Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 19 Feb 2018

posted on 19 Feb 2018

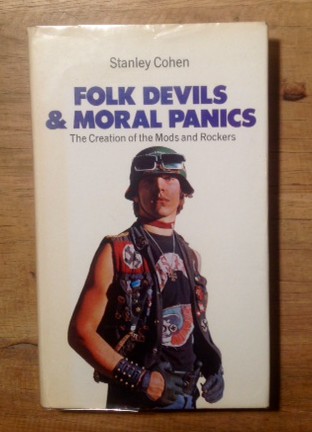

Folk Devils and Moral Panics by Stanley Cohen

There can’t be too many classic sociology and criminology books that coin a phrase that not only passes into common usage but also defines the intellectual territory in quite the way that Stanley Cohen’s 1972 publication has done. Since its original release it has had two or three updates but with or without the new material it is a book that every time you read it remains depressingly relevant.

The notion that society will always cast one group or another as its folk devils – outlaws who threaten the values and stability of the established order – was the motivation for South African sociologist Stanley Cohen to undertake a study of the youth phenomenon of Mods and Rockers and the sort of media, political and public response to what was seen as an unprecedented threat to the fabric of decent society. Of course, what Cohen discovered was that far from being unprecedented, folk devils are always being created to help explain away perceived shortcomings in the functioning of the social order.

The process of demonising counter-cultural groups is what he calls the creation of a moral panic. It’s not actually a term that he devised himself but one which his criminologist colleague, Jock Young had first used. But the way in which Cohen used it projected it into the public imagination.

So how does this notion of a moral panic operate?

- First the media identifies the ‘folk devil’.

- Then it creates stereotypes and/or exaggerates the threat or menace posed by this demonised group.

- This prompts the ‘respectable’ spokespersons or moral entrepreneurs to publically condemn the group.

- Policy makers then respond to the supposed threat with a crack-down.

- The result is the creation of what becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Cohen saw the late 50s newspaper coverage of the Teddy Boy phenomenon and the early 60s media coverage of Mods and Rockers as part of the classic development of folk devils. He follows that through by looking for evidence that the behaviour was as reported on the front pages and found that in reality there was very little to support the level of public outrage the media was able to generate.

In fact, he discovered that the lurid newspaper reporting actually solidified and encouraged the outsider group – giving them a sense of common identity and a perverse sense of purpose. Not surprisingly, more violence followed and the folk devil status of these groups was confirmed in the public mind.

Cohen is also interested in the way in which these moral panics enable the creation of a reactive authoritarianism – a set of ideas that has quite a lot of currency in today’s political climate and the debate about so-called ‘fake’ news. Moral panics are based on exaggeration at best and lies at worst but they have the power of creating deep-rooted public belief in the existence of a real problem despite the absence of any real evidence to confirm it. This fuels a public demand for action and allows legislators to introduce measures that crack-down on the perceived or fictitious message.

The job I do has led me to read the book, either completely or in parts, several times over the past decade and I always find something that echoes the current socio-political situation we find ourselves in.

It’s simply indispensable.

Terry Potter

February 2018