Inspiring Older Readers

posted on 28 Apr 2016

posted on 28 Apr 2016

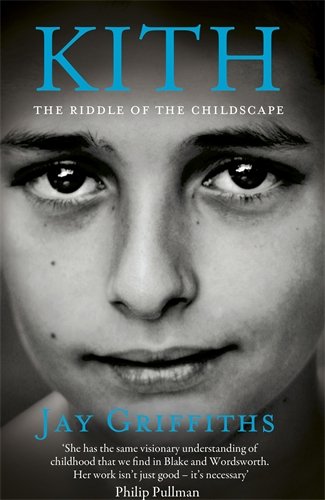

Kith: The Riddle of the Childscape by Jay Griffiths

Occasionally there are books which you feel obliged to read for professional reasons but which break the bounds of the mundane and manage to speak to a wider audience than the select few academics that would usually pick up a book about the changing nature of childhood.

Kith is one of these. Originally published in 2013 it sets itself the task of asking why, in a late capitalist society where material needs are potentially better met than ever before, so many children in the UK say they are unhappy. This is not, of course, new territory. In the past writers like Neil Postman ( The Disappearance of Childhood) have written about the increasing sense of alienation children suffer from in a world of new technology and Sue Palmer’s Toxic Childhood enjoyed a brief period of notoriety when that came out. Palmer’s contention that we have created an essentially toxic environment for our children and that we will reap the whirlwind was absurdly apocalyptic and overstated and, more annoyingly, poorly evidenced and argued.

Griffiths avoids these pitfalls and, although she has a tendency towards the sentimental, she acknowledges that the world of childhood is a complex and multi-faceted thing. Her starting point is the word ‘Kith’ which she argues has lost its true meaning in modern day parlance where we only normally hear it linked with the word ‘kin’. However, she argues the word kith has an important meaning because it was originally meant to represent that space or sphere of influence a child might feel is home territory – and this is what she feels may be under threat.

So the focus of her attention is the way we seem to have traded off the freedom to explore the environment against greater access to technologically advanced material treasures. She uses examples from the past and from other cultures to help explain how modern childhood becomes impoverished through this process. I also think it’s useful that she takes time to challenge some of the general hysteria that surrounds child safety and the threats of paedophilia or ‘stranger danger’. The evidence is pretty clear that the chief threat to children’s safety comes from inside the family rather than from the outside and the statistics and research clearly show that the external threat to child safety is no greater now than it ever has been.

It is also admirable that she raises the debate on the increasing medicalisation of children’s behaviour and the risks inherent in creating a generation of children who carry a ‘diagnosis’ to explain their otherwise pretty normal childhood characteristics – children can be fidgety and lack concentration and be bored without it being pathologised. Middle class parental desire to have a diagnosis for, rather than an explanation of, their child’s behaviour is in danger of creating its own industry.

That’s not to say all is well with this book. Her writing style can be irritating when she flirts with what can only be called the mythologisation of childhood. Although she would probably deny this, it seems clear to me that she has an almost Platonic idea of the perfect form childhood should take and that real childhood can be measured against this in some way. I was also struck by the way in which children aren’t themselves seen as having any agency in this debate – childhood is done to them and they don’t seem to have any say or role in the co-production of that childhood. This is something that seems to me to be highly unlikely. Some discussion about the autonomy we should expect of children in terms of decision making about the nature of the childhood they experience would make a valuable addition. Let me give you an example. I hated most things sporty and games-based at school – it was a part of the timetable I thought was just there to humiliate me and divert me from doing things I was more interested in. In these situations I most certainly didn’t want to be forced to ‘experience’ nature and I most certainly didn’t care about the health rewards of exercise. What’s the legitimate position we should take on this: should I have been given agency to decline the offer of sport and games or should I have been forced into it because older and wiser people than me know what’s best for me? Ultimately, I don’t think Griffiths helps us too much in coming to that decision.

This is a book I’d recommend to anyone interested in the nature of childhood and the kind of childhood we’re creating for the next generation. It is accessibly written for a lay audience and it is most certainly thought-provoking – which are two good ticks on anyone’s checklist of a good read.

Terry Potter

April 2016