Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 19 Jul 2016

posted on 19 Jul 2016

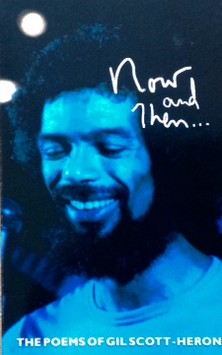

Now and Then by Gil Scott-Heron

Unbelievably, it’s been a little over five years since the untimely death of musician and poet Gil Scott-Heron. Although his career had its ups and downs, there are a couple of things that remained constant – he was effortlessly cool and his influence of contemporary black music was transformative. Scott-Heron can claim to be one of the pioneers of what became the global phenomenon we know as rap and he never lost his passion for the creative fusion of jazz, blues and funk but it is also the case that he was a troubled soul who had to battle his own self-destructive demons.

One of the most compelling aspects of Scott-Heron’s work for me was his overt engagement with the politics of black consciousness and the civil rights movement - although he was also an advocate for social justice on a much wider front. His music always acknowledged its heritage and antecedents and he explicitly labelled himself a ‘bluesologist’ to recognise the debt he owed. However, when it came to lyrics he was a poet and a very fine one at that. When he first began releasing albums in the mid-1970s he was part of a relatively small set of musicians that were exploring the interface between poetry, political discourse and street-based musical improvisation to accompany and ‘sweeten’ the hard political edge. Poems like ‘The Revolution Will Not Be Televised’ and ‘Whitey On The Moon’ became instant classics of their type and show the influence of other artists in the same genre – especially The Last Poets who prefer a very stripped down and minimal musical backdrop to their messages.

The angry, rhythmical delivery of these early poems becomes, over time, tempered by his evolving musical sophistication and collaborations with musicians like the flautist, Brian Jackson, whose playing gives a more wistful, keening edge to the words. One of my particular favourites from that period is Winter in America - a genuinely chilling commentary on the US zeitgeist as it entered the Regan era. And Scott-Heron also reminds us that the unfettered capitalism Regan so espoused can also lead us to the brink of disaster. In We Almost Lost Detroit, which deals with the Three Mile Island catastrophe, the madness that is nuclear power is exposed and the hubris of the human race over its belief in the ability to control this power source is there for all to see in the later Chernobyl meltdown. In fact, he captures the whole Regan era as something of a bad dream – a ‘B’ movie as he calls it. The ‘Movie’ poems are placed early in this collection and rightly so because they capture so much of what Scott-Heron stood for and believed in. Part One of ‘B’ Movie begins with an admonition we’d do well to remember today:

“ The first thing I want to say is, ‘mandate my ass!’

Because it seems as though we’ve been convinced that 26% of the registered voters, not even 26% of the American People, but 26% of the registered voters form a mandate, or a landslide.”

Perceptively, Scott-Heron strips down and analyses how an idiot like Regan could rise to power ( are you listening Donald Trump?)

“ America wants Nostalgia. They want to go back as far as they can, even if it turns out to be last week. Not to face now or the future, but to face backwards. And yesterday was the time of our cinema heroes riding to the rescue at the last minute; the day of the man on the white horse in the white hat, coming to save America at the last moment. Someone always came to save America at the last moment.

And when America found itself having a hard time facing the future they looked to one of their heroes. Someone like John Wayne. But unfortunately John Wayne was no longer available, so they settled for Ronald the Raygun.”

Scott-Heron also had his problems with drugs but despite his own addictions he campaigned long and hard with his anti-substance messages. These were not in the style of the ‘Just Say No’ campaigns – what he believed was that substances were being made available to enslave black people and keep them in a state of subservience. Angel Dust considers the highly addictive impact of PCP and sketches out the ‘dead end street’ in which there’s ‘no turning back’ and, possibly his most commercially successful record, The Bottle, looks at the issue of alcoholism as a form of escape from reality.

There is a tender side to the poet too and in his love song to jazz – Lady Day and John Coltrane – he kicks back and considers how this music can save your soul. In Lovely Day he considers the healing nature of feeling the sun on the back of your neck and how problems are banished by something as simple as a lovely day. This almost mellow tone turns contemplative in his last published material which appears on an album called I’m New Here that was released just before his death. In this we hear Scott-Heron as socially committed and aware as ever but also reflecting back on a life shaped by his mother and the strong women who implanted the values he lived by. So it is fitting that this collection begins with the poem that also heads-up the last recorded work – Coming From A Broken Home. In this poem he tackles the issue of role models and confronts the notion that young black men must have positive male influences in order to flourish. His home was a home made strong by women and the fact that this poem will stand as his final words on those people that created him as an artist would, no doubt, have been a cause of great satisfaction.

“ I come from WHAT THEY CALL A BROKEN HOME,

but if they ever really called at our house

they would have known how wrong they were.

We were working on lives

and our homes and dealing with what we had,

not what we didn’t have.

My life has been guided by women

but because of them I am a Man.

God bless you, Mama. And thank you.”

Terry Potter

July 2016