returns, having suffered a miscarriage, she and Jimmy begin a tentative, broken reconciliation.”

Osborne uses the character of Porter to try and distil that critical moment in history when the old values of Britain and Empire are no longer to be seen as necessarily desirable or admirable. Porter seems to signal the changing of the guard – the assumption that decent, educated people would grow up to respect the old values of the class system and Empire are going, if not already gone, and the younger generation held back and frustrated by all this will now express their anger and demand their own time.

But that freedom hasn’t quite arrived yet for Jimmy, he’s reduced to taking out his vitriol on those closest to him and his anger manifests itself in ways we’d now typify as classic domestic abuse.

Being able to express so vividly this undertow of anger and frustration led to Osborne being seen as the leading light in a loose coalition of writers who were all, in very different ways, exploring similar themes around the attempts of the younger generation to break the bonds of the past. The publicist for The Court Theatre, George Fearon, coined the phrase ‘Angry Young Men’ (AYM) and it’s a tag line that has stuck ever since.

As it has been pointed out on many occasions, AYM is a largely meaningless collective name but its use does help to highlight an important issue in respect of Look Back In Anger. Just what is Jimmy Porter’s anger all about?

For me, this is where the play becomes especially troublesome. Jimmy’s anger isn’t the anger of the ideologue or even the frustrated armchair politician. He has no allegiances, he postulates no future, his anger is undifferentiated. In truth Jimmy is a cross between a pub bore and a wife-abusing bully – a description that could very easily fit John Osborne himself as he became an increasingly vile human being.

The play is packed full of the most regressive gender politics and capitalises on stereotypes of the violent but creative man who is, because of his violence, devilishly attractive to women. By contrast the women are either victims or vixens and always in thrall to a man. Porter is, in many ways, just a suburban bed-sit fantasy of the disaffected rebel, the Marlon Brando or James Dean’s bad-boy, a bit of dangerous rough for posh girls to flirt with.

Rather than mould breaking the play seems now to look like an excuse for the most unpleasant manifestations of violence towards and against women.

I know that reading play scripts isn’t everyone’s cup of tea but I like it – although I used to do it more than I do now. What it does allow you to do is to not only recreate the drama in your own imagination but to spend time with the words rather than hear them slip past you. I can’t pretend reading Look Back In Anger was a particularly pleasant experience but it was one that made me think about the issues in a way the productions I’d seen previously didn’t.

Terry Potter

April 2018