Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 03 Jun 2016

posted on 03 Jun 2016

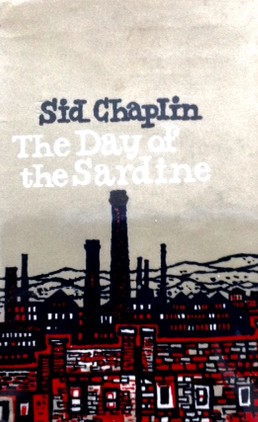

The Day of the Sardine by Sid Chaplin

Sid Chaplin (1916 – 1986) is a real working class son of the North East and was a pioneer of what is sometimes called proletarian literature. What this means in reality is that he belonged to the working class and wrote about them from the inside rather than as a middle class onlooker.

The Day of the Sardine was published in 1961 and chronicles the teenage of Arthur Haggerston as he makes the transition from childhood to the world of work. What makes the book really interesting is the time it was written in – Arthur is what we’d now recognise as a classic teenage rebel. He lives at home, his father has long gone, he’s used to ruling the roost and resents the lodger, Harry, courting his mother, he’s having an affair with an older woman, Stella, and his loyalties lie with a gang that’s constantly at war with rival teens.

But more importantly, Arthur isn’t stupid. He rejects the notion that he has to conform and should be grateful for a steady job in the sardine factory and wants something more – although he doesn’t really know what. He’s dissatisfied with everything – his attitude recalls the anti-establishment stance of Brando in The Wild One – and Arthur will probably rebel against anything you’ve got. But, deep down, he craves a kind of security he’ll probably never get.

To working class kids like Arthur street friendships are everything – and Arthur is loyal to the maximum degree even when experience and common sense tells him he will be let down. However, he knows corruption when he sees it and danger when it calls – his moral compass might be misdirected but there’s nothing wrong with how it functions.

Arthur’s loyalty is stretched to its limits when his best friend, Nosey, gets him into a scrape that might lead him to being arrested for assault and, to compound the problem, he witnesses Nosey’s brother commit murder. All this pressure leads him to take off on the run and there is an extended episode of his rough travels on the lam. Ultimately, he returns home to discover the police aren’t on his tail and that against his expectation Harry comes through for him.

Arthur’s search for meaning in life leads him to flirt with religion – but ultimately he realises that his only real interest in that lay around his sexual interest in the preacher’s daughter and when she gives herself to Nosey he realises that this fascination has also ended for him.

The book ends with Arthur taking a job in the sardine factory and with money in his pocket he reassesses his life – whatever he had is gone but he has money, youth and an open mind. Life lies ahead of him:

“Brother, sometimes I feel that if some character walked up to me and gave me the nod I’d follow on. And never mind the suitcase with the spare shirt and socks.”

Chaplin’s writing is engaging and accessible – he tells the story with empathy, pace and a real understanding of the community he is writing about. Arthur belongs to the same generation as the (more middle class) Angry Young men and to the working class world of Arthur Seaton and Smith created by Alan Sillitoe where rebellion seems a way of taking control.

The book was out of print for some time but it has recently been reprinted. Paperback copies are easy enough to get hold of for well under £10.

Terry Potter

June 2016